SCOTT CITY, Kansas — Bouncing over the sand sage-covered hills in his pickup truck, rancher Stacy Hoeme combs the shortgrass prairie of his ranch searching for leks — the mating grounds of the lesser prairie chicken.

Despite being one of the bird’s biggest champions and most successful conservators, Hoeme opposes putting the bird on the federal threatened species list.

“I just want them to maintain the birds,” he said. “It’s a big hassle when they get listed for the ranchers.”

The small, Nerf football-sized bird has become an unlikely proxy in a 26-year tug-of-war between industry and conservationists and their competing visions for how to use the riches of America’s Great Plains.

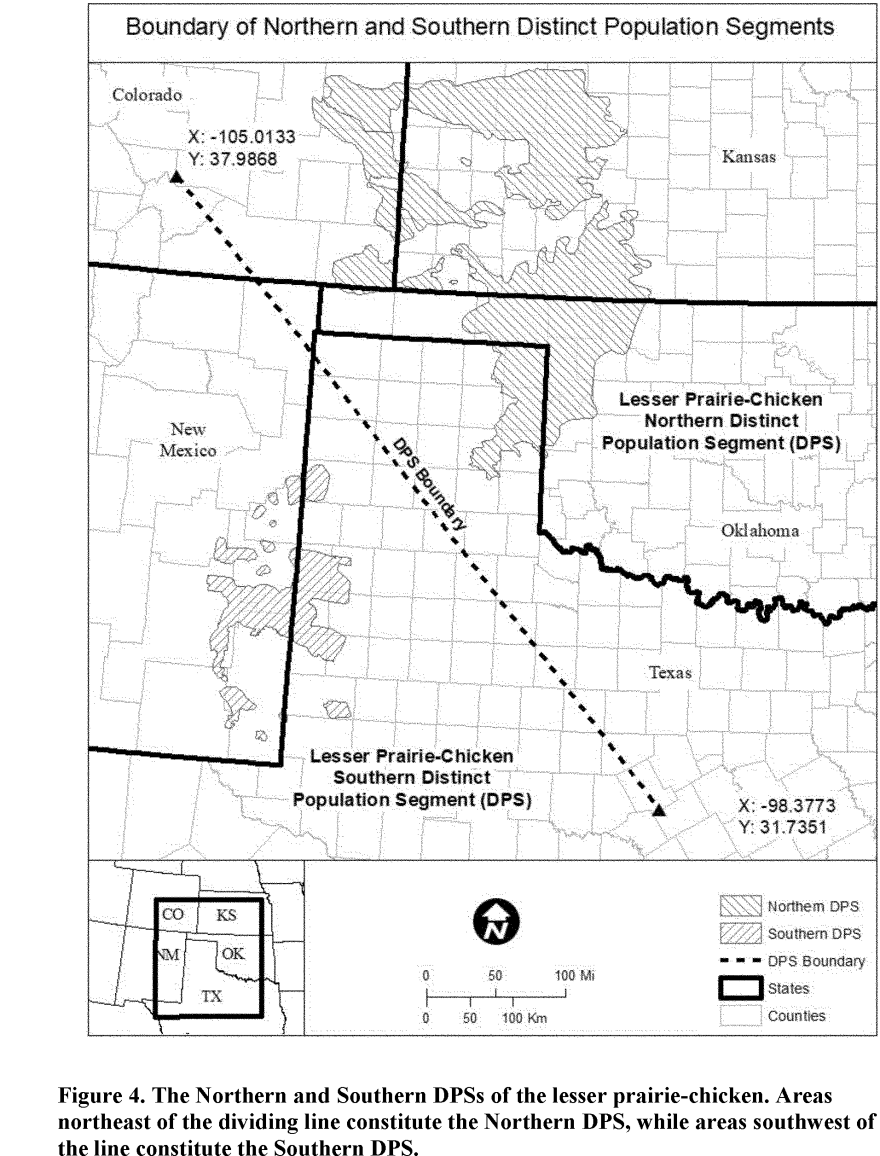

This year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service proposed listing the bird as threatened in Kansas and Oklahoma and endangered in Texas and New Mexico. That status puts limits on agriculture and oil and gas exploration on land that overlaps the bird’s territory — and underscores the reflexive differences between Democrats and Republicans where nature and commerce collide.

Hoeme’s 10,000-acre ranch along the Smoky Hill River attracts visitors from as far as Russia and Australia to see the birds during their spring mating season.

For birders, environmentalists, researchers and Hoeme, the birds are captivating. Males are striped with bursts of ochre-colored eyeshadow and rust-colored air sacks under their necks. The charismatic but exceedingly rare grouse is native to Kansas’ once abundant short-grass prairie. It’s a few inches smaller than its relative, the greater prairie chicken, and prefers shrubs and short grasses to tallgrass prairie.

More than 27,000 birds still inhabit a five-state region across Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas. About 62% dwell in western Kansas south of Interstate 70 and north of the Arkansas River.

Theoretically, the listing is straightforward. An unstable population coupled with a drastic loss of habitat should qualify the bird for threatened or endangered status.

But unlike the listing of the bald eagle — one of the Endangered Species Act’s biggest success stories — there is no single chemical to ban that would save the imperiled bird. Instead, it needs habitat.

Death by 1,000 cuts

Wayne Walker owns a private land bank aimed at conserving the bird.

“It’s death by 1,000 cuts,” he said.

Back in 1932, for instance, a single flock of chickens in Seward County, Kansas, had possibly 15,000 birds. Today, the population is barely double that size. The broader region’s population has fallen from roughly 175,000 in the late 1960s to just over 27,000 today.

“It’s a ranch over here. It’s a transmission line over there. It’s a highway over there,” Walker said. “You know, oil and gas, wind farms, solar.”

In the case of the lesser prairie chicken, the loss of habitat has been debilitating.

Before white settlement, the Great Plains ran thick with the grouse, with bison, with prairie dogs. Now it’s America’s breadbasket, a nexus of the meatpacking industry and one of the most productive oil and gas drilling regions in the country, the Permian Basin. The birds have lost an estimated 83% to 90% of their habitat and the population has plummeted.

Because of the real estate the bird occupies, it’s become a cause for conservationists and a thorn in the side of energy extractors, farmers and some ranchers.

Political chicken

Complicating things further, the bird has also become a purity test for politicians — support conservation and inhibit fossil fuel extraction, or support industry and the rights of private landowners. That makes the battle for the bird to be listed long and litigious.

At best, the renewed effort to list the bird as threatened under the Endangered Species Act can be viewed as a good faith effort to save a species hurtling toward extinction. At worst, critics view it as a Democrat in the White House leveraging environmental rules to shadow-ban oil and gas development — a way to infringe on private property rights.

Republicans in Kansas have long opposed listing the bird as threatened or endangered. Republican former Gov. Sam Brownback blasted the Obama-era listing and joined a lawsuit with the state of Oklahoma challenging it when the bird was first listed in 2014.

Brownback labeled it “another example of the Obama administration aggressively and unnecessarily intruding into our daily lives.”

That same year, speaking to an agriculture group, Republican then-Sen. Pat Roberts said: “The number one issue in Kansas is the Lesser Prairie Chicken.”

That year, the bird was formally listed and it remained on the list for a short stint before a U.S. District Court in Texas vacated the decision in 2015 and the bird was plucked from its protected perch. The decision ruled the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had not thoroughly considered the impact of voluntary conservation programs.

This year, the players are different but the stage remains the same.

Republicans in Kansas remain opposed. In letters to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, Sens. Jerry Moran and Roger Marshall and Reps. Jake LaTurner, Ron Estes and Tracey Mann said the threatened listing would be overly burdensome to landowners, and unnecessary. After all, the bird’s population doubled since 2013 without the listing.

But conservation groups say that the rebound in population followed a drought, and shouldn’t be credited to a voluntary effort through the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies.

That collaboration marked the most heralded effort to restore the prairie chickens without strict federal rules — instead billing developers and landowners for damaging habitat. Environmentalists and other conservation groups said it was a failure.

“It’s a fumble. It’s a bad fumble,” Walker said. “You didn’t-even-get-out-of-your-own-end-zone kind of fumble.”

Official comments made by the Center for Biological Diversity, one of the groups that sued to have the bird re-listed, accused the program of being “self-dealing” by using conservation funds to pay for staff salaries, and called it “a shambolic house of cards” for failing to implement a mitigation strategy that would actually save the birds.

The species has recovered from a blow after a drought in 2013, but “the populations have been so low for so long that it's really hard for them to recover because they have this boom-bust population cycle,” said Jackie Augustine, who heads the Kansas Audubon Society and researched both lesser and greater prairie chickens.

“They are in danger of going extinct, and so that's why this listing is warranted,” she said.

Others like Edward Cross, president of the Kansas Independent Oil and Gas Association, see the listing as an end-run by conservation groups to stop oil and gas drilling. He talked about a “sue-and-settle” pattern conservation groups use to leverage the federal law.

“The environmental activist groups were using the Endangered Species Act,” he said, “as a way of, you know, stopping some of the industry activities that they opposed.”

Some environmentalists concede as much. Michael Robinson, an advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity, said his group sees larger issues like climate change as an existential threat to the species.

“So we address that directly and we make no apology for pointing out the fact,” he said. “That oil and gas drilling is contributing to these deadly heat waves, for people and lesser prairie chickens alike.”

Jeremy Bruskotter, who studies environmental policy at the Ohio State University, said the Biden administration inherited a long-running fight, one that can define a split between Republicans and Democrats.

“You know, for these heavily politicized and litigated listings, they are crossing multiple administrations,” said Bruskotter. “And so, it's hard to point to the administration and say, ‘They're responsible for X.’”

A public comment period on whether to list the bird has been extended through the end of August. If the final rule is published, the prairie chicken would make it back onto the federal list. But that doesn’t guarantee an end to legal challenges by industry groups who feel threatened by the regulations.

The road ahead

People like Augustine, Hoeme and others believe it will take a myriad of programs with or without a potential ESA listing to save the bird.

One of the biggest benefits to the bird’s conservation thus far has been the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s conservation reserve program which pays farmers to convert cropland to grassland for a set amount of time.

Right now, “the fate of the species largely relies on a 10-15 year Farm Bill program,” said Matt Bain, a western Kansas conservation program manager at the Nature Conservancy’s Smoky Valley Ranch.

Walker is also a proponent of creating strongholds of habitat through conservation easements, where landowners could receive market value or better for selling conservation credits and converting their land to habitat.

Rob Manes, director of the Kansas Nature Conservancy, said that because the bird is located across private land, “there’s always this threat, this fear of regulation of how a person runs their privately owned ranch.”

He thinks a kitchen sink of programs needs to be used to save the bird, whether that’s conservation reserve program land, market-based solutions, or other voluntary conservation efforts. Ultimately, Manes said coaxing landowners with voluntary programs will be most important.

“If we don’t have voluntary cooperation from landowners and energy producers as well,” he said, “we got a rough road ahead of us”

Abigail Censky is the political reporter for the Kansas News Service. You can follow her on Twitter @AbigailCensky or email her at abigailcensky (at) kcur (dot) org.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.