Once a week, Waynesville High School in south-central Missouri resounds with the celebratory air of a football game. The marching band has just completed a lap of the hallways, blaring the school’s theme song, “Eye of the Tiger.”

This school rocks with spirit, even though most of its 1,500 students didn’t grow up in Waynesville, and most of them won’t be staying long.

“As someone who's spent half of their high school years at another place, it’s honestly like, great. I love it here,” said Riley Wright, an eleventh-grader.

Waynesville High School sits just a few miles from Fort Leonard Wood, a military training base on the edge of the Missouri Ozarks. Three-fourths of the students in the Waynesville School District come from military families. For them, moving is a way of life.

Student transiency is increasingly recognized as a disruptive factor in urban schools around Kansas City. But the Waynesville district, which serves 6,000 students, has organized its work around making new arrivals welcome and successful.

Hard to fail

Riley, whose father is a U.S. Army police officer, has attended 10 schools in five states. When he arrived in Waynesville at the start of this school year, he quickly found a spot on the soccer team. Scheduling classes went well, too. Riley, who aspires to be a teacher, says math is his weak spot. He’d passed Algebra I at his old school, but he was worried he wasn’t prepared for Algebra II. So he was relieved when he learned Waynesville had just the class for him – algebra one and a half.

“It’s kind of hard to even fail a class here because everyone’s just very involved and is there for you,” Riley said.

New students are assigned to teacher Denise Taylor’s homeroom for what Waynesville calls “Tiger Time.” She gets about 20 new students a month, and they stay with her for a few weeks until they feel comfortable at the school.

“We do some presentations, talk about policies in the school,” Taylor said. “One day we would talk about what kinds of ideas are out there for our career center. Another day they may be just playing cards, getting to know each other and making friends.”

When students feel ready to leave Taylor’s homeroom, school counselors ask if they have a friend whose homeroom they’d like to join to make that transition easier.

Students helping students

Every school in the Waynesville district has a “student-to-student’ program. Students take newcomers on building tours, give them the inside scoop about policies such as cell phone use and stick with them during that most perilous time of the day – the lunch hour.

“What made me feel welcome was how they showed us around the school and brought us to our classes,” said sixth-grader Krista McDonald, who has already attended schools in Texas, Germany and Japan. She wanted to become a student ambassador so she could take new students on the same tour.

Newcomers also get a supportive reception from teachers, who are trained to assess their academic levels and get them into the flow of class work. And students have ready access to counselors, including one at each school who is paid by the military to support military families.

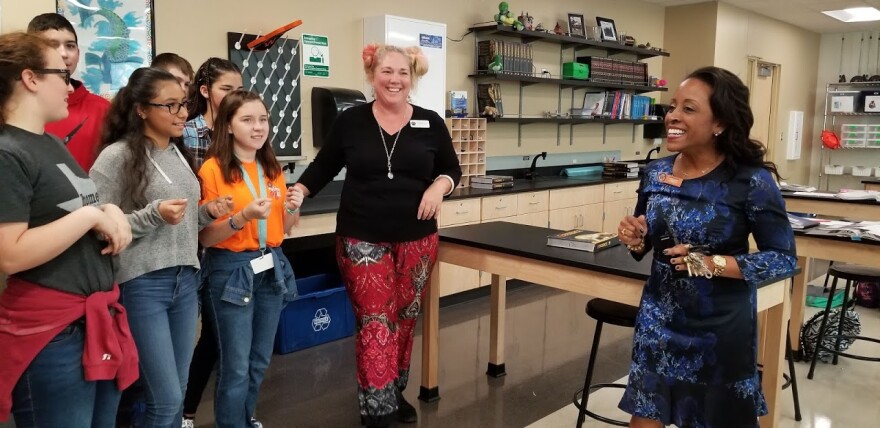

Waynesville Middle School Principal Michele Sumter is married to an Army lieutenant colonel. Her family has moved nine times in 20 years.

“My own three children have probably been in more than 10 schools, and I understand how resilient military kids are in general,” she said. “But I also understand how painful it can be to move around and not be able to have a connection to someone, whether it be a teacher or another student.”

Sometimes that connection is Sumter herself.

“We have a new student today,” she said. “She’s from Texas. I met her this morning walking through the hall with her guidance aide, and we got a chance to talk a little. I told her ‘I'm military, and I know what it's like to move.’ And we instantly smiled at each other, and we understood one another.”

Sumter tells new parents to expect children to struggle academically the first month or so.

“One thing about Waynesville is our coursework is harder than most places the kids have been,” she said.

But Sumter says parents appreciate Waynesville’s rigorous standards.

“You will often find that with military families, we are very particular about the schools we place our students, our children in. And so we go out of our way to live in certain locations to ensure that our kids get a quality education.”

Look to the military?

About a third of Waynesville’s students come or go every school year. While some districts in and around Kansas City see even more transience, that’s still a lot of change taking place. Yet Waynesville’s students perform well on assessment tests – the district is usually right around the state average and well ahead of neighboring rural districts.

Waynesville’s success seems to counteract the narrative that frequent student moves are destructive to achievement. But while urban districts are often told to “look to the military” for tips on how to handle disruptions caused by students switching schools mid-year, the two sectors are worlds apart.

“One of the advantages that I think we clearly have over more of the urban areas would be that while our kids are mobile, our parents are engaged,” said Waynesville School District Superintendent Brian Henry.

That’s not meant as a slam on parents elsewhere. Henry worked in the Park Hill School District before taking the top spot in Waynesville, so he is familiar with the Kansas City area. He knows how hard it is for children to learn when their families are on the verge of homelessness because they can’t pay their rent or find a stable place to live.

The achievement gaps Henry deals with in Waynesville have more to do with different learning standards and schedules in all the states and countries where kids have lived. While Waynesville students bring a fascinating range of experiences to rural Missouri, their schools must still meet state assessment standards.

“When kids come to us, they have a multitude of different experiences that may not align to Missouri standards,” Henry said. “Our classroom teachers, in my humble opinion, are the best in the entire state because they're able to work with that range of learners.”

While educators in urban districts often feel like they’re on their own, Waynesville gets lots of help. At Fort Leonard Wood, military units work with every school in the district. They’re called Partners in Education – or, as they’re known around the schools, “PIE Partners.”

“I use my PIE partners for health screenings,” Sumter said. “The nurse teaches them how to administer the hearing screening, the vision screening and so forth. They help us manage dances, they can come in and tutor. Their partnership is vital to the success of the activities in our buildings.”

The program was conceived by a general at Fort Leonard Wood, who recognized that the success of the base was linked to a thriving nearby school district. More than a third of respondents in a recent Military Times survey said unhappiness over their children’s schooling was a significant factor in their decision to leave active duty.

“Soldiers want a good education for their kids. They deserve that,” Henry said. “They’re giving their lives in some cases to protect our freedoms. So we see ourselves as a key piece of overall readiness.”

The language of resilience

Military-connected schools hold another advantage over places where students move around a lot because of poverty – the luxury of planning. The average length of stay for a military student in Waynesville is two to three years. And when families depart, they usually have weeks, if not months, to prepare to relocate.

But when Robert Bartman was superintendent of the Center School District in south Kansas City, kids would be in class one day and gone the next, forced from their homes by crises like evictions or domestic violence. Bartman, a former Missouri education commissioner and also a retired Marine captain, said those abrupt moves are much harder for students and schools.

“The kids are traumatized,” he said. “Some of them change schools two or three or even four times in a year. They throw their hands up and they don't feel connected to any one school. And when they don't feel connected, that creates not only a learning problem, but it can in some instances creates discipline problems.”

School counselors can help kids process those emotions, but most schools aren’t able to hire as many counselors as Waynesville.

Ruth Ponce-Batts is a military spouse and the counselor at Partridge, one of three Waynesville elementary schools on the Fort Leonard Wood base. She says she and her students share a common language: resilience.

“We talk about how to take on challenges and how to adapt when challenges are presented throughout their lives,” she said. “I really try to teach them those types of social skills, that while we don’t have control over everything, we do have control over ourselves.”

Ponce-Batts used to work in a school where kids moved frequently because their families were poor. She thinks resiliency training works in that setting as well.

“I tell them, ‘Look at all the challenges you've already overcome,’” she said. “Yes, your parent got evicted, but we found another place and now we’ve just got to get more resources for you and try to find food for you.’”

But even if urban schools teach resilience – which many already do – someone has to provide those extra resources. The military has enabled Waynesville to build a sturdy infrastructure to support students as they come and go.

That infrastructure is lacking in urban schools where the moves are more sudden, more frequent and more challenging. To build it, Kansas City schools are going to need a lot of outside help.

Barbara Shelly is a freelance contributor for KCUR 89.3. You can reach her on Twitter @bshelly.

Elle Moxley covers education for KCUR 89.3. You can reach her on Twitter @ellemoxley.