If you can smell what the Rock is cooking, you might be interested in the wine "Niles Plonk" is fermenting.

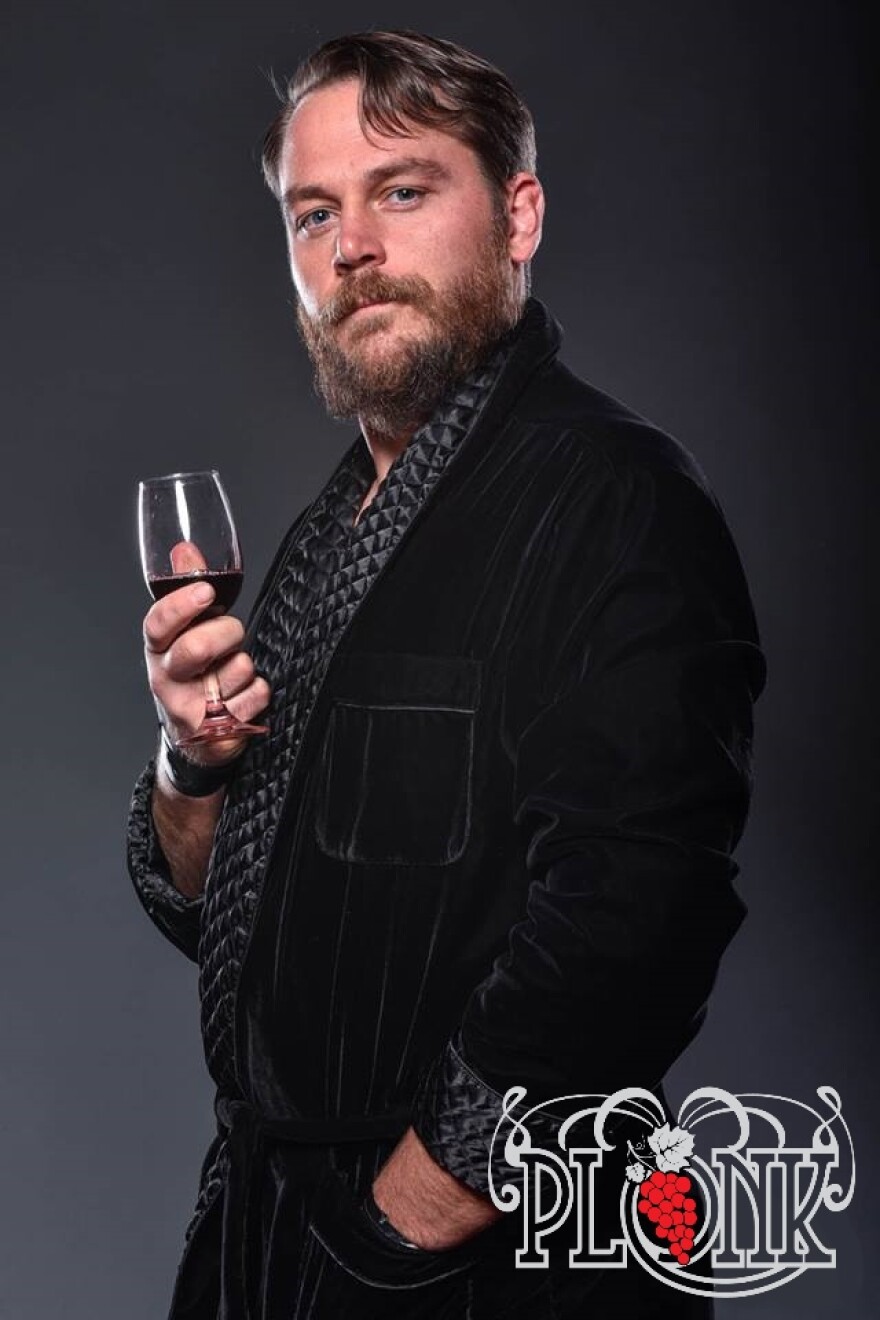

Kraig Keesaman, who owns Windy Wine Company in Osborn, Missouri, wrestles with the newly formed Journey Pro KC as a nasty wine snob named Niles Plonk (Plonké when he puts on airs).

"He's every personification of what you think a wine snob is in every negative aspect of that. It's great because I can take my real-life job and apply it to him," says Keesaman. "In wrestling, your character is really an amplification of yourself."

He describes professional wrestling as an entertainment sport or athletic theater. It's also typically a good-versus-evil proposition — audiences will take that story any way they can get it.

Fans leave no doubt that Keesaman's wine-snob character, who wears a silk robe and carries a glass of wine, is the bad guy, booing and yelling "wino" and "heel" at him.

"We're beer country here," Keesaman says. "Wine is one of those things that, although it's becoming more acceptable in this culture, it's still considered a hoity-toit thing."

He has been wrestling since he was 17, when every wrestler’s goal was to make it to the WWE (World Wrestling Entertainment), which went by WWF (World Wrestling Federation) until 2002.

Now, a resurgence of the independent wrestling circuit makes the WWE a little less appealing.

Journey Pro KC is an independent professional wrestling organization that started in Kansas City in December, taking over for the defunct National Wrasslin’ League.

Co-owner Walter Fulbright says that the business is attracting 25- to-40-year-olds who might have enjoyed watching WWE when they were younger.

He says the shows offer a "mutual catharsis" between performers and fans.

Fulbright's take on wrestling is that it's a combination of athletics, sports, performance art and improvisational theater. The wrestlers play to the mood and whims of each crowd.

"I think people who watch wrestling assume, 'OK, they know exactly how this is going to go from the very beginning when the bell rings. They've memorized it like a circus would; they know the whole act.'"

Not so, Fulbright says.

"What makes this so powerful is that the audience becomes part of the performance, and there are very few arts where that's true."

Keesaman says it's no secret that wrestlers do have an idea of the storyline they'll follow, but a lot more than audience response can change the story. Any variation to the routine causes the performers to improvise.

Maybe the rope someone is supposed to bounce off of breaks. Or maybe the good guy is legitimately knocked out — it is an intense contact sport, after all. How will the bad guy finish the show properly if his partner is unconscious?

It's the element of improv, Keesaman says, that makes wrestling "so organic, and so great for the audience to see and the wrestlers too."

Fulbright says it's a singular type of performance.

"It's a great American tradition that has survived the test of time. It changes over time and reflects who we are culturally as a people, and it's something that connects us."

Kraig Keesaman and Walter Fulbright spoke with KCUR on a recent edition of Central Standard. Listen to the full conversation here.

Follow KCUR contributor Anne Kniggendorf on Twitter, @annekniggendorf.