On August 6, voters will decide the fate of Amendment 1 which would give the state legislature the ability to exempt certain child care facilities from property taxes.

Approving this amendment does not mean all child care facilities in Missouri are immediately exempt from paying property taxes. Rather, it would allow the legislature to enact policies providing the tax exemption.

The Missouri Constitution requires voters to approve all new property tax exemptions before it can be codified into law.

However, the ballot language surrounding this amendment lacks details about which child care facilities, or associated properties, would qualify for the exemption. Irma Arteaga, an associate professor at the Truman School of Public Affairs at the University of Missouri, said lawmakers likely intended for the language to be general.

“(Lawmakers) want to provide some discretion to the people who are going to implement them, and so that can be good or bad,” Arteaga said. “It really depends. So sometimes lawmakers do that, because they say, ‘Well, we're not experts, so let's leave this to the experts.’”

Arteaga says that because the details are unclear, voters should consider the property tax exemptions in the amendment to affect child care providers generally.

This means that right now, it hasn’t been decided whether licensed childcare facilities will be the only ones eligible for potential property tax exemptions, or whether home-based childcare centers and other providers will be able to benefit too.

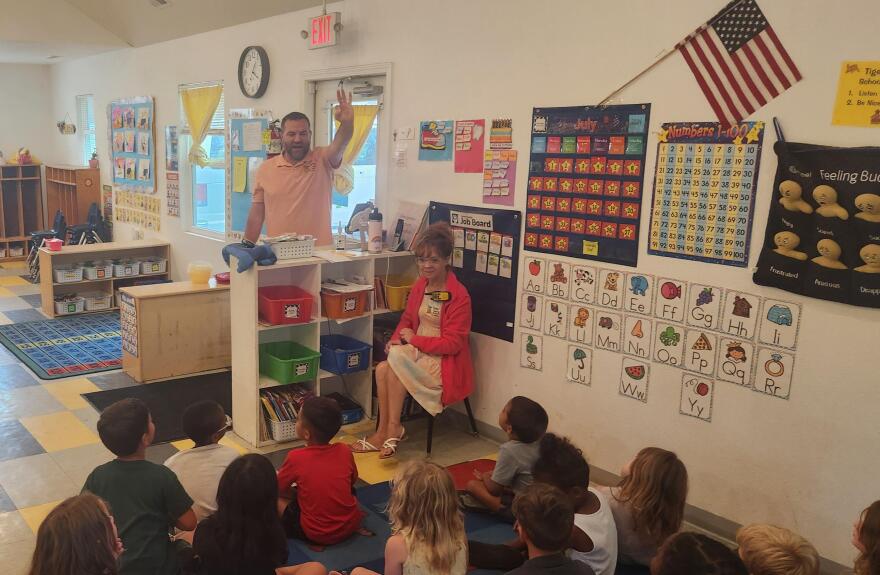

Paul Prevo is the founder of Tiger Tots, a child care business with two locations in Columbia and a third in progress. Prevo says that a property tax exemption would cut costs for Tiger Tots, but he believes that if it’s passed, centers should be required to pass on those savings to families rather than pocketing the money.

Prevo also believes that property tax exemptions should focus on education-based centers, but recognizes that’s tough in rural areas.

Amanda Coleman, vice president of family and early childhood development at Community Partnership of the Ozarks, said that in the Ozarks region, including home-based centers would be a big move to address childcare deserts.

“There is a huge space for increasing our home base provider numbers across the state it when you're thinking about the logistics of what it costs, and what it takes to open a childcare facility, home based providers - that's that's where you can start and make a huge impact,” Coleman said.

Child care desert

Nationwide, many families, including those in Missouri, are struggling to find adequate child care options, as child care deserts exist in every state across the country.

The Center for Progress defines a child care desert as an area “with more than 50 children under age 5 that contains either no child care providers or so few options that there are more than three times as many children as licensed child care slots.”

Using this definition, 54% of Missourians live in a child care desert, just over the national average of 51% in 2020. By this definition, most counties in Missouri are child care deserts.

The Center for American Progress did a study in 2020 using a distance-based approach, which measured families' access to a child care facility within a 20-minute drive regardless of political division. The resulting map indicates that most Missouri families have inadequate access to child care.

Additionally, many of the areas that are considered to be child care deserts are in rural regions of the state. Many of these areas are also home to residents experiencing some degree of poverty.

In the Ozarks region, Coleman said the Community Partnership organization serves 17 counties — 16 of which are considered deserts. Coleman said that some counties have little to no childcare options, meaning that parents must travel long distances, leave children with family, or quit their own jobs to care for their children.

"In Greene County where we're not a desert, technically ... most of our providers are operating with a waitlist. And when you talk about infant and toddler care, that becomes even more significant. In Springfield alone, we have about a 2000 shortage of infant care slots needed based on the amount of kids that we have in our community," Coleman said. "If you take that number, and you apply it to a rural area where your county doesn't even have a childcare provider — I mean — where are you going to go?"

One barrier to accessing child care is the price. According to 2021 data from Child Care Aware, the average cost of putting a toddler into center-based child care in Missouri is over $8,000 a year, with prices for infant care averaging more than $10,000 a year.

Inadequate access to child care services can be detrimental to the state’s economy. Some parents decide not to enter the labor force if they can’t find someone to take care of their kids.

“A parent cannot go to work if they don't feel that there's an affordable, high quality, safe place for their kids or children to go to during the day when they are at work,” said Kara Corches, the interim president and CEO and senior vice president of governmental affairs for the Missouri Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

Based on a 2021 report, the Missouri Chamber of Commerce estimates that the state’s child care shortage caused an economic loss of $1.35 billion in 2021, with 9% of Missouri parents leaving their jobs due to child care-related issues.

“We know that child care is not just an issue for working parents to care about. This really is a statewide economic issue that everybody should care about,” said Corches.

Corches says child care is a complicated industry, as providers must keep prices affordable enough for parents yet also balance expenses incurred by operating the business.

“When they can't just increase costs, it puts them in a really challenging situation,” Corches said. “That's why we saw the child care crisis before the pandemic, and then it just got exacerbated during the pandemic.”

Jerome Katz, a business professor at the Chaifetz School of Business at St. Louis University, said that child care providers often struggle to pay employees competitive wages.

According to a report from the Missouri Economic Research and Information Center, the average hourly wage of a child care worker in the state was $14.55. In comparison, an average Missouri retail worker is paid $17.17 an hour.

The work required by child care providers can often be more taxing than other jobs paying comparable wages.

“If it's done well, child care is a pretty demanding physically and psychically demanding kind of job,” Katz said.

Talking taxes

If approved, the amendment would allow the legislature to provide property tax exemptions to eligible child care facilities. However, data shows that, for some facilities, the savings from this tax cut will be a small percentage of annual revenue.

Katz provided access to child care data compiled by Bizminer, an industry benchmarking website. It surveyed the finances of 515 small child care centers, which on average have a revenue of more than $1 million.

The data showed that these facilities spent less than 4.28% of its annual revenue, or roughly $50,000, on taxes in 2022. That figure represents all taxes paid, not just property taxes.

Katz said that the savings facilities could receive from property tax exemptions would be less than the revenue earned by providing care to an additional child.

While the amendment could alleviate some financial stress for child care providers, he doesn’t see it as a solution for the shortage of child care options in the state.

“I think the amendment is playing to the audience, more than actually making a difference,” Katz said.

In Columbia, Paul Prevo said that a tax exemption could help the Tiger Tots facility by keeping expenses down and preventing price hikes for families seeking child care services.

“When your property taxes are increasing year over year, those costs begin to add up,” Prevo said.

In addition to keeping prices low for parents seeking child care services, Prevo said the money saved by the tax exemption could be put back into the facility.

For example, Tiger Tots built a new deck with COVID-19 funds, and Prevo feels that the availability of additional funds could be reinvested into further property improvements.

Arteaga said that this amendment may have less of an impact in rural areas because property taxes tend to be lower. Most Missouri counties that are child care deserts have a lower-than-average property tax burden.

Corches says that childcare deserts are a multifaceted issue, and it may take several methods to address the shortage

“It's gonna take all the tools in the toolbox,” Corches said.

'Robbing Peter to pay Paul'

Providing a property tax exemption for child care facilities means that any other state program that relies on these taxes will receive fewer funds.

One such program specifically mentioned in the ballot language is the Blind Pension Fund, which provides funds for those who are blind and meet certain requirements, such as not holding property below $30,000. Many beneficiaries of this fund depend on it to make ends meet.

“I've had more than one person tell me that if the blind pension really were to be taken away, they would simply go bankrupt,” said Gary Wunder, president of the Columbia Chapter of the Federation of the Blind.

According to Baylee Watts, the deputy director of communications at Missouri Department of Social Services, the fund had $49.5 million in its account as of July 23, and had a budget of $37 million for 2024, which means that a $400,000 loss is less than 1% of the total fund.

Eugene Coulter is the vice president of the Columbia Chapter of the Federation of the Blind and the liaison to the Blind Pension Fund. He said that while the financial losses from Amendment 1 will be relatively small, other property tax cuts could reduce contributions to the fund, and the losses would begin to add up.

“Maybe they do another tax to help veterans. I'm not opposed to veterans by any means, but they'll figure out some other method to take more money out of the (fund), and eventually, the benefits will start going down hurting the very people that the pension is designed to help,” Coulter said.

Katz feels that there are alternative solutions to the issue rather than cutting property tax contributions to the Blind Pension Fund to help child care facilities.

“Moving existing money from one social program to another is literally robbing Peter to pay Paul,” Katz said. “(It’s) moving (money) from one social good to another social good instead of increasing the amount we're spending on those social programs.”

Katz said this is emblematic of the legislature's general feeling on funding social programs. He said that politicians in Missouri, especially conservative politicians, chafe at putting money into social programs.

“Putting money into social programs is a difficult sell,” Katz said.

Prevo from Tiger Tots feels that providing property tax exemptions to child care facilities is similar to existing tax exemptions for public schools. He feels enrollment in early education programs can have long-lasting benefits in the children’s lives.

“(If they) understand their 'ABCs' or their '123s' or God forbid they’re learning things like five different languages and how to think for themselves, you find students that are more prepared to be in the learning environment,” Prevo said.

Looking forward

Arteaga hopes this amendment prompts additional legislative attention on addressing the child care shortage.

“I think this is an opportunity for the state to think more broadly about child care deserts,” Arteaga said.

Katz feels that there could be a natural partnership between business and government in addressing Missouri’s child care deserts, since the current shortage of care providers has a detrimental economic impact on the state.

“There are so many businesses that have employees who have children, and their ability to work is limited by their ability to find affordable child care that I think it's possible to get a lot of businesses to step up and collaborate with government,” Katz said.

Other states have implemented solutions that involve partnerships between the private and public sectors. For example, Michigan implemented a Tri-Share program, which shares the cost of child care services between employees with children, employers and the state.

In 2023, Texas implemented a measure similar to Amendment 1 that exempted child care facilities from paying property taxes.

Amanda Coleman, at Community Partnership of the Ozarks, said that organizations across the state are pushing for a similar program called Community Child Care Exchange.

“We need local businesses to get involved with some of the solution-focused ideas on how they can help support their employees,” Coleman said.

For now, it’s up to Missourians to decide whether they want to hand Amendment 1 over to the legislature to determine whether childcare providers should be exempt from property taxes, and who would be eligible.

The primary election is on August 6.

Copyright 2024 KBIA