For science educators, the COVID-19 pandemic is the ultimate teachable moment.

That’s why a small team of teachers working with the University of Missouri is already developing a coronavirus curriculum and teaching it to high schoolers around the state. And there are plans to get these lessons into even more classrooms this fall, when kids will hopefully be back in actual classrooms.

“I think it's really difficult for teenagers,” said Pat Friedrichsen, a professor of science education at MU. “They're very social. They want to be with their friends. And so we wanted them to understand why this policy is going to help us flatten the curve.”

For several years now, Friedrichsen has been working to encourage science educators to teach about relevant, real world problems. She’s helped teachers tackle issues like vaping and genetically modified foods.

Now, with a $200,000 grant from the National Science Foundation, she is helping create a coronavirus curriculum in the middle of a pandemic, and that work has taken on new urgency.

‘Unprecedented opportunity’

Raytown High School science teacher Christy Darter had just finished teaching a unit on viruses when COVID-19 closed schools in March.

She was especially worried about her graduating seniors.

“It was hard not to be able to see them and talk to them when I knew that they were probably upset about something that was very relevant to our class,” Darter said.

Darter wasn’t working with Friedrichsen’s team before the pandemic. But when a colleague invited her to join an online professional development workshop in late march, the MU professor said something that really resonated with Darter.

“Dr. Friedrichsen talked about the fact that she believed in activism through science education,” Darter said, “and I realized this situation that we’re in is an unprecedented opportunity to teach kids a topic that is relevant to their everyday lives.”

Darter set up a Google Form so her students could ask about the coronavirus. They had a lot of questions.

“What is happening? How do I get this? Why is it affecting certain populations of people more than others? How many symptoms do I have to have to get the test? Is there a chance that I can have this and not know it and transmit it to my family?” she recalled them asking.

That’s when Darter knew she had to teach about the pandemic, even as she and her students lived through it.

‘What am I going to do in this pandemic?’

Christine Royce is the retiring president of the National Science Teaching Association and a professor at Shippensburg University in Pennsylvania, where she teaches instructional online technology.

She said over the last decade, there’s been a shift in science education toward helping students make sense of the world around them.

“One of the benefits of science is while we like hands on, we also do a lot with images, videos and pictures,” Royce said. “So while we might not be in a lab physically, a teacher can do video demonstration. They can provide a set of data the students would then use. Students can still engage in that sense-making part.”

Royce said when schools started to close ion order to slow the spread of COVID-19, the Foundation put together a collection of virtual resources for educators who wanted to teach their students about the coronavirus right away.

For elementary students, that might look like “asking students to make observations about people going out and staying socially distant or wearing masks,” Royce said. “Then it gets into how you catch a cold, which is a virus.”

Older students can get into the biology of the disease. Royce said there are some engaging virtual simulations out there showing how quickly viruses can spread.

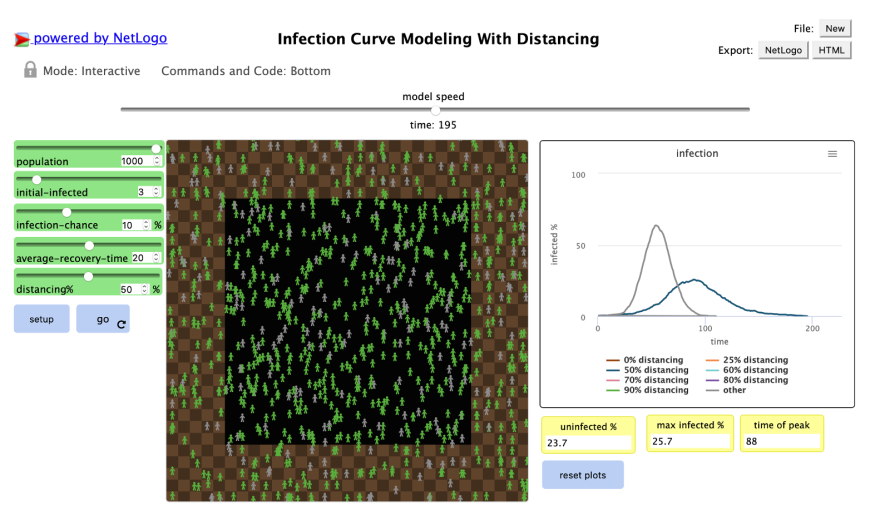

Friedrichsen’s team of teachers at MU has put together a lesson using one of those modeling tools.

“Let’s say 20% of your population is physically distancing,” Friedrichsen said. “What does that do to your infection curve versus if 80% of people do this?”

At Rockbridge High School in Columbia, science teacher Andrew Kinslow is using the COVID-19 lessons in his aptly named Contemporary Issues in Science and Society class that he co-teaches with a social studies teacher.

“I particularly talked about what flattening the curve actually means, illustrating St. Louis in 1918 as a result of the influenza outbreak versus Philadelphia,” Kinslow said.

Back then, St. Louis had fewer deaths than Philadelphia because it shut down sooner.

“In our framework, we have a component at the end where students make decisions,” Friedrichsen said. “In this case, it's a personal decision: ‘What am I going to do in this pandemic?’”

More harm than good?

Before the pandemic, a big part of Kinslow’s job was teaching media literacy to his science students.

“Helping students ask a few key questions. Who is the author of this piece of information and who is it intended for? Is this a purely informational piece put out in more of a scientific article? Is this satire? Is this clickbait?”

He says those skills are especially useful now.

“We really want students to think about how you can be a part of the spread of misinformation, much like the COVID virus, if you don’t take time to really critically evaluate and think about where this information is coming from,” Kinslow said.

At the very beginning of the project, the MU team brought in a child psychologist to make sure that teaching about a pandemic during a pandemic wouldn’t be causing more harm.

“When it became apparent that we were going virtual and had families in all kinds of different situations, that question came up,” Kinslow said. “The advice we received was that if we are flexible in meeting students where they’re at, providing some good exercises for them to do would be really helpful.”

Darter, the Raytown teacher, said learning about the coronavirus together is helping her and her students alike process difficult emotions. She says her students’ lives have been upended by the pandemic — some are watching younger siblings, working jobs at businesses that are still open and helping support their families.

Still, she says they’re managing to log in to learn about the coronavirus.

“I do have a large number of students right now who are working very long hours at grocery stores, hardware stores, Walmart,” Darter said. “I thought participation would decline very dramatically, and it has not declined.”

It turns out students want to learn about the pandemic disrupting their lives and education.