A high school designed to support teens recovering from substance use disorders is coming to Kansas City.

It’s one of three recovery high schools approved by Missouri’s state board of education on Tuesday. One school would be sponsored by Cape Girardeau Public Schools, and one each in Kansas City and St. Louis would be sponsored by the organization Vivo Missouri.

The recovery schools would be the first of their kind in Missouri, joining more than 40 others operating across the country.

Melissa Mouton, Vivo Missouri’s founder, said families may be struggling for years before enrolling their teen in a recovery school.

“It's nice to be a solution that can turn all that around for a family. It's still messy. There's still ups and downs,” Mouton said. “Nothing is a magic wand, but it provides a source of strength for a lot of families.”

Vivo Kansas City is projected to open in August with 20 students, according to documents presented at Tuesday’s meeting. By the 2029-30 academic year, the school aims to enroll 80 students.

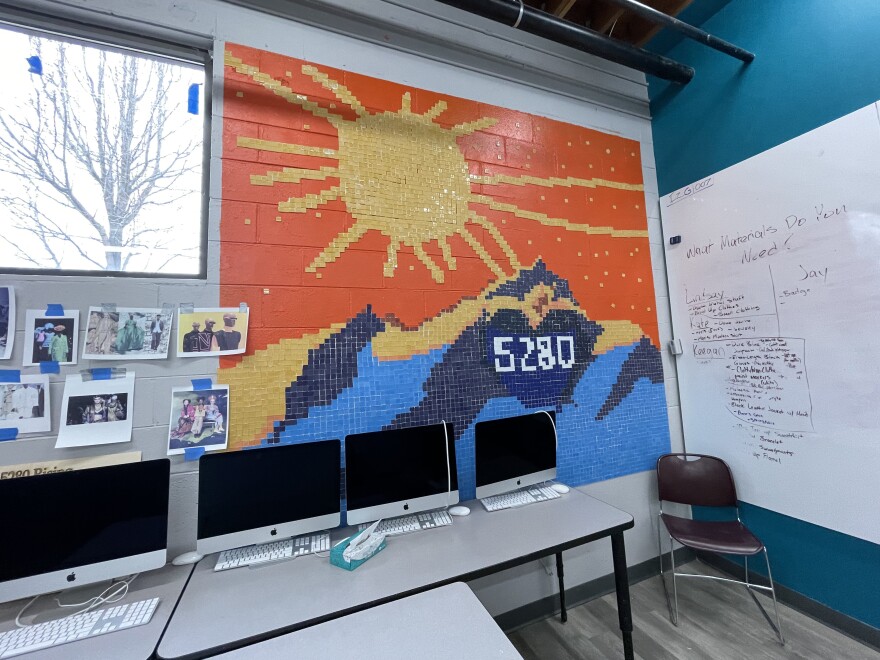

Mouton already has experience running schools for teens in recovery. In 2018, she founded 5280 High School in Denver, and it now supports just over 100 students.

Teens are often anxious about sobriety and worry they won’t have friends, Mouton said. Her schools’ model gives students agency and takes an individualized approach to learning so they can find their passions and pursue them.

“We want to make sure that the academic component is just as stimulating, just as interesting and just as exciting for them as their community in the recovery school,” Mouton said.

Missouri recovery schools are part of a growing trend

Michael Durchslag, board chair for the Association of Recovery Schools, said his group has seen significant growth and interest in recovery high schools across the country.

He said substance use among adolescents is declining, but the severity of use is increasing.

“Even though there might be less young people using, we've seen how they use, what they use, to the degree they use is getting much more acute,” Durchslag said. “So the need is absolutely there.”

He’s also director of P.E.A.S.E. Academy in Minneapolis, one of the longest running recovery high schools in the country. It’s been operating for 36 years; Durchslag said some recovery schools may have opened years earlier, unaware of their counterparts in other states.

He said recovery high schools look a lot like traditional high schools. Students go to class, learn state curriculum and eventually graduate with their diploma.

A big difference is the size. Durchslag said recovery high schools are typically smaller than traditional high schools in part so they can better meet student needs.

The schools also have a greater emphasis on mental health and recovery from substance use disorders. He said best practice is for schools to have peer recovery specialists, licensed alcohol and drug counselors, and trained social workers to support students.

Students attending these schools have frequently already gone through a substance use treatment program and are engaged in their recovery, Durchslag said.

“Oftentimes, they put a lot of work into that, and then they're faced with going back to the same high school, and they really have to almost choose between their recovery or their education,” Durchslag said. “It's not necessarily the schools, but it's really the peers that they are connected with.”

Recovery high schools follow a yearslong effort

Kelli Unnerstall, founder of Aspire Advocates for Behavioral Health, has also been working for years to bring recovery schools to Missouri and the St. Louis region.

Unnerstall said she founded Aspire Advocates to try to improve the behavioral health system after experiencing it herself. She lives with bipolar disorder and got sober when she was 15.

She wishes she’d had access to a recovery high school as a teenager.

“What I tell young people now is the world, the community, individuals, they are showing up for you. Laws are getting passed and money is coming your way. The world sees you,” Unnerstall said. “They see your suffering, they care, and they're willing to act and that's what's happened.”

Passing legislation to open recovery schools in Missouri was an uphill climb. Unnerstall said some public schools were hesitant to start recovery high schools because of concerns about their own expertise, bandwidth and finances.

Mouton said she didn't initially plan to expand her recovery school model to Missouri. Then a few years ago, she connected with Louis Steele, the co-founder of Be Free KC, a local organization that supports people through recovery from substance use disorders.

They worked on legislation to allow recovery schools in Missouri, Mouton said, and decided Mouton could run her own through a nonprofit.

A Missouri law passed last spring allows the state education department, school districts, and magnet, charter or private schools to open a recovery high school. More than $3 million from opioid settlement funds has been allocated to the initiative.

The recovery schools will also receive funding from the school district where a student lives, with the state education department covering the difference. The average cost to educate a student in a recovery school is $7,000 more than their peers in traditional schools, according to state documents.

The schools created through Vivo Missouri are publicly funded and free to attend, but are considered private schools, Mouton said. That’s so they can serve students living across regions of the state, not just in specific school districts.

Some Missouri state board of education members raised concerns this week about the long-term financial sustainability of recovery schools when opioid settlement funding ends, and whether the department would be required to fill the gap.

Durchslag said the average lifespan of a recovery school is about 10 years because of funding and the small size of the schools.

Mouton said the school’s long-term budget will depend on enrollment and can become financially stable at around 120 to 130 students enrolled. If it doesn’t reach those numbers, she said there would be a tuition gap that could be filled by the state education department or additional fundraising.

Missouri Education Commissioner Karla Eslinger said the recovery schools would be subject to annual review and availability of funding from a mix of public and private sources. She said there also may be changes to the legislation limiting how much tuition can cost.

‘Positive peer pressure’

Mouton said her team is close to announcing an address for the Kansas City school. It will be centrally located and will be its permanent site, she said.

She said her favorite part of running a recovery school is when a new family visits. They may be nervous, scared or even hopeless, but that soon changes, she said.

“Within 20 minutes of them arriving at the school, they have just a sense of calm, a sense of possibility,” Mouton said. “I hear things like, ‘Yeah, I want to go here because I could see these people are really cool, these kids are really cool.’”

Jamie Vollmer, Aspire Advocates’ recovery high school project manager, said the key to recovery schools is “positive peer pressure.” When teens who are early in their sobriety attend a recovery school, they have other students who are further along in their journey to look up to.

A study found students attending a recovery high school are more likely to stay sober and graduate than their peers in traditional high schools who have gone through treatment.

“To be able to stop this usage, put this substance use disorder into remission, and give these young people what is proven to work at an age like this, before they launch into adulthood, is just … the lives and families and systems that will change is, is just exciting,” Vollmer said.