The streets near downtown Kansas City are still dark and quiet on this Thursday morning, but already a green taxi is idling outside of the City Union Mission’s family shelter.

Cameon Valentine and her son, Nicoli, hustle out of their room shortly after 6 a.m. They’re running a bit behind. “Come on, son!” Valentine says.

Nicoli detours to the refrigerator in the shelter’s common room to grab a water bottle. The front door squeaks as he opens it.

“Bye,” calls his mom. “I love you.”

“Love you too,” Nicoli says, his words nearly lost in the sound of car doors opening and closing. Then he is gone, an early morning cab rider headed for 7th grade classes at his middle school in the North Kansas City School District.

When Valentine lost her rental unit over the summer due to a missed utility bill, she was frantic at the thought that Nicoli and his younger sister, an elementary student, would have to leave the schools where they were happy and secure. Worried about putting them in new places, she entertained the thought of homeschooling.

But staffers at the North Kansas City School District had good news.

“Their schools told me, no, you’re not pulling them out,” Valentine said. “We can have a cab come and get them because technically you don’t have a permanent residence.”

Valentine’s children are among thousands in the Kansas City area who benefit from a federal law, the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act. Signed into law in 1987, it guarantees students the right to an uninterrupted education even if they leave their school’s boundaries to live in a shelter or motel room, or move in with family members.

So every school day, hundreds of cabs and vans crisscross the region, getting kids between home and school and home again. For families, the service is a godsend. For school districts, it’s a mixed blessing.

A growing number of homeless students

McKinney-Vento services cut down on the chaos created by student moves in and out of the classroom during the school year. Multiple studies, both locally and nationally, have shown that children do better if they stay in the same school.

But the McKinney-Vento Act is a mostly unfunded federal mandate. Congress funnels some money through state education departments to award to school districts in the form of grants. But only a small number of districts benefit. Most foot the cost of transportation from their general funds.

As recently as a decade ago, McKinney-Vento services were mostly a footnote for many school districts. But in recent years the numbers of students benefiting from the program have soared.

Kansas City Public Schools led the region with 1,200 students receiving services last year. The Independence School District was close behind with 964. Numbers in Raytown and North Kansas City topped 500. Kansas City Kansas Public Schools served 876 homeless students last year. And the combined number of McKinney-Vento students served by Johnson County’s six school districts has topped 1,000 the last seven school years.

Not all students accepted into their districts’ McKinney-Vento programs need rides. Some still live within their school’s boundaries or get rides from family members. Districts help homeless students in multiple ways, which include providing clothing and personal items, tutoring and waiving ACT test costs and graduation fees.

“We try to do everything we can to make sure that those students’ attendance is not disrupted and they can continue their education,” said Michele Eagle, McKinney-Vento coordinator for the Raytown School District.

The costs

But transit is the biggest expense and the task that keeps district staffers busy.

“We probably right now are cabbing between 55 and 70 students on any given day,” Eagle said. Last year, her district spent nearly $500,000 on transit costs for homeless students.

Jessica Smith, who coordinates McKinney-Vento services for the Kansas City, Kansas Public Schools, puts the number of students getting rides in her district in the hundreds. She uses a private transit service, sending vans around the metro to pick up students.

“I have a kiddo who comes from Lee's Summit,” Smith said. “He's often late because the van will pull up to a home and the if kiddo is not ready, the driver will wait a couple minutes. A couple of minutes at every home can add up to a lot of time. But the kids get to school.”

Some of the increase in McKinney-Vento caseloads is due to schools getting better at identifying homeless students and offering them services. In Raytown, teachers and other staffers watch for students who begin arriving late for class or who get dropped off by car instead of riding the bus, Eagle said.

But in Raytown, like other districts, the rise in transient families has mostly to do with housing.

Raytown is an older community of small homes that get passed around among landlords, Eagle said. Families often get dislocated in the shuffle, even if they’re current on their rent.

“The end result is oftentimes the family has to move,” Eagle said. “But because of the short notice and the lack of available housing in the area, they struggle to find a new permanent housing location, and they find themselves doubling up with a relative, going to a coworker, or staying in a motel.”

Housing is also the major cause of dislocation in better-off suburbs, said Valorie Carson, with United Community Services of Johnson County.

“You have a lot of people who have incomes that are not increasing dramatically, yet the cost of housing continues to go up,” she said.

An absence of family shelters in Johnson County and Wyandotte County worsens the problems. Taxis that collect students from shelters in downtown Missouri often cross the state line to get students to schools in Kansas City, Kan., or the Johnson County districts.

Preventing homelessness

Many districts are looking at ways to prevent families from becoming homeless in the first place. They’re partnering with churches and community groups to help stop an eviction, or counsel a parent about finances.

Kansas City, Kan., Public Schools led the way with Impact Wednesdays, which is now known as Impact KCK. The partnership involves a large church, Avenue of Life, and multiple other ministries and social service groups.

Smith refers families to Avenue of Life, where they have an opportunity to meet with social workers, lawyers, potential employers and others, all gathered at the same place.

“Organizations like Avenue of Life partner with the school district to not only permanently house families, but to teach them how to stay permanently housed. That’s the missing piece,” Smith said.

Johnson County School districts like Shawnee Mission and Olathe have formed similar partnerships, Carson said.

“It’s more cost effective to be able to prevent the experience of homelessness than it is to actually then try to get people back into housing,” she said. “And that's where I think some of the community partnerships become very, very key.”

Homelessness happens, though. Kimberly Clay returned from a stay in the hospital after she suffered a stroke last year to find her belonging and those of her two sons out on the curb. Her landlady in Kansas City, Kan., had evicted them and changed the locks while she had been ill.

Clay sought help at the City Union Mission’s family shelter, where she was accepted into the transitional living program. To her great relief, she learned her two sons, both high school students, could remain at their school in Kansas City, Kan.

“When we lost everything else, they could still hold on to that,” Clay said. “It meant they still had their friends. Their teachers were really supportive. My oldest son got to graduate from his home school and go on to a culinary program so that was great.”

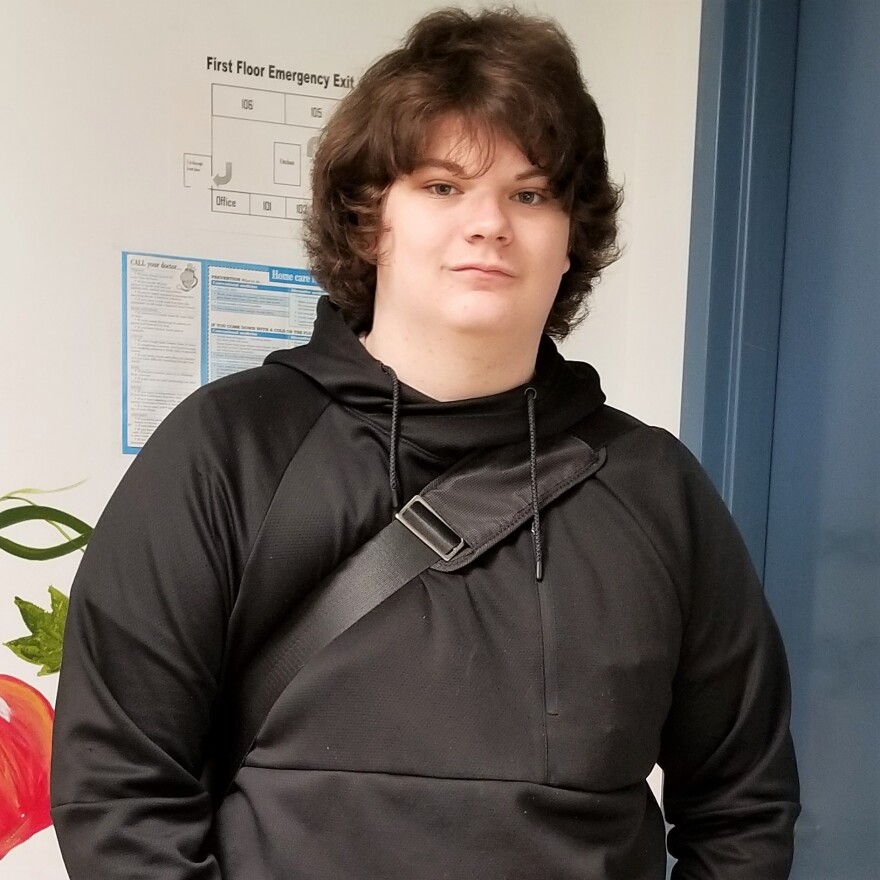

About half an hour after Nicoli Valentine caught his taxi on that recent morning, a white van pulled up in front of the family shelter. Myles Clay was waiting with his fully loaded backpack, braving the morning cold with just a hoodie. His ride to Washington High School, where he is a junior, takes about 20 minutes. After school, he goes to a tech program at Kansas City Kansas Community College. Then the van brings him back to the shelter.

Clay is about to graduate from the City Union Mission’s family program. She’s looking for a job and a place to stay in Kansas City, Kan., so Myles can remain at Washington High.

Whatever the future brings, she’s grateful for those van rides and the McKinney-Vento program.

“It’s been something very positive,” Clay said. “It’s really gone a long way toward helping the kids be more stable in their educations.”

Barbara Shelly is a freelance contributor for KCUR 89.3. You can reach her atbshellykc@gmail.com.