For more stories like this one, subscribe to A People's History of Kansas City on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or Stitcher.

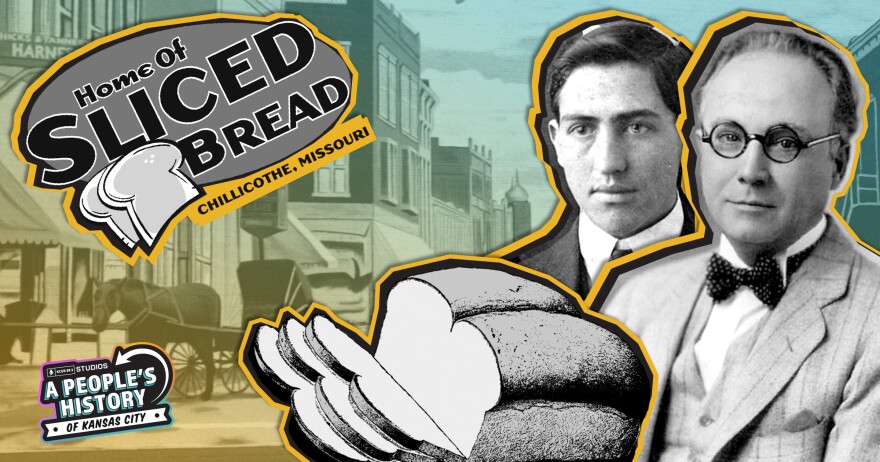

On the main strip of town in Chillicothe, Missouri, you’ll pass by a large colorful mural: “Home of sliced bread.”

It’s actually the official slogan for the town, which hosts an annual Sliced Bread Day on July 7, a celebration made official by the Missouri General Assembly in 2018.

As part of the festivities, there’s a parade, concerts, a 5K run, a golf tournament and a bread baking competition. Thousands of people come out every year to this rural town of about 10,000 people.

But according to former reporter Catherine Strotz Ripley, less than two decades ago, residents of Chillicothe had no idea they even had this claim to fame.

“I don’t know how everybody pretty much forgot about it,” Ripley says.

Up in flames

For most of history, if you wanted a slice of bread, you had to take a knife and cut it yourself. The slices wouldn’t be a uniform width or shape, and sometimes might get smushed in the process.

It was Otto Rohwedder, a jeweler from Davenport, Iowa, who came up with the idea for a machine that could quickly create a perfect set of slices from a bread loaf. By 1917, his bread slicing machine was ready for production: a 10-foot-long metal box with a row of sharp blades, pulsating up and down and side to side.

Ripley says that Rohwedder’s invention was all ready to be manufactured at a plant in Illinois when the factory was destroyed in a fire.

“He lost everything,” she says. “All of his design plans, his equipment, everything. And so he just kind of gave up.”

Rohwedder soon fell ill, and his doctor told him he didn’t have long to live. So he sold his jewelry business and went all in on building another bread slicing machine.

But he had a hard time finding anybody who would actually want to use it.

“Bakers scoffed at the idea,” says Ripley.

Luckily, Rohwedder reconnected with an old friend, a fellow inventor and entrepreneur named Frank Bench, who happened to run a bakery in Chillicothe, Missouri. The two had previously worked together on a bread display rack.

Bench agreed to give the machine a shot. They put an ad out in the paper: “The greatest forward step in the baking industry since bread was wrapped — a fine loaf sold a better way.”

The ad went on: "The idea of sliced bread may be startling to some people. Certainly it represents a definite departure from the usual manner of supplying the consumer with bakers loaves. As one considers this new service one cannot help but be won over to a realization of the fact that here indeed is a type of service which is sound, sensible and in every way a progressive refinement in Bakers bread service."

The next day, on July 7, 1928, sliced bread from Rohwedder’s machine was made available to the world for the first time.

Within two weeks, Ripley says the amount of bread Bench’s bakery sold went up 2,000%. “And bakers were really knocking down his door,” she says.

‘Morale and saneness’

Rohwedder’s innovation couldn’t have come at a more perfect time: the culmination of nearly 50 years of rapid industrialization, when more and more manufactured products were geared towards ease and convenience.

Uniformed sliced bread helped boost the sales of the dual-sided pop-up automatic toaster, which was first patented in 1921. And in 1930, Continental Baking Company — one of the first bakeries to produce fortified bread — introduced Wonder Bread, a manufactured, pre-sliced loaf now widely available to the public.

Within a decade, and despite the twin financial pressures of the Great Depression and World War II, sliced bread quickly became a staple in American households.

So much so, in fact, that the U.S. government’s brief attempt to un-slice bread was met with a furious backlash. On January 18, 1943, new regulations set by the Office of Price Administration banned bakeries from selling pre-sliced bread in an attempt to help keep prices low for the war effort.

Following the ban, a woman named Sue Forrester sent a letter to The New York Times on behalf of the nation’s housewives: "I should like to let you know how important sliced bread is to the morale and saneness of a household," she wrote.

Forester complained of having to hand cut over 30 slices of bread a day to feed her family, calling it a waste of time, energy and money. “They look less appetizing than the baker’s neat, even pieces.”

And because of the war, a good bread knife was hard to find.

According to a Mental Floss article written about the incident, the rule was apparently so disliked that nobody in the government wanted to confess to having had the original idea. It didn’t take long for the ban to be overturned.

On March 9, 1943, The New York Times reported this headline: “Sliced Bread Put Back on Sale; Housewives’ Thumbs Safe Again.”

A forgotten success

Sliced bread wasn’t just a success, it was a revolution. Yet neither of the original men who made it possible got rich off it, and the town of Chillicothe forgot about the central role it played.

Bench lost his bakery during the Great Depression, while Rohwedder sold his patent rights to the Micro Westco Company and joined their Bakery Machine Division, which they named after him.

Despite a diagnosis that only gave Rohwedder a few years to live, he ended up surviving for decades longer, passing away in 1960 at the age of 80.

It was almost by accident that Rohwedder’s legacy started to emerge, nearly four decades after his death.

While researching for a history book project, Catherine Stortz Ripley — then the editor for The Chillicothe Constitution Tribune — spent a lot of time looking through the library’s microfilms of old local newspapers. Among the tens of thousands of clips she scrolled through, one story stood out immediately.

“It was just a small headline,” Ripley recalled. “It said: ‘Sliced bread is made here. Chillicothe Baking Co. the first bakers in the world to sell this product to the public.’”

Ripley remained skeptical of the claim, but found it interesting enough that she copied the article and wrote a little blurb about it for the Constitution Tribune. Eventually, she published the finding in her book, “Dateline Livingston County: A Look At Local History,” which came out in 2001.

Two years later, a reporter from The Kansas City Star took interest in Ripley’s rediscovery and interviewed her for an article on the invention’s anniversary: “At 75, Sliced Bread Deserves A Birthday Toast.”

That’s when things really began to pick up steam. The Star article was picked up by the Associated Press and shared across the world.

“I was getting calls from even Australia and Canada and major news markets… and they were wanting to know the rest of the story,” Ripley says. “And unfortunately, all I had was that newspaper article.”

A little sleuthing and a lucky tip finally led Ripley to someone who could fill in the rest of the story: Richard Rohwedder, the son of Otto, who had been living in Arkansas and kept a scrapbook full of materials that told his father’s journey.

In fact, Richard was actually there in Chillicothe that day in 1928 at the Chillicothe Baking Company — a young boy watching his father's machine make its grand debut.

Livingston County commissioner Ed Douglas immediately realized how sliced bread could become an economic opportunity for Chillicothe — and a way for residents to rally together and be proud of their town.

“I mean this is something we can really build on,” says Douglas, who now goes by the nickname “Sliced Ed.”

“Everyone knows the saying, the greatest thing since sliced bread,” Douglas continues. “They don’t say the greatest thing since the iPhone or anything else, they say it’s the greatest thing. So it really is the standard of all innovations past, present and future. And that’s really what made this country great. It’s about entrepreneurship and ideas.”

The Grand River Historical Society Museum in Chillicothe now boasts a bread slicing display where you can see one of Rohwedder’s early machines.

And the town was able to acquire Frank Bench’s old bakery and converted it into a welcome center — you can tell which building it is by the giant loaf of sliced bread on the roof.

“When we first started this 20 years ago, my family said dad you’re embarrassing us. I mean they just thought this is silly,” Douglas says, laughing. “But interestingly enough, they don’t say that anymore. It’s become a big enough deal they say, ‘OK, you’re right.’”

This episode of A People's History of Kansas City was reported and produced by Suzanne Hogan, with editing by Barb Shelly and Gabe Rosenberg and help from Mackenzie Martin.