Winding 10 miles north and south through the heart of Kansas City, Paseo Boulevard, or "The Paseo," is the longest and one of the oldest boulevards in the city. But before we had The Paseo, and all the other parkways and boulevards that have come to define the city, Kansas City was basically a congested metropolis that was hard to get around.

"There are a lot of things written in the early history of the city that say you know, you couldn't really have picked a more foreboding location for a city," says Daniel Serda, an urban planner with inSITE planning.

By the middle of the 19th century, Kansas City was bustling with commercial activity — and it was growing fast. The steep bluffs and ravines that come with being a river town made it challenging to navigate. There were cable cars like the one that connected the West Bottoms to downtown, but most people were traveling by foot or horse.

In his book "Kansas City And How It Grew," James R. Shortridge cites a few accounts of what it was like coming to Kansas City in the mid 1800s.

He says visitors, "praised the hustle of the people, but bemoaned the crudeness of the site and its buildings." Some visitors complained that it was smoky.

Another visitor in 1871 says she can't imagine, "a more unpleasant" place to spend time.

But, luckily for Kansas City, by the end of 19th century a lot of growing cities were thinking more about roadways and design. And there was a movement to create more green spaces within city landscapes. Cities were looking to New York City's Central Park, designed by landscape architect Frederick Olmsted, as an example of how to beautify a growing urban area.

The City Beautiful movement

German landscape architect George Kessler led the City Beautiful movement in Kansas City. Kessler's philosophy was to incorporate the roads with the natural contours of the land and to show off the bluffs, which he believed to be most scenic parts of the city.

In 1893, Kessler submitted a report giving a comprehensive look at the city's topography, traffic patterns and population growth. This report became the foundation of the parkway and boulevard system.

The Paseo, along with Benton Boulevard, Independence Avenue, Admiral Boulevard, Gladstone Boulevard, Linwood Boulevard, Armour Boulevard and Broadway were to be connecting points for people to travel to and from the different parks. They were designed to be green arteries used for pleasure drives, promoting Kessler's idea that there should be places within cities where people can escape into nature.

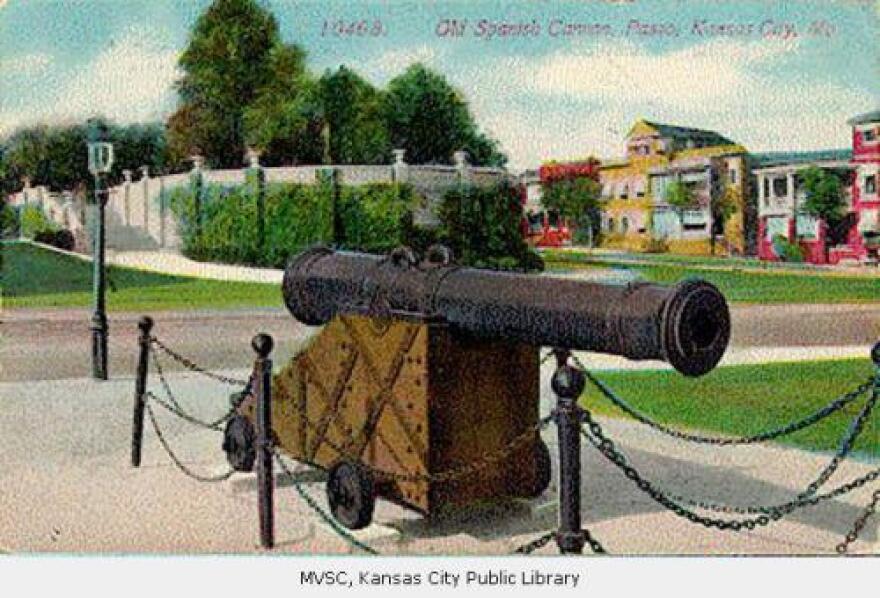

The oldest section of The Paseo, and the first boulevard in Kansas City, stretches from Independence Avenue to 17th Street. It featured a dual boulevard parkway where each side of the road has three lanes of one way traffic, that are divided by a small park as a median. Throughout the beginning of the 20th century The Paseo grew to extend further south, the boulevard section of it eventually reaching 79th St.

"It's a very deliberate reintroduction of that natural topography into the grid," says Serda. That's why it winds the way that it does, and has features like Troost Lake, which serve as a catchment area for rainfall.

So why the name Paseo?

Kessler named Kansas City's first boulevard after Paseo De La Reforma, an iconic road in Mexico City, because it was an example of a grand boulevard in the midst of a major city. It served as an example for something he hoped for the future of Kansas City.

"Part of Kessler's design philosophy was that it was going to be a lasting legacy, an institutional framework as much as a physical framework for direction and providing a vision for how the city was going to grow, really for the rest of its existence," says Serda.

But not everybody was on board at first

Before The Paseo was built, the land around that area was basically a shanty town. The city used eminent domain as a means to acquire the property to develop the boulevard and parkway system.

"They were effectively used as an early form of blight abatement and slum clearance," says Serda.

The new system also received pushback from people in the business community who were reluctant to have the city take on additional powers and have to pay higher taxes.

So part of a compromise was to route boulevards out of business districts and have them serve more as residential connecting points.

Over the years, The Paseo and other boulevards in the original system have seen some changes, with the building of Bruce R. Watkins 71 Highway, and I-70, but a lot of the original historic design elements are still there.

The Paseo today

Kansas City Parks and Recreation Director Mark McHenry says The Paseo's most northern and southern sections are in the midst of some much needed revitalization.

At the southern end of the roadway there is a new flood water management program being led by the Water Services Department in collaboration with the Marlborough neighborhood to address flooding and water flow that runs into the Blue River.

At the north end of the roadway, The Paseo Gateway Project is underway. It's a new plan funded by a grant with the Housing Authority. It will incorporate new housing and will enhance the intersection where The Paseo meets Independence Avenue.

"It's a traffic intersection that's a little dicey right now," says McHenry. "People aren't sure exactly what lane to be in at the right time — things of that nature. So traffic flow is a part of that, also it was starting to look a little shabby."

McHenry says the historic intersection will be redesigned to become a "gateway for the city." The new plans incorporate a sort of roundabout design with a vertical element that will serve as a welcoming point for people entering Kansas City.

Suzanne Hogan is a contributor and announcer at KCUR 89.3.