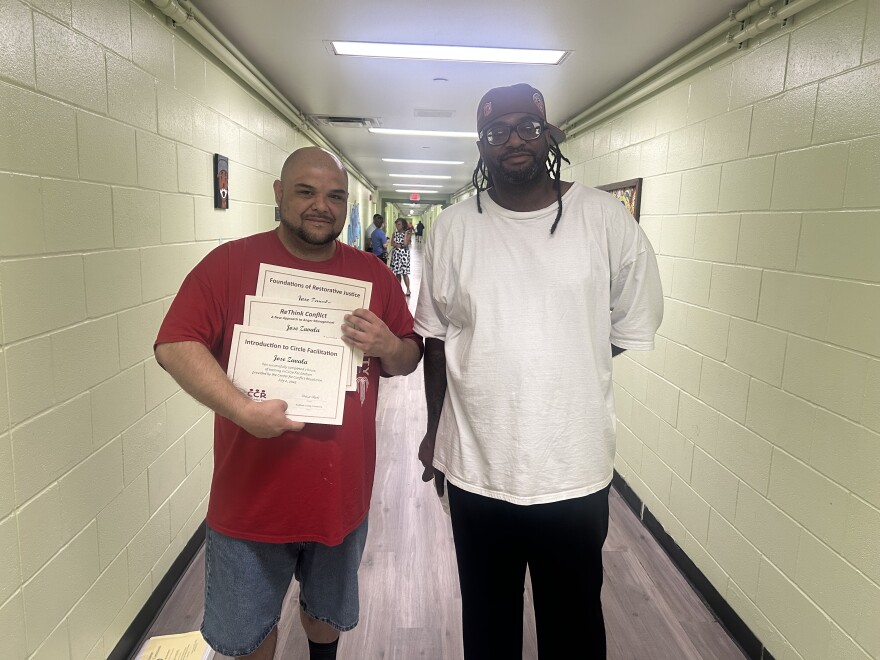

Inside of a former minimum prison facility, men are walking up and down light green, cinder-block hallways. Among them are 40-year-old Jose Zavala and his friend, 45-year-old Doyle Brown. Brown said the two didn’t hit it off when they first met.

“I wanted to beat this guy up,” said Brown, who was released after an 18-month sentence for a parole violation.

“Yeah, we did not get along at first,” said Zavala, a native of Compton, California, who’s served sentences in California, Iowa and now Missouri.

Zavala and Brown are formerly incarcerated men who are now “residents” of the Transition Center Kansas City, a live-in facility for men who are deemed eligible to live in a minimum-security environment as they forge a path toward reentry into society.

Part of the Center for Conflict Resolution, the goal of the Transition Center is to lower Missouri’s recidivism rate by preparing offenders with skills to help them succeed on the outside.

Zavala has served five prison terms. He’s been in and out of eight different facilities.

“My criminal record it's a little bit overwhelming," he said. “I'm a 118-time felon. That's when I lost count. It’s a little bit embarrassing.”

Both men agree they’ve had anger issues, but with each other, at least, have put their grievances aside.

They’ve been taking classes in anger management at the Transition Center, one of the many therapeutic and self-improvement programs residents take while they are there. The curriculum goes in phases.

“Phase two requires a lot of classes,” said Zavala, proudly flashing his certificates of completion. “One of them is core problem resolution, which shows you how to resolve problems without police officers or a physical altercation.”

Zavala has also been focused on career development, hoping to build on his previous experience working in restaurants. His goal is to be the person in charge one day.

“I'm trying to get my food handling certificate, serve certification, my management certification,” Zavala said. “I'm trying to get my hospitality certification as well, so I can become a general manager at a restaurant.”

A measure of success

The MOST Policy Initiative, a nonprofit that bridges different kinds of science and policy, reported that in 2024, the three-year recidivism rate for those formerly incarcerated in Missouri was 35%.

TCKC wants to lower that percentage. Their staff coach residents over the course of four to six months in four phases: orientation, discovery, journey, and finally, transition. The phases include classes on conflict resolution, financial management, wellness, job readiness and more.

The Missouri Department of Corrections recommends inmates to the program. Some are returning TCKC residents, coming back after reincarceration.

The center has only been open since 2021, so officials say it’s too early to have a reliable record of how well residents do long term. If they're keeping offenders out of prison for good.

But since opening, the 150-bed facility has had 463 individuals go through the program. As of summer of 2025, 44% of the residents had successfully completed the program.

TCKC Superintendent Michelle Tippie would like that number to be higher, but each resident has special circumstances that can get in the way of graduation.

“Some of the residents still run into, ‘They ran my criminal history, and they saw my conviction, and they fired me,’” said Tippie. “Or ‘I can't move to this place that I want to because of my criminal history.’”

Not only that, but some of the residents have preexisting issues that are revealed after a resident starts the program. They typically center around substance abuse and mental health, services outside the realm of the center’s expertise.

“A lot of times we find that people who come here may have one of those emerging issues that we're not equipped to deal with,” explained Gregory Winship, a Restorative Justice Strategist for the Center of Conflict Resolution. “And so they may not successfully complete the program. But hopefully we've been able to refer them to another agency or another place where they can meet those needs”

European influences

The TCKC program is modeled off of prison management and reform techniques in European countries, Winship said.

“In 2019, we had a warden from the largest prison in Germany come over and spend some time with us,” he said. “We took three of those principles from Germany, from Sweden, from Norway. A principle of normalization that says life inside the prison should be as normal as possible to life on the outside.”

For example, they tried to make the physical space feel less institutional. The hallways feel more like a school than a prison. There are bright drawings on some of the walls, which do not reflect a bland prison grey.

“The color you will notice (of the hallway) is green,” said Tippie.“ We did a lot of research on calming…and what colors (create it). We wanted this place to not feel like a prison.”

There are classrooms with computers and chalkboards. One wall has a three-paneled bulletin board lined with dozens of small square notes that contain compliments and words of support for fellow residents.

Residents are allowed to work off campus. TCKC provides transportation to get them there.

From her office on the top floor, Tippie oversees the coming and going and the day-to-day operations. Winship has an office just below. His door is always open for residents to air their grievances or discuss challenges in their courses.

Winship and Tippie do everything they can to make sure residents get what they need to reenter society, even if that means referring them to other programs. But Winship said staff gets positive feedback, regardless of some insurmountable barriers for TCKC.

“They all say this program is giving them the skills that they need to be able to get out and eventually stay out,” said Winship. “So, yes, it takes longer than they want sometimes, but they realize that that's the best way for them to be successful.”

'I got grandkids now'

Following a group therapy session, Zavala and Brown go their separate ways. Both men say they’re committed to finishing the TCKC program. Brown said he’s going to complete the program for the sake of his family.

“This place has prepared me and I know what I'm facing,” said Brown. “I don't want to go back (to prison) anymore. I got grandkids now, so all I'm trying to do is stay in a positive mind frame.”

Zavala wants to complete his education, something he never did while cycling in and out of correctional facilities.

“I struggled with my education my whole life,” he said. “I barely learned how to read until about a year ago. When I educated myself, a weight got lifted, the anger was gone. I no longer wanted to fight.”

Another inspiration – the friendly wager Zavala has made with his son. They have a bet that Zavala will get his GED before his son graduates high school in 2027.

“I'm not going to let that guy put me down, or not put me down but rub it in, you know.”