When we think of the civil rights debate in the context of the Kansas City area, we tend to remember the landmark Topeka school desegregation case — Brown v. Board of Education.

But another local civil rights case also was significant in the struggle for racial equality. It was first filed in 1951 and aimed to desegregate the Swope Park swimming pool. The case eventually overturned the "separate but equal" doctrine for the two main public pools in the city, just months before the Brown v. Board of Education decision.

Kansas City and its Park Board justified the whites-only policy at Swope Park by arguing African-Americans had just as nice a pool at Paseo Park. That pool was at 17th and Paseo, where the Gregg/Klice Community Center is today. It was in the heart of the bustling black community just northeast of 18th and Vine.

Clarence Shirley, 83, was a lifeguard at both the Paseo and Swope Park pools.

After walking around the site of where the Paseo pool once was, Shirley sits on a bench and recalls how packed it got every summer.

"If you’d been in [the water] you had to stay out for 30 minutes so other kids could have a chance to swim," Shirley says. "We'd go through the line and check to see if your suit was still wet. If it was, you weren't allowed back in."

Rhonda Smith may have been in one of those lines.

She fondly remembers long, hot summer days at the Paseo pool. She and her friends would leave their homes around 8 a.m. They wanted to get there early because at noon it cost a quarter to get in. She says they'd pack a lunch and stay until 3 p.m.

Smith says African-Americans couldn't live south of 27th Street at that time. Even if Swope Park were open to her for swimming, she says her mama would never let her go all the way to 63rd St. alone.

"I didn’t know any better," Smith says. "We were just happy as ever because at least we did have a place to go and play. "

The lawsuit

It was this kind of complacency that lawyers challenged in the case of Esther Williams et.al v. Kansas City, et.al. The local NAACP helped three young African-Americans - Esther Williams, Joseph Moore and Lena Smith - sue the city. The suit claimed the plaintiffs were denied their 14th Amendment rights to equal protection under the law when they were denied tickets to swim in the city’s public pool at Swope Park.

Howard Sachs, now a senior U.S. District Judge himself, was a clerk for Judge Albert Ridge who decided the case.

"I don’t know if it was reported outside the KC area very much," Sachs says. "(The case) was important enough that Thurgood Marshall, then chief attorney for NAACP, came in to try the case."

Lawyers for the city, however, filed a motion to have Thurgood Marshall removed from the case.

They cited The House Un-American Activities Committee and its claim that some of Marshall's legal affiliations were "fronts for the Communist Party."

The judge overruled the motion.

Justifying segregation

The primary claim of the city was that everything about the Paseo Park pool was as spacious, well-maintained and serviceable - basically equal - to the pool at Swope Park.

But to bolster its argument, the city claimed segregating whites and blacks was not discrimination, but public safety. Lawyers pointed to the riots in St. Louis after African-Americans were allowed to swim at Fairground Park pool a couple years earlier.

In addition, officials claimed they were preserving a long-observed custom.

“The policy of operating separate swimming pools for the two races,” read court documents from the case, “is reinforced by a recognized natural aversion to physical intimacy inherent in the use of swimming pools by members of races that do not mingle socially.”

The concern extended beyond violence. People worried about interracial sex.

“People were sensitive to the physical aspects of the swimming pools,” Sachs says.

The courts decide

Judge Ridge ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in 1952. The city appealed. The pool was shut down during the appeal process, allegedly to avoid the kind of violence that was occurring around legal battles to desegregate recreational facilities elsewhere in the country.

When the Supreme Court denied the appeal, Ridge ruled in June 1954 that the city's arguments against opening Swope Park pool to all races were not good enough. He wrote that to deny plaintiffs entry to Swope Park pool was “a deprivation of rights, privileges, and the equal protection of the laws secured by the 14th Amendment.”

When Swope Park pool opened to African-Americans

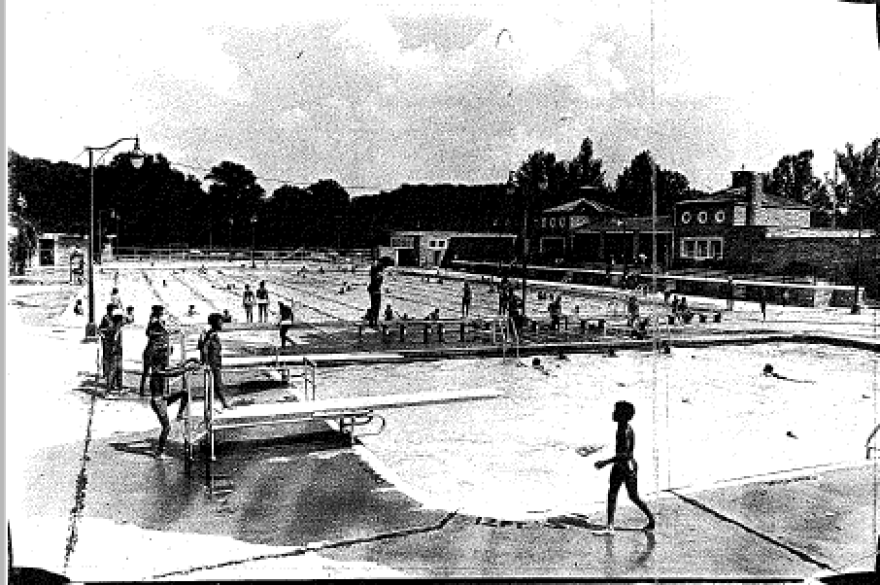

I met Alvin Brooks out at the Swope Park pool on a recent winter day.

Brooks has been a civil rights advocate for decades, Kansas City mayor pro tempore, and a policeman. In the summer of 1954, Brooks was the only African- American in his Kansas City Police Academy graduating class. That summer, the city decided he should patrol at Swope Park pool as the first black swimmers were allowed in.

Gazing through the gate at the empty pool today, Brooks has a distracted look on his face as if he's hearing the voices of swimmers 65 years ago, reliving his patrol around the perimeter of the pool.

He recalls there wasn't any trouble, but the black kids and the white kids didn't mix.

"It was smooth, but it wasn't integrated. Blacks were not here in large numbers," he says. "I think that probably some didn't know they could come out. But the main reason was their parents didn’t let them come. (Their thinking was ) if they didn’t want us then, we don't wanna be there now. "

Over the years, that's changed.

Life long Kansas Citian Susan Lawrence says she vividly recalls right after segregation, she and her family were some of the few white people in the pool.

"It was very crowded with whites and then after the lawsuit they didn’t come," she says. "We didn't have Jim Crow laws, but it was the Jim Crow mentality — and it was in Kansas City. "

Thurgood Marshall, who had such a hand in the Swope Park case went on to argue Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court. That decision struck down the separate but equal doctrine for public education and is widely perceived as the real start to the Civil Rights movement.

But Kansas City's Swope Park pool case was an important step along the way.

65 years later — some might wonder about the impact of the case. If you go to the Swope Park pool this summer, you’ll see mainly African-Americans. It’s now a neighborhood where mostly African-Americans live.

The success of desegregating the Swope Park Pool, like so many desegregation cases, may be as debatable today as it was a generation ago.

Laura Ziegler is the Community Engagement reporter and producer at KCUR 89.3. Reach her at lauraz@kcur.org or on Twitter @laurazig.