Para leer este artículo en Español, haga clic aquí.

Dr. Mario Castro’s work as a pulmonologist at the University of Kansas Medical Center means he understands more than most what happens when there is a lack of information about the impact of the coronavirus.

“When I round on the wards with our COVID units, I would say half of my patients are either Hispanic or African American,” he said. “Unfortunately, those disparities that exist in the community translate all the way to the sickest patients affected by COVID in the hospital.”

Concerned about the health of Latinos, Castro, who is also vice chair of clinical and translational research at KU, made time to get the word out about the virus.

“I'm an immigrant myself, from Cuba, and have benefited from growing up here in Kansas City,” he said. “I definitely feel that it's part of my responsibility, my duty to give back to our community.”

Despite being less than 8% of the U.S. population in 2019, more than 20% of the country’s COVID-19 cases were contracted by people who identify as Latino or Hispanic, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They also made up 12% of the country’s coronavirus deaths.

But the complications of reaching the Latino population are as diverse as the people who belong to it.

“Nothing was really in Spanish in the beginning,” said Erica Andrade, chief program officer with El Centro, a nonprofit working to improve educational, social and economic opportunities for Latinos. “A lot of our clients were just needing a lot of information,” Andrade said.

Since then, El Centro has hosted digital forums and sponsored food giveaways that also served to educate about staying safe. The group is also developing a public service campaign for the vaccine rollout.

Spanish-language resources have expanded in the meantime but are not always as effective as they could be, said Dr. Manuel Solano, program director for the Community Health Council of Wyandotte County. His organization is enrolling county residents in health insurance and providing food deliveries for those quarantining.

“Everything that is related with the vaccine is written almost at a scientific level,” Solano said.

Meanwhile, conspiracy theories and misinformation are often presented in easy-to-understand terms.

“Latinos have a lot of information that they do not understand, so they have a lot of myths and a lot of misunderstanding,” he said. “We are not reaching most of the population because we are not writing the communications at the level that most people can read and write or listen.”

That communication gap leads many Latinos to depend on word of mouth for information.

Hector Alfonso Mompala is a press operator who lives in Overland Park and speaks fluent English. What he knows about the virus, he learned from family members and coworkers who have had COVID-19. Those conversations didn’t worry him too much, he said through a face mask while leaving El Rio Bravo supermarket in Kansas City, Kansas.

“If I’m going to get (COVID-19), I’ll get it,” said the 24-year-old. “But I don’t want to pass it on to anyone so I wear the mask.”

Mompala said he’d also likely pass on a chance to get a vaccine, when one becomes available to him.

Public service campaigns

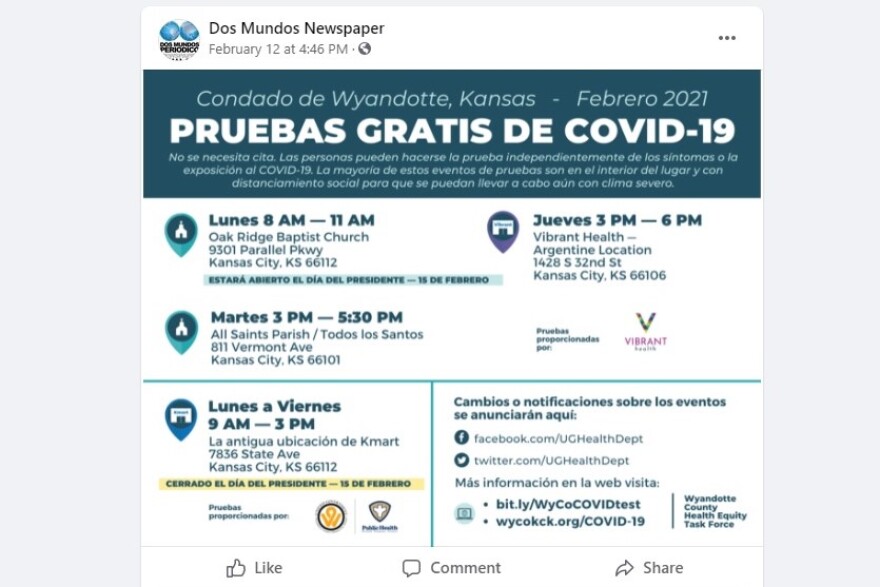

To fight vaccine skepticism, Wyandotte County’s Public Health Department is funding an effort to create educational videos, online graphics and more in both English and Spanish, all of it informed by advice from the county’s Health Equity Task Force.

Once the group crafts a culturally appropriate message, members circulate it on social media, TV, and radio, and in grocery stores, community centers, churches and elsewhere.

“They are well-known leaders of those communities, so they know what is needed,” said Mariana Ramirez, who co-chairs the task force’s testing subcommittee and directs the JUNTOS Center for Advancing Latino Health.

Since the pandemic began Ramirez’s organization has recruited Latinos to take part in vaccine trials and hosted a series of Spanish-language videos and podcasts.

The task force’s work has gained national attention, and a project led by the University of Kansas Medical Center will look to expand the model into nine other Kansas counties. It’s been awarded $3.5-million in grant funding from the National Institutes of Health.

“Many Latinos live in multigenerational houses,” said Solano, of the Community Health Council, so any health and safety guidance needs to take into account the possibility that school-aged kids might be living with their aging abuelita.

“Minorities and Latinos, we paid the price and a lot of deaths, because we didn't follow the recommendations,” said Solano. “But the recommendations were not written in a way that address our cultural needs.”

Faith also plays a big part in many Latino lives, which is why the task force engaged religious leaders — “and I’m not just talking about Catholic,” said El Centro’s Andrade. “There are a lot of very religiously conservative people that feel like putting anything foreign in your body is, like, to be suspected of.”

As he took out the trash at work, grocery store employee Andres Torres Sanchez pointed out another important conduit for information: local Spanish-language TV and radio. His station of choice is KYYS, better known as La X 1250 AM, which features Wyandotte County coronavirus graphics on their website.

Steve Downing is general manager of Telemundo KC, which he said reaches more TVs in the area than any other Spanish-language station.

“We do deliver the news, deliver information, in a way that's going to be relevant to the Hispanic community,” Downing said. “There's a lot of those things that may seem simple to us, but for someone that's maybe a recent immigrant, living in this country for not that long … most things are done differently.”

Those recent immigrants are often the hardest to reach, said Mariana Ramirez.

“And then there's also our undocumented population that forever have been trying to stay, you know, like hiding,” she said. “Now we're asking them with contact tracing, for example, to come up front and share their contacts with us, and also to get it all on a database of the public health department to receive the vaccine.”

To combat that fear, Ramirez said public health officials need to be completely transparent about how those personal details will be used, and whether they could end up in the hands of an agency like Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Additionally, “when we think about why the Latino population were so severely affected, a lot of times it was because of their place of employment,” said KU Med Center’s Mario Castro. “They were in the front lines, those lower paying jobs, and in close proximity to others.”

He’d like to see more employers give their workers time off to quarantine, recover, or get the COVID-19 vaccine.

It’s one possible solution to the country’s looming dilemma — how to get 80-90% of the population inoculated to achieve herd immunity.

“We need to stop thinking in the box when you’re thinking about how to get people vaccinated,” Andrade said. “You have first generation (Latinos), you have new immigrants, you have all different kinds. And you can not assume that what works with one population is going to work with another.”