For more stories like this one, subscribe to A People's History of Kansas City on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court announced a decision in the landmark case, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

Justices unanimously ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, striking down the “separate but equal” doctrine that had ruled the land since the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson U.S. Supreme Court decision.

What a lot of people don’t know, though, is that a Kansas Supreme Court case from Johnson County five years earlier helped lay the groundwork for the historic ruling.

“There’s a direct line that can be traced from that case in South Park, Kansas, to the one in Topeka,” says Kansas City journalist Dan Margolies.

That case, Webb v. School District 90, might never have come about, however, if it hadn’t been for a few determined women, who pushed for equality with everything they had.

The teacher who prized education above all

Corinthian Clay Nutter worked hard to get an education.

Born in 1906 in North Central Texas, she spent more time picking cotton as a kid than going to school.

“My mother could not even read her letters or write her name. There I was, 16, and I had never been inside of a junior high school,” Nutter said shortly before she died in 2004.

“But,” she added, “I was determined to.”

Her dream came to fruition in the early 1920s when she moved to Kansas City, Missouri, at age 16. First, she graduated high school. Then she completed a junior college program at Western University in Kansas City, Kansas.

By the early 1940s, Nutter was teaching at Walker School — a dilapidated two-room elementary school for Black children in South Park, Kansas, an area that is now encompassed by the city of Merriam.

“Whatever was there was broken down,” Nutter said in an interview around 1995. “We just didn’t have anything.”

Walker’s playground equipment consisted of things like a swing set with no swings. The only bathrooms were outside.

Inside, a bare light bulb suspended from the ceiling in the basement illuminated rats scampering around and standing water that would rise as high as three or four feet.

“The air be coming in those windows like you were sitting outdoors… It was horrible as far as my mind is concerned,” remembers Delores Locke-Graves, who was a student at Walker back then.

Around 1946, parents of the Black students started complaining to the all-white school board, asking them to make improvements, to no avail.

The families became particularly frustrated in 1947, when a new elementary school was built three blocks away. While tax dollars from Black families had helped pay for the new school, only white children were allowed to attend.

The new South Park School had nine teachers to Walker’s two teachers. It also — in stark contrast to Walker School — offered kindergarten, had a sizable auditorium and operated a school lunch program.

At its core, this story is about these two schools — and the vast disparity between them.

Before the new school for white children was built, a bond election took place. The Walker parents requested increasing the amount so that their children’s school could also be improved, but the school board denied their requests. All of the $90,000 raised went to the new school.

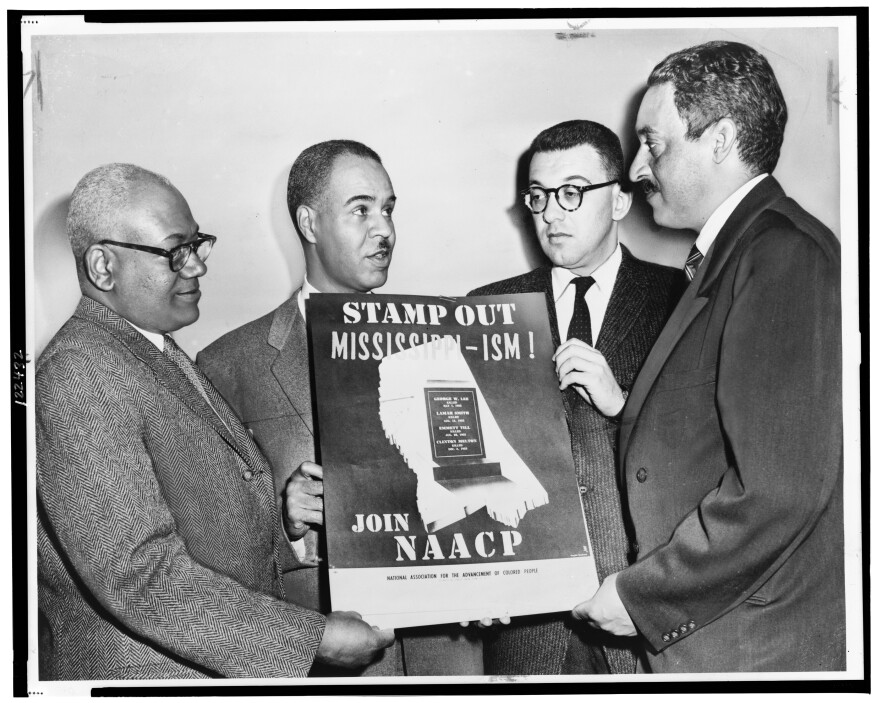

Rather than being discouraged, however, the Walker parents — led by Alfonso and Mary Webb — just got more and more fired up. They hired a lawyer and formed a South Park branch of the NAACP. One of its charter members was Walker’s very own teacher, Corinthian Nutter.

It was a risky move for Nutter.

Across the country, teachers were shying away from anything to do with these types of lawsuits for very real fears of professional repercussions. When schools integrated, non-white teachers were the first to get fired.

Nutter wasn’t immune. After she lobbied the school board for improvements alongside the parents, the board didn't renew her contract.

“I knew I wouldn't have a job, but that was alright. I was trying to help,” she said. “As raggedy and as angry as I was most of the time, I was working for practically nothing in the first place.”

Corinthian Nutter would never teach at Walker School again. But she wasn't done teaching its students.

The radical activist masquerading as a housewife

Born in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1917, Esther Swirk Brown was just a kid when her mother died.

A self-professed “trouble-maker,” she was mostly brought up by her father and uncle, Russian Jewish immigrants involved with radical leftist causes.

“Her orientation was to be concerned about inequality, workers rights, oppression,” says Susan Brown Tucker, Esther’s daughter.

By high school, Esther Brown was picketing for garment workers and spending summers at Commonwealth College in Arkansas, a suspected communist stronghold — dangerous activities during a time when the U.S. government was persecuting communists.

Brown was investigated for suspected communist ties several times, starting in her 20s. No official charges were ever filed, despite an official letter to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover recommending as much.

Eventually, Brown got married and settled in Merriam, Kansas — in a white, middle-class neighborhood south of South Park.

She first heard about the frustrating situation at Walker School from Helen Swann, her Black domestic worker, whose children attended there.

“I said to her, ‘Mrs. Swann, maybe I ought to go to your school board and talk to them. Being white, they'd probably listen to me where they don’t to you,’” Brown recalled on a recorded tape shortly before she died in 1970. “I was aware of racial prejudice.”

After she reached out, the school board invited Brown to speak at an upcoming meeting.

When Brown arrived at the South Park School’s gymnasium, she found an overflowing crowd of 350 agitated white people — including the school board, which Brown described as looking “like a bunch of lynchers from the South.”

Brown got on the podium and tried to make the case for improving Walker School. Before she got a chance to finish, the crowd erupted.

“Everyone began to hoot and holler and jeer,” Brown said later.

“Of course, it was at this point that I realized that this meeting had been called for my benefit to intimidate me… I don’t know if I’ve ever been madder. I only know that I was so angry at the injustice of the whole thing that all I could think was, ‘What am I going to do?’”

Looking around at the pristine gymnasium in the brand-new school and the angry crowd, everything changed for Brown. Her cause was no longer simply about improving Walker School. It was about making sure the Walker kids had everything the white kids had.

“It was at this time that I thought for the first time that those colored kids belong in that white school,” she said. “What I said was, ‘This is wrong and we're going to do something about it. You wait and see.’”

The case against the school board

By this point in the story, Esther Brown and Walker School parents started to realize they had a case — and a good one at that — because the way the school board was operating these two schools was illegal.

First, the vast disparities between the two schools was a violation of the “separate but equal” doctrine that ruled the land. On top of that, Kansas law only permitted segregation by race in elementary schools in cities of more than 15,000 residents.

“Towns like South Park, that city was not allowed to segregate students by race, but nonetheless it did so,” says Margolies.

Margolies, a retired KCUR reporter and editor, is writing a book about Esther Brown with her daughter, Susan Brown Tucker. He says these kinds of laws are what made Kansas — a historically free state — an ideal place for test cases against the “separate but equal” doctrine.

“That’s in contrast, for sure, to the states of the Confederacy, where segregation was universally the norm,” he says.

Realizing a lawsuit was imminent, the South Park school board redefined the boundaries for the South Park and Walker schools in May 1948, gerrymandering the district so that white students were officially a part of the South Park district and Black students were a part of the Walker school district.

“There were white families who lived much closer to the Walker School than the South Park School. There were Negro families who lived closer to the South Park School than the Walker School,” Brown said.

It was the final straw.

Five days later, Webb v. School District 90 was filed in the Kansas Supreme Court, asking for the integration of South Park School. The plaintiffs were three boys and three girls, children of some of the most active NAACP members in the community.

“They thought it would be a matter of weeks, a couple of months at most until the case was resolved,” says Margolies.

But the case stretched on into the summer — greatly testing Esther Brown’s limited patience with lawyers and the general slowness of the law.

“I decided to call the NAACP in New York and inform them of what was going on — or rather, what wasn't going on,” Brown said. “They didn't know me from a hole in the wall.”

People she bothered included Thurgood Marshall, the head of the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund and the U.S. Supreme Court’s future first Black justice.

National NAACP lawyers came to Brown’s aid on several occasions — including the time Marshall called a Kansas NAACP chapter from New York to settle a funding dispute, reportedly bellowing into the phone, “GODDAMNIT, GIVE THAT WHITE LADY THE MONEY.”

“It’s unusual for the NAACP nationally to involve themselves in this kind of a small case, but I was halfway hysterical all the time and wouldn't leave them alone. I guess they had to,” said Brown.

“Her chutzpah is remarkable,” says Margolies. “She could be domineering. She could be condescending, but all in service of this cause, which she was determined to see through to the end.”

A mere two letters into her correspondence with NAACP lawyer Franklin Williams, Brown wrote: “We are going to win this case if it kills me, and then we are going to continue this action throughout the state.”

The Walker Walkouts

When a verdict still hadn’t been reached by the start of the 1948 school year, Brown came up with a plan: “I gathered all the plaintiffs together at a meeting at the Baptist Church and I said, ‘Look, let's not accept this Walker school… Let's hire two teachers and let's teach in two of the homes in South Park… What do you say?’”

The parents knew they had to do something bold to prove to the school board they were serious — so they agreed.

The boycott was as much against the school board as it was the deplorable conditions of the school.

The first person Brown called was teacher Corinthian Nutter, asking if she would teach for $100 a month until the case was won. Despite the obvious professional risks of going against the school board, again, Nutter said yes. So did another teacher, Hazel McCray-Weddington.

“It was a beautiful situation. They provided their living rooms. We fixed it up as near as a classroom as we could,” Nutter said.

Delores Locke-Graves was one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, and she remembers how her mom gave up their living room for the boycott school.

“I thought it was great. My parents were the type of parents who believed in love and taking care and honesty and all this kind of good stuff,” she says.

The 40 or so children who attended the boycott school became known as “the Walker Walkouts.”

Meanwhile, two students began the school year at Walker School, which was staffed with two teachers — both with questionable credentials, according to Corinthian Nutter.

“The school district hoped to sort of wear the parents down by attrition, and they kept that school open in the hope that some of them would relent and give up and eventually send their kids back there,” says Margolies.

To coax parents back to Walker School, the school board offered free lunch, and spread rumors that the boycott school wouldn’t count as an accredited year — which didn’t end up being true, but played on the parents’ worst fears.

When a handful of parents did succumb to the pressure and re-enrolled their students in Walker School, they received prompt communication from Nutter, encouraging them not to surrender to the school board.

The plea worked — some children actually came back to the boycott school.

When pressed in a recorded interview why she put herself out there like that, Nutter said, “Schools shouldn’t be for a color. They should be for children.”

For the people spearheading the charge, the case became unequivocally the most important thing in their lives. The parents held rummage sales and bake sales to fund the lawsuit and teachers’ salaries.

Esther Brown fundraised all over Kansas, making presentations to local NAACP branches, labor unions, and churches.

One night, she even made a pitch on stage at a Billie Holiday concert.

Notably, they did all of this in spite of the danger they were in.

Some people involved in the lawsuit lost their jobs. Others became victims of death threats and violence. More still were denied credit at the local store, which was owned by Virgil Wisecup, the head of the school board.

Delores Locke-Graves remembers walking up to the South Park School one day and hearing Wisecup tell her, “Get your ass away from here.”

“I assumed he was a Ku Klux Klan,” she says.

Locke-Graves says the community banded together. They protected each other and kept each other motivated.

Locke-Graves remembers how her mom used to invite Esther Brown and Corinthian Nutter over when everyone needed a break.

“It was a beautiful sight when you could see those ladies. I was just a girl, but I was watching them, you know. And they would come together and they would have chicken and tea,” she says. “They seemed like they loved one another.”

At times, the boycott was hard to financially and emotionally sustain — but Esther Brown in particular held firm.

“It was like when Esther come around, it was going to be alright,” says Delores Locke-Graves. “Esther Brown was that lady who gave, I would say, the other Black ladies in the community courage to hold your head up. We're going to lick this case. It's going to come to an end.”

‘Victory won by children who went on strike’

Finally, in June 1949, after families boycotted Walker School for an entire school year, the Supreme Court of Kansas ruled that Black students were legally entitled to attend South Park School. About 40 Black students were admitted to the newly built grade school at the start of the following school year.

“And to the credit of the principal of that school, he welcomed them,” says Margolies.

“Victory won by children who went on strike,” the headline of Kansas City's The Call newspaper trumpeted.

It was the first grade school desegregation victory in which the NAACP Legal Defense Fund played a direct role. Thanks to the coverage by Black-owned Kansas newspapers like The Call and the Topeka Plaindealer, South Park became nationally famous.

Delores Locke-Graves was one of the students who integrated South Park School. All of these years later, she’s grateful for the opportunities she got — but it wasn’t easy being one of a few Black students in a sea of white kids.

“It's hard to explain. You're there, but then you're taught to be careful,” she remembers. “The janitors are white. The cafeteria is white. Counselors are white. Everything. They had nothing Black.”

Years later, when Locke-Graves had children of her own, she spent her day off from work volunteering at their mostly white school.

“No one was there for me when I was there, but I got a chance to be there for our Black children,” she says.

After the South Park victory, Corinthian Nutter went on to teach at multiple schools in Olathe, Kansas. By the time she retired in 1972, she had received her master’s degree in education and had risen to the role of principal at Westview Elementary, which was nearly all white.

Esther Brown, meanwhile, was elected to the board of directors of the Kansas NAACP.

“She saw this case in South Park as a springboard for action elsewhere in the state,” Margolies says.

When Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka began materializing, several of the people from the South Park case were tapped to lead the charge, including Thurgood Marshall and lawyer Elisha Scott.

On May 17, 1954, the United States Supreme Court ruled that school segregation violated the U.S. Constitution.

The fact that Esther Brown shares the same name as the iconic legislation is purely coincidental — but she did play a role behind the scenes. Some credit her with convincing Oliver Brown, a Black Topeka minister, to sign on as the lead plaintiff. Others say it was thanks to her tireless fundraising skills over several years that the case was successful.

Whatever it was — when the community in Topeka gathered a few days after the decision to celebrate, Esther stepped up to the podium. “It is the ‘little people’ like us who bring about such things as Monday’s Supreme Court opinion,” she told the crowd. “The most brilliant lawyers couldn’t have succeeded but for the help of people like you here tonight.”

‘It’s not over’

70 years after the Brown v. Board decision, the nation has a long way to go before education is equal for students of all races and incomes.

But Brown remains a milestone achievement, and it likely wouldn’t have played out in the same way if it hadn’t had been for Webb v. School District 90 five years earlier.

You can see the local appreciation all over Johnson County today in exhibits and historical markers.

Delores Locke-Graves says she and the other Walker Walkouts used to have an annual picnic at Brown Memorial Park every summer.

Just this past March, the new Merriam Plaza branch of the Johnson County Library dedicated a meeting room to Alfonso and Mary Webb, community activists who spearheaded the lawsuit and whose late sons were the first two plaintiffs listed.

At the ribbon cutting, their son, Victor Webb, got up to speak, and echoed Esther Brown’s words from 70 years ago, noting the value of all the people who came together to fight the school board.

“Everybody knows about Brown vs. Board of Education. Well, Miss Brown got her start right here in Merriam. She started right here with my dad,” Webb said. “And in this nation that we live in, we need to continue the fight. Because it ain't over.”

This episode of A People's History of Kansas City was reported, produced and mixed by Mackenzie Martin with editing by Barbara Shelly and Suzanne Hogan. Archival interviews of Corinthian Nutter and Esther Brown were provided by Greg Rieke and Susan Brown Tucker.