Anyone who has been to Kansas City's Country Club Plaza has likely seen the work of Arthur Kraft, who sculpted the trio of bronze penguins near the corner of Pennsylvania and Jefferson streets. Even though his name has largely been lost to history, his work is still all over town.

Some Kansas Citians who do remember Kraft's significance argue that he should be as well known as the famous hometown painter Thomas Hart Benton.

“In the 1940s (he was) making these amazing paintings and getting international recognition for them," says Isaac Kostrow, who has been collecting works by Kraft for the past eight years. "But he was still ours. He was still a Kansas City artist.”

By all accounts, in his early days Kraft was headed for greatness. By age 13, he was selling his work at the Plaza Art Fair. His studies at Yale University's School of Fine Arts were interrupted by World War II, when he served with the Army Air Forces. But by the late 1940s, he’d had a one-man show at the Salon de Jean Cocteau in Paris. And he showed his work at The Whitney Museum of American Art, alongside iconic artists such as Robert Motherwell, Willem DeKooning and Georgia O’Keeffe.

Several area museums still have examples of Arthur Kraft’s work. The Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art and The Glore Psychiatric Museum in St. Joseph, Mo., have original paintings on permanent display; the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art has a painting from 1942 titled "Paganini," though it's currently not on view. Far more of his works hang in private homes.

“In the '50s and '60s everybody thought he was going to really be on top of the world and then it just went downhill,” says DeeDee Willson Adams, who knew Kraft through her mother, who was lifelong friends with him. “Being a child, he was just another playmate," Adams remembers. "He was just so incredibly fun.”

Adams says something happened to Arthur Kraft.

Some say it was the war years that changed him. Or the pressures of living as a closeted gay man in the Midwest. Others say it was an assault during a robbery in 1959. Whatever it was, he began to drink heavily.

Kraft spent several stints in hospitals as he battled his addiction. In 1971, he turned a five-week stay in the alcoholic ward at St. Joseph State Hospital into a book, compiling his observations and drawings of fellow patients into the limited edition "Sounds of Fury."

"It was the most wonderful characters he became friends with," says Adams. "His writing was gorgeous. Some of it's deep and some of it's just funny."

One story involved a patient who had apparently burned down his house.

Alf was sent away and on weekends the attendants build him a colorful bonfire with many fireworks to delight his eyes. He seems to be very happy in this new home. No one visits him but the walls are colorful and the padding is fireproof.

Kraft was surrounded by people who cared about him and tried to help him. Through it all, he never stopped making art.

“When he fell on hard times, you know, because he ended up becoming an alcoholic, the people back here, I think, they kind of helped him through that rough patch in his life,” says Reed Anderson, assistant professor of art history at the Kansas City Art Institute.

When he died in 1977, friends described Kraft as “overly generous.” It’s true: He was notoriously bad with money and often gave his work away. He famously forgot the name of the Swiss Bank where he’d placed the money he’d made from selling paintings in Europe. And after he spent two years working on a series of stained glass windows for Overland Park Christian Church, Kraft gave the windows to the congregation without charging a penny.

He had murals and stained glass windows all over the city, but many have been lost, such as his final work at the Veterans Hospital in Topeka. And those that still exist are not well-preserved.

Just behind the Sprint Center at 12th and McGee is a colorful mosaic, with thousands of colored glass pieces depicting a parade of circus animals led by a girl riding an ostrich. There’s an elephant, a giraffe, a horse and even a kangaroo.

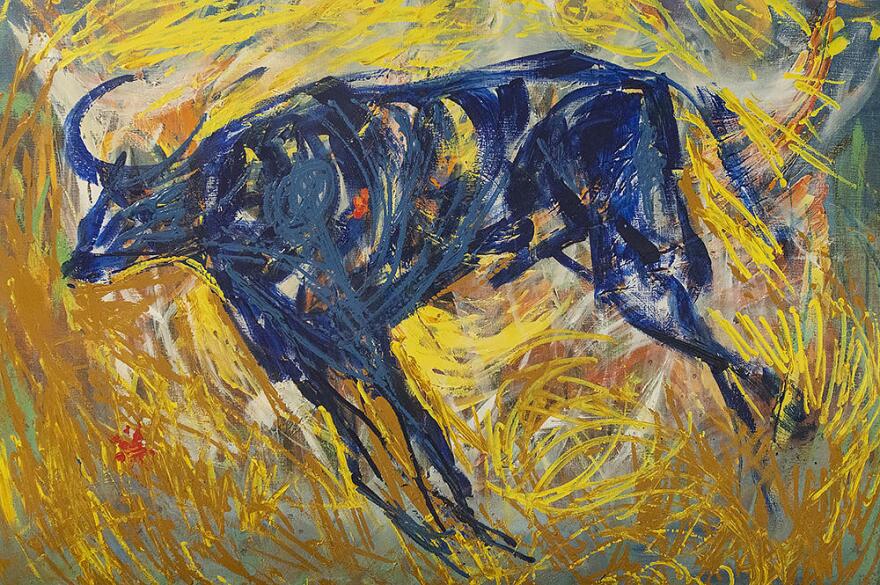

“He was one of those people who liked bright colors," says Anderson. "He liked a little bit of bling. He tended to work with a rather bright, highly saturated color palette, pretty much throughout his entire career. ”

The mural behind the Sprint Center used to be the entrance to the Children’s Library at the Kansas City Public Library. When it was first installed in 1960, Skylines Magazine gave it a craftsmanship award. But today the mosaic is neglected, and two large cracks in the wall have caused pieces to fall out. Despite the damage it still impresses, but it’s in serious need of restoration.

Megan Wyeth has vivid memories of Arthur Kraft’s bright colors, too. When Wyeth was seven, her parents commissioned two paintings from Kraft for a new family room. One was a siren on the rocks, the other depicted a boy riding a dolphin.

“They were both the most beautiful blue that I had ever seen and it really affected me," Wyeth says. "I had never seen the ocean and I remember at that point wanting to see the ocean. When I saw the ocean, it really wasn’t that color. Arthur’s ocean was much richer.”

Wyeth, who's a photographer, used to visit Kraft when he was working.

“Arthur really inspired me to become an artist," she says. "I remember being in his apartment and Arthur showing me how you put paint on a brush and how you put color next to color and talking to me about color."

Although Kansas City art collectors hung Arthur Kraft paintings in their homes next to Thomas Hart Benton’s, Wyeth says there was one big difference: Benton had a manager. Benton's wife Rita was known as a formidable businesswoman.

“One time my parents bought a piece from Thomas Hart Benton and Thomas gave it to them. They brought it home and Rita called and said she wanted the frame back," Wyeth says with a laugh. "So my parents had to take the frame off and drive it back to Kansas City.”

Fortunately, a new generation of collectors such as Kostrow have become interested in the work Kraft left behind.

Kostrow runs a website where people can see and purchase Kraft's work. He’s scoured online auctions searching for articles and exhibition catalogues featuring the artist.

He was just out of college when he saw two Kraft paintings at an auction. Kostrow couldn’t afford them at the time, but he was intrigued so he started to do some research. Now, Kostrow says, he is on the hunt to find Kraft’s work and save it whenever he can.

“What drives me as a collector is just to find the next thing out there and see what amazing work that he might have done that has recently been uncovered,” Kostrow says.

Two years ago, the Westport Historical Society rescued one of Kraft's murals from a bank scheduled for demolition at Westport Road and Broadway. It's in storage now, while members of the organization search for a suitable home for it.

Arthur Kraft is buried at Calvary Cemetery on Troost. On his gravestone, Kraft’s final message reads: “Goodbye for now, I’ll be back that is, if I am not already.”

Julie Denesha is a freelance photographer and reporter for KCUR. Follow her on Twitter, @juliedenesha.

This article was written with research support from the Spencer Art Reference Library’s Artists’ File Initiative at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.