For more stories like this one, subscribe to A People's History of Kansas City on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or Stitcher.

Most people consider the Stonewall uprising the start of the American gay rights movement. But gay rights groups had already been around for two decades by the time New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn in June 1969 — including here in Kansas City.

What made Stonewall such a turning point? Part of the credit belongs to Kansas City activist Drew Shafer. Powered by a group of determined volunteers and a donated printing press, he helped create a crucial gay rights network in 1966.

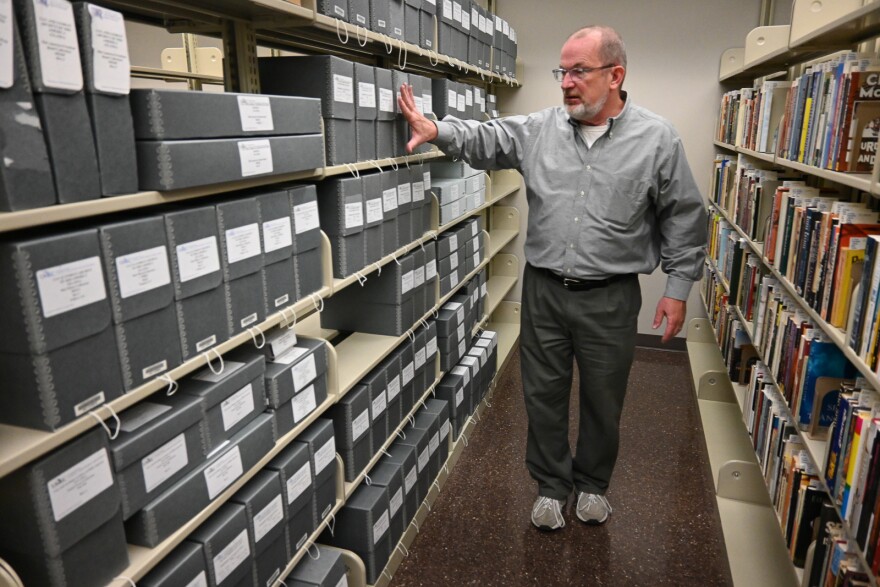

“He was just one of those people who was able to make connections and just take it upon himself in a very Midwestern way to make things happen,” says Stuart Hinds, co-founder of the Gay and Lesbian Archive of Mid-America.

‘Somebody everyone found the ability to connect with’

Drew Shafer was many things in the 1960s. He was optimistic. Handy around the house. The life of every party. And, perhaps most notably, quite the persuasive speaker.

“He found early in life that he was able to get others to see his point of view fairly easily,” according to Mickey Ray, Shafer’s longtime partner.

Openly gay, Shafer gave gay rights speeches at college campuses during a period of rampant LGBTQ discrimination in the United States. Back then, you could be arrested for simply “appearing” gay. Once, Shafer nearly lost his job after acknowledging he was gay on a Kansas City radio show.

Some of the few places Shafer and other LGBTQ folks could really be themselves were Kansas City's gay bars. Located on Troost Avenue between Linwood Boulevard and 34th Street, these establishments were mostly untouched by the police.

“It was very unusual because in big cities — in particular in New York — most of the '60s was a period of increasing oversight and clamp down on activities in bars," Hinds says. "Here, it wasn’t nearly as oppressive."

Ray elaborates on a website largely devoted to writing about Shafer:

“Naturally, Drew was a big part of that scene… There were always after-hour parties at his home and he easily made friends within every spectrum of the gay and lesbian community... He once told me he really just wanted to have a club and have fun.”

Shafer had a happy upbringing, says Ray, which can partly be attributed to his extremely supportive parents. His mother, Phyllis Shafer, was a legendary LGBTQ activist herself and ran a boarding house for Shafer's friends.

“A lot of people had to hide or compartmentalize who they were around loved ones, around work scenarios. And Drew didn't have that,” says historian Kevin Scharlau. “That's part of why I think Drew was able to rise to the level of leader of gay Kansas City politically at that time."

It was this personal freedom, Scharlau believes, that drove Shafer’s interest in pursuing gay and lesbian rights for everyone.The formation of a national network

The 15 or so American gay rights organizations that existed in the mid-1960s called themselves “homophiles” in an attempt to deemphasize the sexual aspect of their identity — but they were far from unified.

In fact, gay and lesbian activists regularly butted heads over how conforming or radical the movement should be.

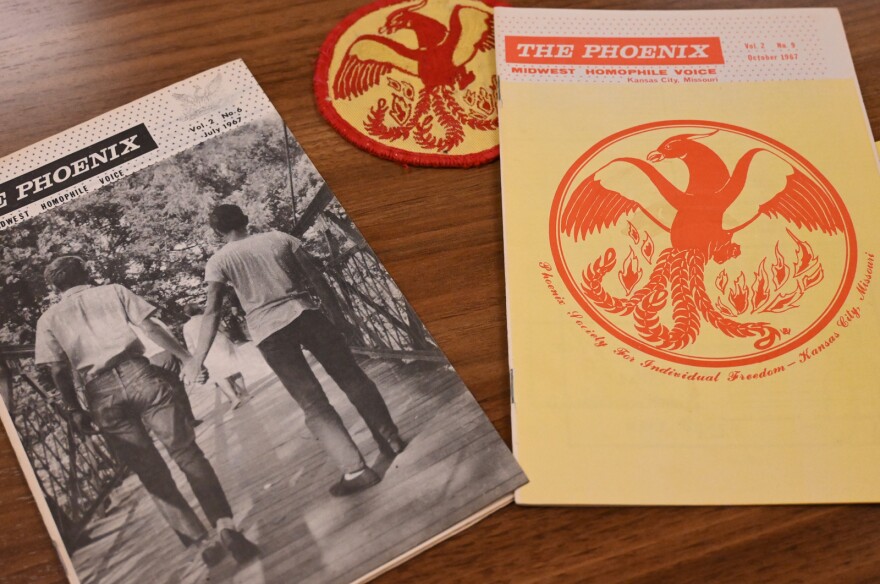

To see the discourse play out in real time, look no further than the LGBTQ magazines they published. That included the Ladder, geared towards lesbians, and ONE, a magazine so “obscene” the U.S. Post Office once refused to deliver it.

“And so it's in the pages of these magazines that debates within the community start to take place,” says Hinds. “But by the mid-1960s, despite their best efforts, they’re not making a huge amount of progress.”

In February 1966, the leaders of these groups finally decided to get together in person for the first time. Hesitant to give any specific group (or coast) a leg up, they decided to meet at the State Hotel in downtown Kansas City, Missouri, because it was “equally inaccessible” for everyone involved in the movement at the time.

Equally inaccessible — unless you lived in Kansas City, of course.

Relatively new to the homophile movement, Drew Shafer showed up to the National Planning Conference of Homophile Organizations and gave a brief — but passionate — speech about the importance of improving communication and having everyone come together.

"This is where I feel like Drew is kind of manic. He wants to do everything, but he doesn't know where to start," says Scharlau.

Without missing a beat, Shafer and his friends started Kansas City’s first gay rights organization, the Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom.

Then, upon realizing he had access to his father’s printing press, Shafer also started the first LGBTQ magazine in the Midwest, “The Phoenix: Homophile Voices of Kansas City.”

At first glance, a lot of the magazines just look like art. Poetry. Short stories. Drawings.

But then you flip the page, and suddenly there’s a politely-worded argument about why gay people shouldn’t be kicked out of the military. Or a letter from Shafer warning readers about Kansas City cops practicing entrapment.

“It advertises bars, it advertises parties,” says Scharlau, "but then it also has some sort of hard-hitting, ‘What's going on in the country is wrong. Here's why you should fight back.’"

The approach worked. Originally created for a Kansas City audience, the magazine started cropping up in places like Iowa and Nebraska, connecting LGBTQ folks all over the Midwest to a community they had never had before.

“It was a lifeline to so many people,” says Hinds. “It told them they weren't alone.”

But Shafer didn’t stop there. In August 1966, the Phoenix agreed to be a publishing clearinghouse for the newly formed North American Conference of Homophile Organizations.

Shafer and his friends were now responsible for printing and mailing everyone’s magazines, newsletters and pamphlets — all from a basement in Shafer’s house.

“Kansas City was essentially the information distribution center for the homophile movement,” says Hinds.

It was an ambitious feat for a group that, less than six months earlier, had started with no more than 20 members. In a similarly determined move, Shafer and the society purchased a three-story house in 1968 to serve as the organization's headquarters, and wound up literally opening its doors to LGBTQ folks in need.

"He kind of viewed it almost as like a safe haven for people who needed a place to be... like a social safety network for people who had been outed," says Scharlau.

By 1968, the Phoenix Society had grown into a gay rights hub. That summer, Shafer met Mickey Ray, the man who would be his partner for 21 years.

It was an exciting time — but it eventually became too much. Tensions within the local and national homophile movement were starting to come to a head. And all of the work Shafer signed himself up for nationally and locally started to catch up with him.

"It was a busy time and things were going well until we began getting frequent media attention. Many within the gay community became afraid of the attention drawn to it and feared reprisals from their heterosexual counterparts," writes Mickey Ray of the Phoenix Society in the spring of 1969. "A sharp division was drawn between those who believed we had the right to be open and be ourselves, and those who wanted to keep the protected status quo."

The Stonewall uprising

On June 28, 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn in New York City's Greenwich Village. But what started out as a routine police raid turned into six nights of clashes, and led to an explosion in gay rights groups across the country. While the U.S. had already seen several well-documented confrontations between LGBTQ folks and the police, it was this raid that sparked a nationwide grassroots movement.

For that, we can partly thank Drew Shafer and members of the Phoenix Society for the work they had been doing for years out of Kansas City.

“I would argue that that is one of the reasons that the folks who started the groups after Stonewall were so successful," says Hinds. "Because that network had already been established as a result of these homophile organizations and their publications.”

But Stonewall also signified the end of the homophile movement. The renewed energy behind gay rights in 1969 attracted a younger crowd and resulted in a new, more radical approach, now known as the gay liberation movement.

“Stonewall is basically the beginning of the end for the Phoenix, too,” says Scharlau. “They had bit off so much with the clearinghouse. This event happens. It's like a true like flashpoint, right? They’re flooded.”

Shafer tried to keep the Phoenix Society open as long as he could, but by 1972, he had taken on $50,000 of debt, and advertising dollars for the magazine had withered.

Shafer remained present in the movement, but the Phoenix Society officially closed its doors.

Shafer and Ray lived happily in Kansas City for the next 14 years, until their story took a sad turn in the summer of 1986. When they went to volunteer at an AIDS hospice center, they discovered that Shafer was HIV positive.

Shafer died three years later at the age of 53.

“His loss was devastating to me at that time, but his memory and lessons now make him live on in my heart and mind,” writes Ray, who now lives in New York State. “No one smiled so often, tried so hard to please and kept his chin up in the worst of times like he did.”A hidden legacy

Even though homophile activists like Drew Shafer and other Phoenix Society members laid the groundwork for the modern gay rights movement, their legacy is mostly invisible in this country.

Most people don't know who early gay rights pioneers were — or that decades of work went into making the Stonewall uprising a catalyst for change.

"Without Drew, Stonewall isn't Stonewall," says Scharlau. "There's no way to have Stonewall become this national fulcrum and spark point without the work that Drew did. Without the ability to connect all these disparate local groups and kind of make a rallying cry of one city the rallying cry of the gay rights movement nationally."

One of the only places you can learn about the local Kansas City history is through a traveling exhibit, “Making History: Kansas City and the Rise of Gay Rights,” produced by students in the University of Missouri-Kansas City’s public history program. But even then, this kind of history rarely makes national headlines.

A rare exception was in September 2021, when the exhibit was dramatically removed from the Missouri State Capitol.

Even though the removal likely helped get the exhibit more attention than it would have otherwise, that's only a small consolation to LGBTQ advocates — after all, the story being censored was one about amplifying marginalized voices in the first place.

"The irony is painful," says Hinds, who helped curate the exhibit.

If you compare the articles in 1960s-era LGBTQ magazines with the more radical queer publications today, it's easy to feel like the gay rights movement has come a long way in the United States. But Scharlau warns against the notion that we're always moving forward.

“We tend to view American history as this constant march toward progress, which is total crap,” he says. “You gotta fight for that stuff. And if you don't fight for that, you can fall backward. Like it's not just this linear history."

"I think it's important that Drew did the work that he did. And that we keep pushing forward to make sure that everybody is treated fairly.”

The opening of the exhibit, “Making History: Kansas City and the Rise of Gay Rights,” at the Kansas City Public Library has been postponed since this episode aired, but the digital edition of the exhibit can be viewed online here.

This episode of A People's History of Kansas City was reported, produced and mixed by Mackenzie Martin with editing by Barb Shelly and Suzanne Hogan. The Frank Kameny clip is courtesy of Making Gay History. The recording of Drew Shafer is courtesy of the John J. Wilcox Jr. Archives at William Way LGBT Community Center.