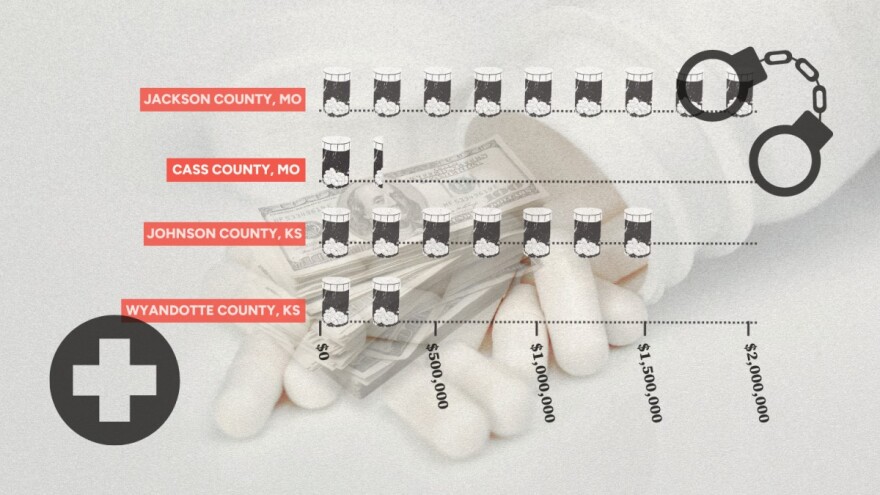

Johnson County, Kansas, spent the biggest piece of its opioid settlement windfall so far cracking down on drugs.

Jackson County, Missouri, chose to put its dollars into treatment.

In both cases, the money came from massive legal settlements with opioid makers, distributors and retailers.

The counties’ choices illustrate opposite approaches to tackling opioid addiction, which kills an estimated 130 people nationally every day.

One way cracks down on drug traffic supply — feeding money to agencies that continue a war on drugs. The other tries to push down demand by helping people fight addiction, rerouting money to social services. Public health experts overwhelmingly side with treatment, saying the country’s generations-long war on drugs has not worked.

Now city and county governments find themselves sending settlement money into idiosyncratic directions — fielding requests from agencies that most often fall into the categories of law enforcement or health care.

Payouts so far have ranged from $2.4 million to Kansas City to $4,500 to Westwood. The Kansas City Council voted to spend its share on treatment programs and the respite beds that provide a sanctuary to people trying to get clean. A spokeswoman said contracts would be awarded in the next four to six weeks.

Health care experts, who see the settlement windfall as a one-time shot at stopping the epidemic, watch and hope that politicians don’t squander the chance the money provides.

“We have a multiyear opportunity to build a substance use prevention, treatment and recovery infrastructure that does not currently exist,” said Emily Hage, president and CEO of First Call, a Kansas City nonprofit focused on helping people struggling with drug and alcohol addiction. “The reality is, it’s very rare we have 18 years of funding for anything.”

Companies that made, shipped and sold opioid painkillers like OxyContin and Vicodin will pay out a combined $50 billion across the country to settle claims that their drugs led thousands of Americans down the path to drug addiction.

Opioid settlement payouts, which will be made to thousands of communities across the country over 18 years, include a nationwide settlement valued at $26 billion that pulls in the pharmaceutical distributors McKesson, AmerisourceBergen and Cardinal Health, and the manufacturer Johnson & Johnson. Settlements of lawsuits involving other companies, including the pharmacy chains CVS, Walgreens and Walmart, are in the works.

Meanwhile, a settlement involving Purdue Pharma, the Sackler-family-owned pharmaceutical company widely seen as lighting the fire that started the opioid crisis, is on hold pending the company’s bankruptcy case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

All told, Missouri hopes to get $900 million from the settlements. Kansas expects about $340 million. In both states, a portion of those funds goes to cities and counties, but how much and other details vary by state.

In Missouri, the legislature makes the spending choices about the state’s share of the settlement. Of the $71.5 million Missouri received so far, $14.3 million went to the departments of mental health, health and senior services, social services, corrections and the office of administration.

Local governments, including 93 counties, 50 cities and three political subdivisions, have control of their share of the money — so far, about $29 million. The state’s first report on the settlement funds found about 11% of the local government dollars have been spent.

In Kansas, 75% of the money goes to the Kansas Fights Addiction Fund. That’s controlled by a grant review board that doles out the money to cities, counties, nonprofits and, beginning next year, for-profit entities. The remaining 25% gets divided between cities and counties.

Chris Teters, an assistant attorney general in Kansas, said many guardrails in place both in the opioid settlement agreements and in state law are designed to keep money directed toward addressing the state’s addiction crisis.

“This is a lot of money,” he said. “But it’s not a lot of money.”

If it’s going to make a difference, he said, it needs to be spent wisely.

The Kansas grant review board is spending $1.5 million on a study to explore which investments will best fight the opioid epidemic.

“We’re not looking for utopia,” said Janine Hron, the University of Kansas researcher who is leading the study. “But we are looking for better.”

So far, the KFA board has awarded about $6 million in grants related to treatment programs and about $4 million for prevention.

Most of the opioid settlements stipulate that the majority of the money must be spent on addiction treatment and prevention — and not to patch random budget holes.

Public officials want to avoid what happened to the $246 billion tobacco settlement of the 1990s, which fell short on helping people quit or avoid smoking.

Spending guidelines for the opioid money include harm reduction efforts, like purchasing and distributing syringes and naloxone, a drug used to reverse opioid overdoses. Or treatment efforts, like providing medication-assisted care to help people recover, and training first responders to steer patients to treatment.

Money can also go into public information campaigns. And local governments can use a certain amount of money to reimburse themselves for past costs related to the opioid crisis.

But public health experts worry that, already, some money is being spent in ways that won’t actually change the landscape or help people who are addicted to opioids. Hage of First Call said Johnson County Commissioners’ vote to put three quarters of recent settlement spending into the sheriff’s department, including $235,000 on mail scanners for the jail, is a good example of that.

“Yes, technically, the drug scanning equipment technically fits (spending guidelines),” she said. “The intention … is to proactively reverse the impact of the opioid crisis. Is a mail scanner doing that?”

At a February meeting of the Johnson County Board of Commissioners, members discussed whether the mail scanners were an appropriate use of the county’s settlement dollars, anticipated to eventually reach $10 million. The scanners would only be used for legal mail, like letters that come to inmates from their lawyers. Officials said personal mail is already sent offsite to be scanned and is returned in digital form.

Chairman Mike Kelly, one of two commissioners to vote against funding the scanners, said he didn’t believe the expenditure fit the intent of the settlement agreements. Fifth District Commissioner Michael Ashcraft also voted no, saying he wanted to see an overall spending plan before any more money is spent. The county has already allocated $100,000 to both United Community Services and the Johnson County Prevention and Recovery Coalition

But the majority of commissioners voted to buy the scanners, along with other items like Narcan, a cardiac monitor, respirators and face shields and two down-draft tables, to suck potentially dangerous particulates out of the air.

The complete list, which also included drug testing costs and salaries, came to just under $658,000. While allocations also went to the county’s Adult Drug Court program, its first responders, and to the Department of Health and Environment, 72% of the money went to the sheriff’s department.

“The elephant that’s in the room is supply,” said Third District Commissioner Charlotte O’Hara. “We can have all the programs in the world, but if the supply is absolutely overwhelming everybody … this is a tsunami heading towards us.”

Sheriff Calvin Hayden told commissioners his department had recovered enough fentanyl to fill a conference table in the meeting room. Treatment and education are important, he said, but enforcement matters.

“Every time my guys take a five- or 10-pound bag of fentanyl off the market,” Hayden said, “those are lives saved.”

The sentiment is common, said Dr. Jeff Singer, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute. But he said local officials need to realize that if drugs can’t even be kept out of jails, spending more money on law enforcement to quash supply everywhere else is unlikely to work.

When police have tried to crackdown on drugs, he added, they’ve only driven people to more dangerous drugs.

Enforcement against illegal prescription painkillers led to a rise in heroin. Clampdowns on heroin were followed by a rise in fentanyl — something that could be made in a lab to be small, highly concentrated and deadly potent. And as fentanyl is targeted by law enforcement, more highly potent and dangerous opioid drugs, like Xylazine, or “tranq,” spills into the market.

“The harder the law enforcement,” Singer said, “the harder the drug.”

Tearing down barriers that prevent organizations from offering harm reduction services, like Narcan or clean needles, is a far wiser use of the opioid settlement money, Singer said.

The crisis isn’t abating.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says drug overdoses killed more than 110,000 people in the United States during the 12-month period that ended in October. Many of those deaths, experts said, were caused by fentanyl and communities are struggling to help. Other drugs laced with fentanyl, which is 50-times stronger than heroin, are often a deadly combination.

In Missouri, fentanyl was to blame for 72% of the 2,180 overdose deaths in the state in 2022, compared with about half of the 1,366 overdose deaths in the state five years earlier. And the drug caused 56% of the 738 overdose deaths in Kansas in 2022, compared with 10% of the state’s 326 overdose deaths in 2017.

That’s why Cass County Health Director Sarah Czech is glad the majority of the $13,700 of settlement dollars her county has spent so far have gone toward harm reduction strategies like Narcan and fentanyl test strips. The county is also putting money toward education.

“We are in the business of prevention,” Czech said.

Keeping people alive so they can get help is critical, experts said. But so is having the capacity at treatment centers to provide care.

University Health’s Center for Recovery and Wellness, the project that will get $3 million from Jackson County, will open in a new facility at 2020 Charlotte St. this summer, making room to treat 1,500 patients for substance and opioid addiction. The center’s current space only has room for 750.

While there will probably always be more need than capacity, said Charlie Shields, University Health’s president and CEO, the new facility will help.

“You’ve got to work towards breaking the cycle of addiction,” he said. “The more money you can put up front, the better outcomes you’re going to have on the back end.”

This story was originally published by The Beacon Kansas City, a fellow member of the KC Media Collective.