Trees are among humans’ most sacred relatives, said Alex Villalobos-McAnderson, a Shawnee-based energy medicine practitioner.

Villalobos-McAnderson noted that connections to the earth run deep, even amid the turbulence of modern life and political uncertainty.

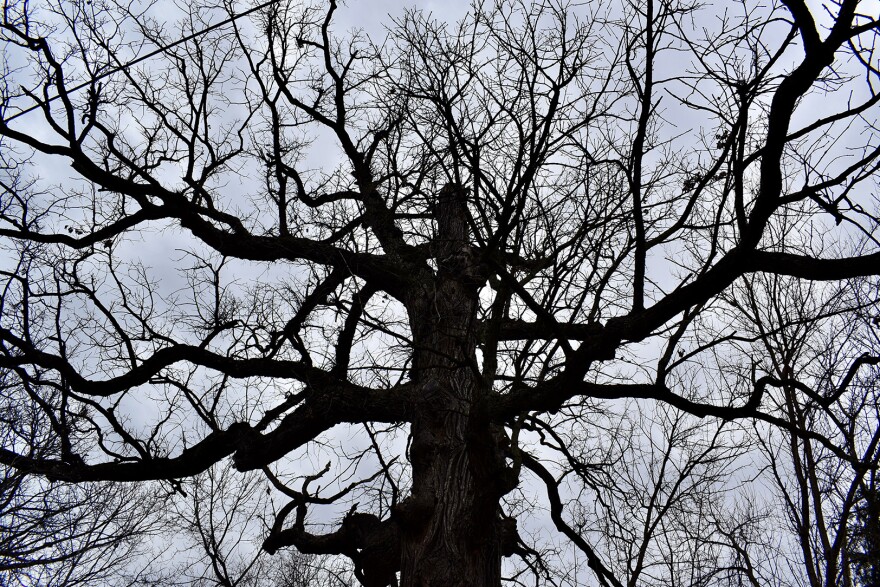

A 250-year-old oak tree in Kansas City’s historic Northeast was declared a “Liberty Tree” in 1976 by the Missouri Department of Conservation and State Revolution Bicentennial Commission. But it is set to be cut down in January because of fungal root disease.

The tree doesn’t know that it’s the busy holiday season or that a vast cultural divide has manifested in America, said Villalobos-McAnderson, owner of Villalobos Vitality.

“In a time where so much feels fractured, rushed, and disconnected, ceremony creates a pause,” she said of rites offered by Indigenous people to honor life. “It invites us to slow down, to listen, and to be present.”

Celebrating the tree, a “200-year-old living monument to our nation’s history, is about thanking it for the energy it has contributed, said Villalobos-McAnderson.

“Trees give endlessly — oxygen, shelter, medicine, shade, and balance — yet as a society, we have grown disconnected from the land and from the relationships that sustain us,” she explained. “Ceremony in moments like this is an act of remembrance, reciprocity and resistance. It brings hope — not just for me, but for the community.”

With permission from the property owner, Villalobos-McAnderson recently visited the residential backyard on Monroe Street that’s home to “Grandfather Tree” with her friend Ivan Ramirez. The two gave offerings, sent prayers, and endeavored to simply be present with the tree while it still stands.

“I wanted to touch his bark, to acknowledge his life, and to honor all that he has witnessed: generations of people, seasons, storms, resilience, and change,” she said. “Ceremony allows us to slow down and say, this life mattered.”

“There was powerful symbolism in this moment,” Villalobos-McAnderson added. “A sentient being called Liberty, who has weathered centuries of change, now standing at the edge of transition during a time when so much in our political and social systems feels uncertain and strained. That resonance was impossible to ignore. But we know death is not the end — it is a transition.”

Ramirez initially alerted Villalobos-McAnderson to the tree and its fate after seeing a news story about neighbors gathering to toast the tree and its long life earlier this month. Holding ceremony for the centuries-old tree was another way it needed to be honored, she observed.

“Ceremony is one of the oldest technologies we have for healing, remembering, and coming back into right relationship — with ourselves, with each other, and with the land,” Villalobos-McAnderson explained. “Long before systems, institutions, or titles, our ancestors gathered in ceremony to process grief, mark transitions, offer prayers, and restore balance.”

“Indigenous people are still here,” she added. “We are still tending to the land. We are still honoring our relatives. And we will continue to be here — always.”

This story was originally published by Startland News, a fellow member of the KC Media Collective.