Tommy E. Williams, 55, regrets he didn’t pause and reflect for even a minute on September 10, 1990.

He was hanging out with friends at a bus stop at 39th and Prospect Avenue in Kansas City, Missouri, when two men drove up and started an argument. He said his 13-year-old brother was with him when one of the men in the car chided them about wearing the wrong colors, a reference to the reds and blues associated with L.A.- based Bloods and Crips.

Offshoots of the rival gangs had formed outside of coastal cities over the years,

including in Kansas City.

Remembering that day more than 32 years ago during an interview at the Crossroads Correctional Center in Cameron, Missouri, Williams said he wasn’t affiliated with a gang, but his cousin was a Crip. He had friends who were Crips and Bloods. Violent feuding was part of life on the streets.

“We sold drugs and that was our life,” Williams said. “We felt like that's all we had at the time because we didn't have, you know what I'm saying, a lot of jobs then. And then when the drug trade came along, that's what we cling to.”

The crack cocaine epidemic took hold in Kansas City in the mid-1980s and continued through the 1990s. To cling to the drug trade also meant clinging to guns.

Williams said he wasn’t carrying a gun at the time of the incident that fall night. But he didn’t need to.

When one of the two men threw a beer bottle that hit Williams, his little brother turned to run and tripped. Thinking the boy had been shot, Williams said, he picked up a gun that was lying by a trash can next to the bus stop and opened fire.

“It was a gun for anybody who grabbed it if there was a situation,” Williams said.

If members of his group knew one of their people would be hanging out on the street, they knew someone, at some point, would likely need a gun. So they made sure one was accessible.

“In a situation where we grew up, you keep a weapon somewhere,” Williams explained. “People have problems. Like you’re dating their girlfriend and they’re mad, somebody’s jealous of your car or your shoes and wants to take them. So sometimes you just have to protect yourself.”

The gun was left by the trash can, Williams said, so no one would have it on them when the police arrived.

Williams shot and hit the driver, Arland Harrison, 29, and the passenger, Maurice Robinson, 26. The car took off, but a block south on Prospect, Harrison slumped over from the gunshot wound to his face, according to police records.

A crisis over gun violence

KCUR visited Williams at Crossroads because Kansas City has been at the center of a national debate over gun violence in recent years.

Kansas City has had a record-setting number of homicides in the last several years, the vast majority caused by guns.

Non-fatal shootings are routinely four and five times higher than homicides.

Meanwhile, Kansas and Missouri have some of the most lenient gun laws in the country.

The Giffords Law Center gives both states an “F” rating, with strength in gun laws ranking in the bottom five nationally.

As federal, state and local officials identify firearm deaths (including suicides) as a public health crisis, KCUR reached out to community members at listening sessions and through our text exchange to hear what people in the area were thinking about the topic of gun violence.

One of the revelations: Neither gun laws nor the threat of prison are a deterrent to many people who commit gun crimes.

After people told us this, we wanted to ask someone living with the consequences of gun violence to get their perspective.

Is there a message that speaks to those who don’t know their experience? Has their time in prison altered their thinking? Would they have acted differently if they’d known the consequences?

The answer for Tommy Williams is yes.

Sitting across a rectangular table in a small, gray room with glass looking into the adjacent prison visiting room, Williams wore a gray, V-neck prison tunic and baggy gray pants, his name and inmate number on a strip of white cloth on his chest.

He said he thinks every day — so far almost 12,000 days of his life sentence — about the moment he pulled the trigger.

“I don’t know if it was three minutes or nine minutes that changed everything,” Williams said. “That one incident changed the course of my whole life.”

In October 1991, a jury found Williams guilty of first-degree murder, first-degree assault and two counts of armed criminal action. A month later, a judge sentenced him to life without parole on the murder charge, with two additional consecutive life sentences on the other two charges.

He was taken into custody and has remained behind bars for more than three decades.

“I’m a grown man now. I would do things different,” he said.

“Like neutralize the situation. Because I wouldn’t want to be here for 30 years and put my family through all this.”

Family trauma

Williams’ sister, Kim Williams-Dennis, 51, has been trying to get his case reopened in recent years. The family believes Williams did not get a fair trial. But there is no new evidence in the case and the prosecutor is no longer with Jackson County.

Williams’ little brother, Keith, who was with Tommy when the shooting occurred, was later shot and killed in their mother’s home.

Sitting outside a grocery store where she had just finished shopping, Williams-Dennis grew teary talking about how gun violence has taken a toll on the whole family.

“I see my mother cry. I cry,” she said. “Others, when they talk to him on the phone, they’re happy and then when they hang up, they’re sad because everyone wants him home.”

She said her big brother was a role model who took care of his little brother, sister and cousins, but who made some bad choices.

“It took a toll on me because I knew he wasn’t that type of person,” she said. “He just wished he’d handled things differently. He wanted to make amends with the (victim's) family and they told him he couldn’t write a letter, he had to stay away. We talk about it all the time.”

What he’s learned

It took Williams many years to express his remorse.

“I was angry,” he said. He claims he’d acted in self defense to protect himself and his little brother.

The early years of incarceration were not easy. Williams spent time in administrative segregation, known as “the hole,” where inmates are confined to solitary cells for extended periods of time.

But participating in training and conflict resolution programs helped change his perspective.

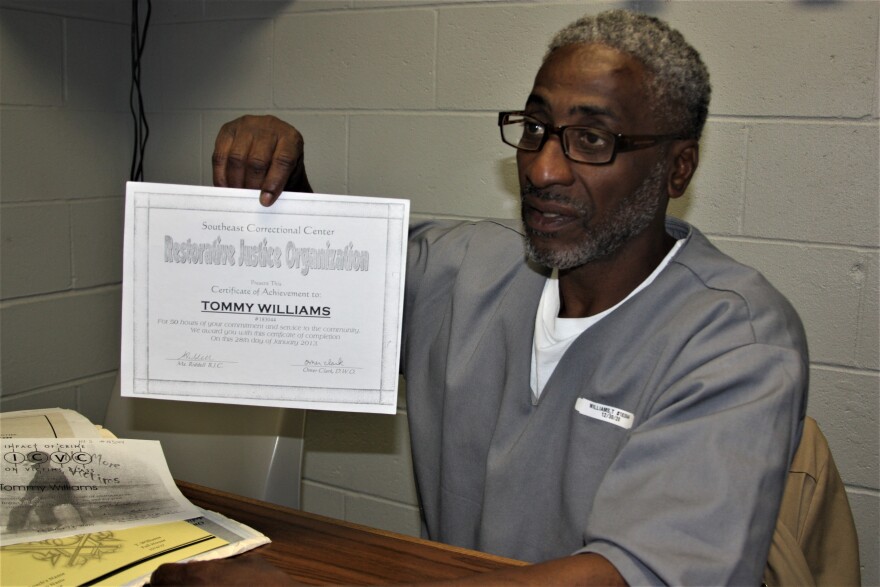

Williams opened an envelope full of worn documents and pulled out a certificate for completion of a carpentry class and training toward a commercial driver’s license.

He held up a faded black and white page from a class called ICVC, Impact of Crime on Victims, issued in 2005. Another document celebrated “50 hours of commitment and service to the community” from the Restorative Justice Organization.

Williams' eyes are tired and his voice is soft. He said he regrets that he didn’t have any of these skills at the time he pulled the trigger decades ago.

“(To) give yourself a chance to think, why am I gonna harm somebody?” he said. “This is a human being, why would I want to hurt somebody? Just think if it was your child, or one of your family members.”

Williams said he tries to talk to younger inmates about the impact of incarceration and how his thinking has changed over the years. He said they’re not interested in what he has to say.

Like a 'vacation'

Crossroads Correctional Center is a maximum and medium facility prison located in Cameron, in northwest Missouri, less than an hour outside of Kansas City. East Pence Road comes off North Walnut Street outside of Cameron, where the prison first appears as a set of buildings that look like Monopoly hotels in the middle of expansive grass fields. A high fence topped with rolls of barbed wire surrounds the buildings, which are painted institutional tan.

Inmates at Crossroads have a varying degree of access to programs and training toward a high school certificate or GED, adult literacy, or vocational education in trades such as auto mechanics, plumbing, welding and electrical skills.

The threat of prison doesn’t give some young inmates a reason to avoid gun violence, Williams has concluded after years of watching them come and go and come back as repeat offenders.

“It pisses me off,” he snarled.

He said they see people they know from the streets in prison, brag about their prison stints and wear their time on the inside as a badge of honor.

“They think this is a Hotel Rwanda or something. They come here and get high and party and have fun. They come here like it was a vacation. Then they go right back out to the streets, get a gun, and rob someone.”

Williams said the young people he sees are not thinking about how to create a different life when they get out, to change their environment or the people they hang with. They bring their street life to the prison and take prison life back out to the street.

Williams tries to tell them there are alternative ways to cope with the stress of life on the outside.

“You don’t necessarily have to go to church if you’re not a religious person,” he said. “Take some deep breaths. Go fishing. Get married. Your wife, she’ll hold you down,” he chuckled.

Some ways forward

But Williams also sees the flaws in the system. It’s clear, he said, that punishing young inmates for using drugs does not help them. They need treatment. A federal report released last year found former inmates who received drug treatment while incarcerated and once they were out had a significantly lower likelihood of returning to prison.

As for gun laws, Williams said he believes in the constitutional right of adult citizens who meet the criteria to own a weapon, with the exception of military-style assault weapons. But background checks need to be tightened.

“Your credibility should be almost like you trying to get a house or bank account,” he said. “Make sure your mental state is good. Everybody’s got to be ‘A-1.’ You shouldn’t be able to get a weapon if you’re not qualified. That’s serious.”

At the same time, he said no one on the streets pays the least bit of attention to gun laws, nor do they affect how easy it is to get a gun.

“You can get a gun at the car wash,” he said. “Somebody will pull up and say ‘Hey, man, I got a couple of guns, you interested in buying one?’”

But the guns aren't the problem, according to Williams. It's people.

As our interview was wrapping up, an assistant warden opened the door with a reminder not to take pictures of anyone in the adjacent visiting room. Williams engaged the official enthusiastically.

“Mr. Drake, how you doing?” he said.

“Good, how are you?” Drake replied.

“I was just letting her know I know a lot of the staff here and I was talking to her about the gun violence,” Williams told him. “This is one of the interviews.”

The warden nodded and closed the door without saying anything.

Williams has given a few other interviews about gun violence over the years, mainly with anti-violence activists who hope others might learn from his story. He believes he has a potent message.

“If you could experience the life I’ve lived for the last 30 years … not one day of freedom … waking up at five in the morning … not eating what you want to eat … not talking to your family when you want to,” he said. “Why would you want to be in prison? That’s like the dumbest thing a person could say.”