In an interview from his remote village in Tanzania, Kansas City native and self-exiled founder of the Kansas City Chapter of the Black Panthers, Lindsey “Pete” O’Neal, says he regrets some of the actions for which he's been vilified and feared.

Fifty years ago, on the day of Martin Luther King Jr.'s funeral in Atlanta, students at Kansas City's mostly black Central, Lincoln and Manual high schools bolted from their buildings after the district refused to cancel classes.

For the next several days, hundreds of local and state police officers, with backup from the National Guard, clashed with a small percentage of Kansas City's black community and some civil rights leaders. By the end of the uprising, six black people had died and the city had tallied millions of dollars in property damage.

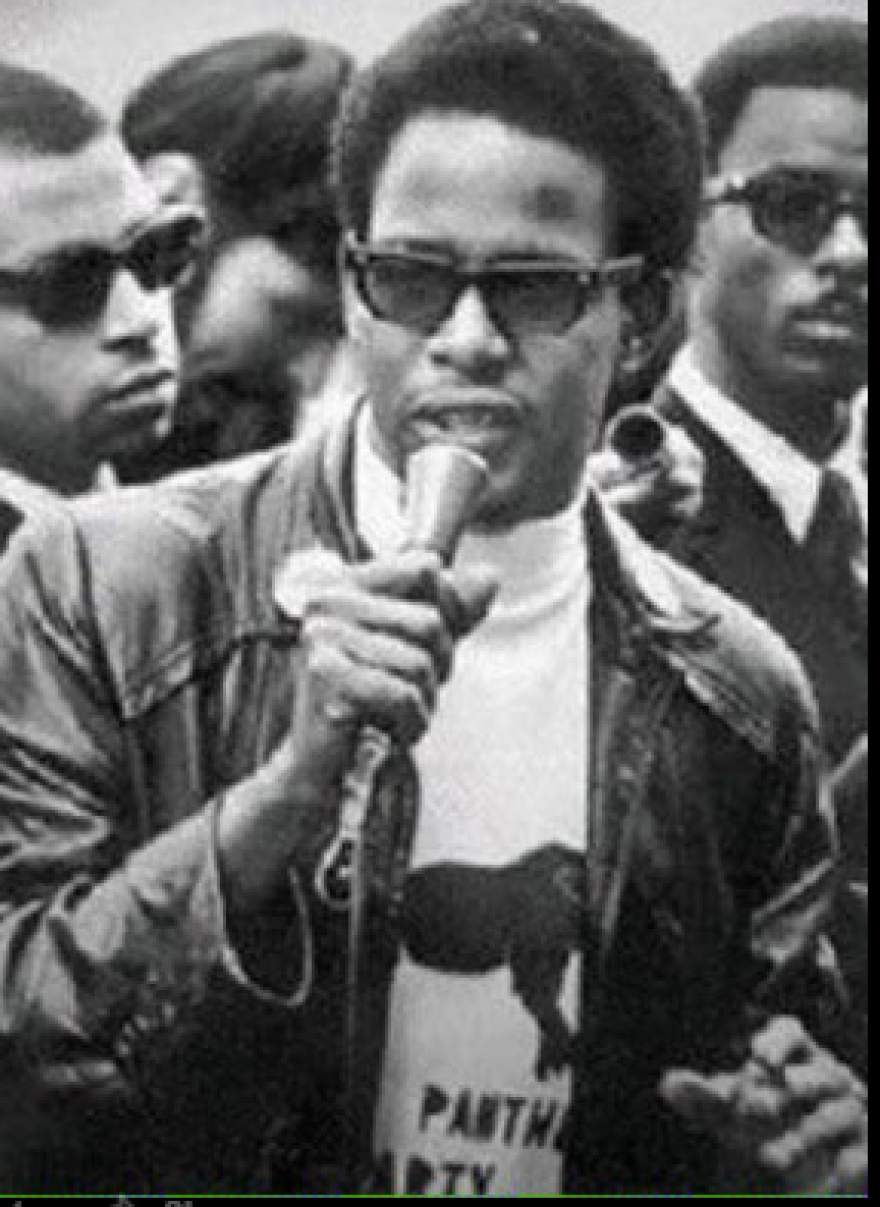

The next year, O’Neal founded the Kansas City Chapter of the Black Panthers. He was later convicted of carrying a gun across the state line and sentenced to four years in federal prison. He still claims he's innocent and says the charge was politically motivated. Certain he'd be killed in prison, if not before he got there, he fled the country and has never returned to the United States.

Today, O'Neal is 77 years old. He says he appreciates how dramatically King changed the course of history, but says he still can not embrace a philosophy of non-violence.

"While I can, at this point in my life, respect the contributions made by those that believed in and practiced non-violence, it was not then, and it is not now, for me," O'Neal says. "If a people are oppressed and if they have no other alternatives, they can resort to violence to correct those wrongs."

Regrets

O'Neal says he's sorry for some of the damage he did during his angriest years.

“I made horrendous mistakes, horrendous mistakes, and some embarrass me to this day,” he says.

He says he still holds no affection for police and feels fundamentally “at war” with a power structure that he believes still holds back the black community.

“I consider myself, old man though I am, a soldier. And if you’re going to participate in war, you participate in an honorable manner. (For example), you do not make light of anyone’s death.”

In 1970, during the height of his activism as a Black Panther, O'Neal wrote in a Panther publication that he was glad a police officer had been killed in the line of duty.

Another thing he regrets: The day that he and his comrades disrupted and tore down the American flag during a service at the Linwood United Methodist Church. He says they were angry that the affluent white worshipers had left the community when black people moved in but continued to come back to worship on Sundays.

“Our position was, if you’re gonna be in our community, if you’re gonna be here with this beautiful building surrounded by poverty, you should support our community,” he says. “They did not agree with that.”

Today, O’Neal is a leader in the small Tanzanian village of Imbaseni, near Arusha. He’s raising and providing an education for 21 adopted African children and runs the United African Alliance Community Center.

O'Neal's third cousin, Rep. Emanuel Cleaver, has been unsuccessfully seeking a pardon for O'Neal since the 1990s.

When O'Neal's mother died recently in Kansas City, Cleaver arranged to have O'Neal hear the funeral service via Skype from Tanzania.

Laura Ziegler is a community engagement reporter and producer. You can reach her via email at lauraz@kcur.org or via twitter @laurazig.