Across the metro, Kansas City schools are serving more students of color, especially Latinos, but that diversity isn’t reflected on school boards.

Without representation, students of color can feel like no one’s looking out for their interests.

Those tensions played out recently in Lee’s Summit, where the all-white school board clashed with the district’s first black superintendent over diversity training. But that’s exactly the kind of training educators need to better serve children of color, said Nate Hogan, a Kansas City Public Schools board member who is black.

“That’s not to say that an all-white school board full of folks who come from higher incomes and stable environments can’t be effective,” Hogan said. “But I do think it would be a lot more difficult for them to have a perspective that aligns with the kids’ perspective without some serious coaching and training and professional development to help them really, truly understand where these kids are coming from.”

KCUR asked school board members for 18 metro-area school districts to self-identify their race and gender; 16 boards responded in full. Of those 112 board members – 58 women and 54 men – 87 identified as white, 22 identified as black or African American, two identified as biracial and one identified as Latino.

Comparing board members’ identities to student demographics in Kansas City-area districts, whites were overrepresented on every board except for Hickman Mills. (Hickman Mills, which is 73.2% black, has seven board members that identify as black or African American.) Besides Lee’s Summit, the school boards for Belton, Blue Valley, Fort Osage, Independence, North Kansas City, Park Hill and Shawnee Mission have all white members.

And Latinos, despite being the fastest growing subgroup in nearly every school district, were hardly represented at all. Kansas City, Kansas, a majority Latino district, has one white board member and five black board members. (There is currently a vacancy on the board. The seat was previously occupied by a black woman.)

On the Missouri side, Manny Abarca is one of the only Latino elected officials at any level of government. He won his seat on the Kansas City Public Schools board in April.

“One of the cultural aspects of our community is that we’re gracious. We’re not going to ask for more than we’re given. I don’t think you’re going to see Latinos taking to the streets and saying, ‘We demand representation,’” Abarca said. “But I think that will happen in the next generation.”

In fact, it’s already starting. The oldest members of Gen Z, born in the late 1990s, are old enough to vote – and many second-generation Latinos are more politically engaged than their immigrant parents.

But they aren’t running for school board, at least not yet. One of the reasons electing representative school boards is a challenge is because the demographics of registered voters don’t match up neatly with the demographics of the school-age population. Overall, nonwhites make up 27.5% of the metro’s population but 36.8% of the population younger than 20.

A changing Kansas City, Kansas

Edgar Palacios is the founder of the Latinx Education Collaborative, a nonprofit that tries to recruit and retain Hispanic teachers to teach in Kansas City-area schools.

“I always get push back. ‘Whoa, you’re trying to segregate the schools. Latino students with Latino teachers.’ No, I’m just advocating for one more in every building,” Palacios said.

To Palacios, the lack of Latino representation on local school boards is glaring. According to the Mid-America Regional Council, the Latino population has grown by 38% in the last decade, and it’s not just the Kansas City, Missouri, and Kansas City, Kansas, public schools that are educating more Latino students. In fact, many of the suburban districts – Belton, Fort Osage, Independence, North Kansas City, Olathe and Shawnee Mission – now educate more Hispanic students than black students.

Lack of legal status doesn’t fully explain why Latinos aren’t getting elected. The share of foreign-born Hispanics has declined every year since 2000, and 90% of U.S. Latinos are citizens.

That means the problem isn’t immigration because most Latinos are able to vote, Palacios said. “But there’s a lack of access to mentors, a lack of access to political networks and a lack of access to financial resources. We don’t see ourselves in those positions. You just don’t feel like you can run.”

Kansas City, Kansas, is a city without a racial majority. In 2018, the city was 38% white, 24% black and 30% Hispanic. The school district has been majority Hispanic for the last several years.

But Kansas City, Kansas, voters have never elected a Latino to the school board.

When Irene Caudillo ran for the Kansas City, Kansas school board in 2015, she didn’t win. But when a board member resigned a month after the election, Caudillo, the executive director for a Latino community services organization, was appointed to that seat. She served for two and a half years and “loved every minute” of it.

“I think Latino families felt more comfortable approaching me because I shared their language and culture,” she said. “And it was comforting for them because of my role with El Centro.”

So in 2017, Caudillo campaigned again, this time to keep her seat.

“As I went knocking on doors, particularly going into the African American community, I met many people who saw this as an African American seat because an African American had held it previously,” Caudillo said.

Caudillo lost again, coming in fourth in an at-large election for three seats.

Demographic shifts in the suburbs

It’s not just the urban districts that are getting more diverse. Increasingly, families of color are leaving the city for well-regarded suburban districts like Lee’s Summit. Lee’s Summit is 85.5% white, but one in four Lee’s Summit students are children of color. There’s a marked achievement gap between students of color and their white peers, even when controlling for family income.

But when former Superintendent Dennis Carpenter tried to sound the alarm, some white parents – and white board members – balked. Things became contentious between Carpenter and the board after he recommended diversity training for the staff, leading to his eventual resignation.

Eighth grader Mia Myers-Ray was upset that no one left in leadership looked like her.

“I think that the superintendent leaving was definitely a wake-up call for the school district and how they’re making African-Americans feel,” she said. “Somebody that we looked up to is now gone.”

To Mia’s mother, Cortney Ray, Lee’s Summit doesn’t feel as welcoming as it used to. The vitriol toward Carpenter and the equity plan over the past year has been distressing for her family. She worries that with Carpenter gone, the all-white school board won’t look out for students of color, many of whom have reported racist bullying.

“I have two brown children that walk into white schools every day,” Ray said. “I don’t want them to feel like they have to conform to what Lee’s Summit deems acceptable. I want them to be them, and right now, I don’t feel like they can be.”

How school boards are elected

Candidates of color might have a better shot if more school districts elected school boards by subdistrict instead of at-large. KCPS is the only Missouri school district that has subdistrict elections, and it’s also the most diverse in the region, with three white board members, two black board members, one Latino and one white/Latina board member.

Although the KCPS board doesn’t reflect the diversity of the district’s students, 90% of whom are children of color, it gets pretty close to matching the demographics of the city, which in 2018 was 60% white, 28.7% black and 10.2% Latino, per U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

Latinos in Kansas City, Kansas, might have a better shot at representation if school board members were elected by subdistrict like in KCPS, but Kansas leaves it up to local school districts to decide how the school board is elected.

“The statutes date to 1968,” Scott Rothschild, the spokesman for the Kansas Association of School Boards, wrote in an email. “That year may be relevant because it is right after a big wave of school consolidation of school districts in Kansas ... (and in) those communities where there were two or three different towns, they all wanted to make sure they had at least two board members.”

Blue Valley and Olathe elect six of their seven board members by subdistrict, and Shawnee Mission elects five of its seven board members by high school attendance area. But all seven members of the Kansas City, Kansas, school board are elected at-large.

“At-large elections have been challenged for quite a long time under the federal Voting Rights Act,” said Morgan Kousser, a professor at the California Institute of Technology who has served as an expert witness in many voting rights cases. “With at-large elections, it’s difficult for minority voters to elect candidates of their choice.”

The demographic shift currently underway in Kansas and Missouri was happening in California in 2001 when lawmakers passed the California Voting Rights Act, which prohibited at-large elections anytime it would impair the ability of a protected class to influence the outcome of an election. Today, 54% of school-age Californians are Latino, and nearly 200 school districts have switched from at-large to subdistrict elections.

“It's had a dramatic effect,” Kousser said. “It's about 60% more Latinos on boards that switched versus only 15% more in areas that were at-large and stayed at-large.”

Kousser said it doesn’t matter if a board starts out majority white or majority black. The people in power don’t want to give it up.

Caudillo doesn’t plan to run for school board in Kansas City, Kansas, again. But she said going from at-large elections to subdistrict elections would make it easier for Latinos to win elections.

Getting candidates of color to run

But subdistricts alone won’t guarantee representation. Proponents for more diverse governing bodies say districts need to do more to encourage people of color to run.

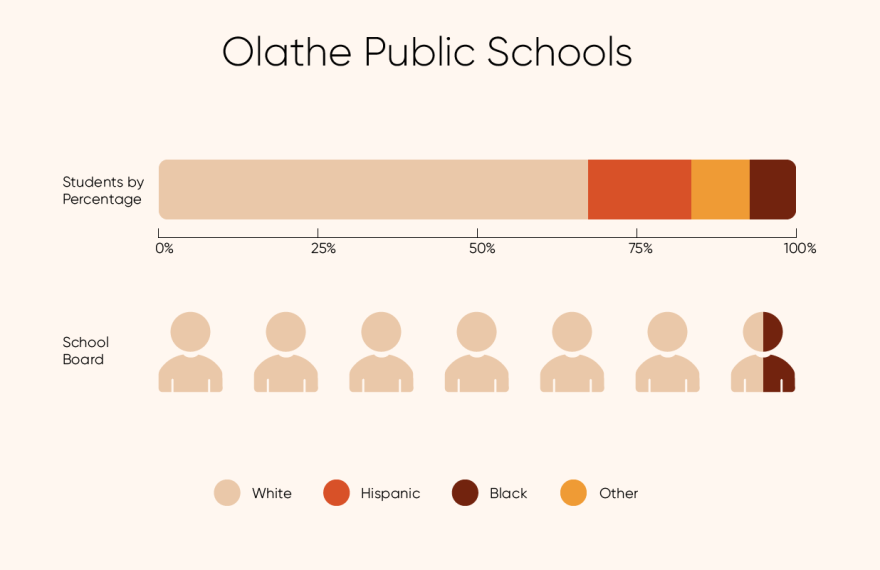

Shannon Wickliffe, who is biracial (white/African American), has served on the Olathe School board since 2015. He said growing up there he didn’t have many teachers who looked like him.

“My family moved here when I was in the fifth grade, and I think that I had one teacher of color,” said Wickliffe. “So I think I can lend a voice to what it would mean to see – and what it does mean – for our students to see people that look like them that they can identify with.”

Before running for school board, Wickliffe served on various nonprofit boards in Olathe, including the Olathe Public Schools Foundation, which supports the school district through fundraising.

“I sort of see nonprofit boards as a stepping stone,” Wickliffe said. “You start serving on the board of a local charity, you get to know people, and that’s where someone said to me, ‘Hey, have you ever thought about doing this?’”

Wickliffe said there are ways to recruit candidates of color who would be good school board members, like asking them to serve on advisory committees. For instance, he was invited to be part of the bond task force to build Olathe West, which convinced him he’d like being on the school board.

That’s exactly what Rev. Darron Edwards, a black minister whose wife teaches in Lee’s Summit, is talking about when he says school districts need to be more intentional about inviting communities of color to participate.

“You have to say, ‘Hey, we see the discrepancies, we see the problems that we have, we see the glaring misfortune that is caused by not having representation in the halls of power,’” Edwards said.

It has been a year of trepidation for the Lee’s Summit congregants at Edwards’ United Believers Community Church. He said black parents want a more representative school board, but no one is ready to announce a run.

“In an affluent district like Lee’s Summit, it takes money to run,” Edwards said. “It takes capital to do the things that need to be done. And that handicaps people of color because whatever they can raise, somebody else can raise five times the amount. That’s five times the name recognition when people get to the polling box.”

The next Lee’s Summit school board election isn’t until April 2020, when voters will also weigh in on a no-tax-increase bond issue. On the Kansas side, many school board seats will be up for grabs sooner, this coming November. Candidates already had to file to run for those seats.

No one filed to run against Wickliffe, so he’ll keep his seat on the Olathe school board. And though he thinks more could be done to recruit candidates of color to run, he also doesn’t want to put anyone in a box because of their race or ethnicity. To him, that’s like trying to bubble in a form with limited options.

“Even now when I’m asked for racial or ethnic data, I’ve gotten really good at filling in ‘other,’ when there is an ‘other’ category. I love it when it’s ‘circle all that apply,’” said Wickliffe. “Maybe that seems like a silly thing, but as we have more students who are living this experience, we need to not run away from it.”

Methodology

Through administrative assistants and public information officers, KCUR asked school board members from 18 metro-area school districts to self-identify their race and gender. Districts don’t necessarily collect this information, and Grain Valley declined to do so on KCUR’s behalf. Liberty provided information for four of its seven board members, which was enough for KCUR to confirm that the board isn’t all white. The full data set, which is current as of Sept. 8, 2019, is available here:

School boards represented in the photo illustration at the top of the post, left column, from top to bottom: Belton, Blue Springs, Blue Valley, Center, Fort Osage, Grain Valley, Grandview, Hickman Mills and Independence. Right column, from top to bottom: Kansas City, Kansas; Kansas City, Missouri; Lee's Summit, Liberty, North Kansas City, Olathe, Park Hill, Raytown and Shawnee Mission.

Editor’s note, 9/26/19: This story was updated to include the resignation of Brenda Jones from the Kansas City, Kansas, Public Schools board earlier this month.

Editor's note, 10/1/19: This story was updated with the correct demographic information for the Blue Valley school district. Blue Valley is 73.1% white, 3.2% black, 5.6% Latino and 18.1% other.

Elle Moxley covers education for KCUR. You can reach her on Twitter @ellemoxley.