When Uhunoma Amayo found out his science experiment was one of just 34 selected to be carried out this spring on the International Space Station, he was shocked.

"They pulled me out of class," says Amayo, a seventh-grader at Coronado Middle School in Kansas City, Kansas. "I was dumbfounded."

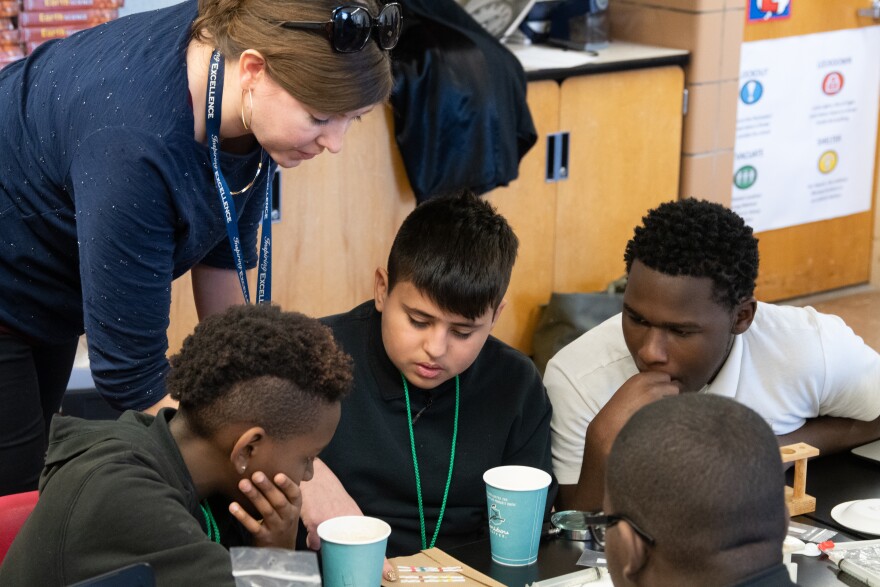

Amayo is one of four students at Coronado who designed the experiment, which will explore whether mint grows as well in orbit as it does here on earth.

"During our research we found that mint is really good for calming and just soothing the body," says Amayo. "So we proposed mint for the benefit of the astronauts."

Their proposal was good enough to be included in the Student Spaceflight Experiments Program, sponsored by the National Center for Earth and Space Science Education and the Arthur C. Clarke Institute for Space Education. The program has facilitated 13 missions to deliver student experiments to be carried out in low-Earth orbit.

This is the first time a school in Kansas City, Kansas, has been selected for the program.

"It was difficult in some parts that we thought we couldn't win," says Carlos Jimenez Reyes, an eighth-grader who worked on the proposal with Amayo, DaQuon Cheadle and Daleshone Sharkey. "I did have my doubts."

That skepticism can be handy when working in the scientific realm, but the demands of the proposal and selection process pushed the bounds of their abilities, says Erin Morley, the boys' science teacher.

"The type of proposal honestly was above probably anything that 13-, 14-year-olds have ever had to do," she says, noting the granular specificity demanded by the selection committee.

"They would ask us to be more specific about scientific names, about what, specifically, every single step would be in the process — from the moment that it would enter the space station," says Morley. "It was very, very intense."

The experiment will take place inside of a long plastic tube, where mint seeds in a plant gel solution will (hopefully) sprout into tiny mint plants.

"In our research, we found out that mint can grow with little to no sunlight," which could make it great for growing in space, says Jimenez Reyes.

The plant gel helps give any potential roots a direction in which to grow, adds Amayo, "because in micro-gravity everything flies everywhere."

After six weeks, the experiment will be carried back to Earth, and back to Coronado Middle School, where Amayo, Jimenez Reyes, Cheadle and Sharkey will analyze their results.

The uncertainty, the challenge and the rigor of the whole process, which was done mostly after school hours and over winter break, has helped change the way Jimenez Reyes thinks about science.

"My opinion on science was more strict and not as fun," he says. "But after seeing this I thought maybe it opens up opportunities for me."

Even Amayo, who has no plans to pursue a STEM career, admits he got something out of the experience.

"The way I view it is like, science is cool," he says. "Just not for me, you know?"

Amayo, Jimenez Reyes and Morley spoke with Steve Kraske on a recent episode of KCUR's Up To Date. Listen to the entire conversation here.

Luke X. Martin is associate producer of KCUR's Up To Date. Contact him at luke@kcur.org or on Twitter, @lukexmartin.