A month ago, St. Louis Public Radio reported on the questionable manner in which the state of Missouri got ahold of its potential execution drug. Now Missouri has a new plan to go ahead with two upcoming executions, but the process is anything but open.

On Oct. 11, Gov. Jay Nixon told the Department of Corrections to make a change. He wanted them to come up with a new drug to carry out executions.The drug they’d originally planned to use is a popular medical anesthetic, and using it in an execution could have triggered a shortage in US hospitals.

What’s more, the state obtained the drug from a company that wasn’t authorized to sell it.

“I looked at this from two perspectives: number one was public safety, obviously, and the second was public health," Nixon said, when asked why he asked for the change. "On the public safety side, making sure that we continue to move forward with executions when folks have committed incredibly serious offenses like this, I think is an important public policy matter that I continue to support.”

A week after Nixon asked for a new execution drug, the Department of Corrections came up with one: a drug called pentobarbital. Pentobarbital is a sedative and it's used by veterinarians to euthanized animals.

A Shroud Of Secrecy

But the Department of Corrections didn’t stop with just changing the drug -- they also made another important alteration. They changed the rules to hide the identity of the drug supplier.

It used to be that just the names of the people actually carrying out the execution were confidential. Now the so-called “execution team” includes “Individuals who prescribe, compound, prepare, or otherwise supply the chemicals for use in the lethal injection procedure.”

The American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri has sued, saying that change takes away any public oversight of the process.

“I think the First Amendment gives the public the right to know who the execution team is, and to question whether or not they’re qualified," the group's legal director, Tony Rothert, told us.

He said the new rule is meant to silence debate. "It’s just a shroud of secrecy to try to prevent criticism and skepticism from the public."

Keep in mind that Missouri bought its previous execution drug from someone who wasn’t authorized to sell it. So the state has a questionable track record on this.

One in Five

The one thing we do know is that the state is getting its pentobarbital from something called a compounding pharmacy. Normally, compounding pharmacies are used to prepare a drug that isn’t commercially available to meet the needs of a specific patient.

For example, a doctor could write a prescription for a pharmacy to create a liquid form of a medication for a kid who can’t swallow pills.

That’s the normal use. Missouri is turning to a compounding pharmacy, though, because no drug manufacturer wants its product to be used in a lethal injection.

Using a compounding pharmacy is an issue because the Food and Drug Administration has found problems with the quality of some of the drugs they make. Last year, a contaminated drug made by a compounding pharmacy infected hundreds of people across the country, leading to dozens of deaths.

But the FDA doesn’t regulate compounding pharmacies -- individual states do.

In Missouri, the Board of Pharmacy has found problems on its own. In inspections spanning the last decade, the board found that about one out of every five drugs made by compounding pharmacies failed to meet standards.

A report called the failure rate “high” and “of obvious concern."

"It’s what I would refer to as faith-based medicine," Randy Juhl, the former dean of the University of Pittsburgh's School of Pharmacy said. Juhl once led a committee that advised the FDA on how compounding pharmacies should be regulated.

We asked Juhl what he thought about a compounding pharmacy making a drug to put someone to death.

“I question whether that practice is even legal, given the pharmacy practice act of your state, and the DEA regulations," Juhl said.

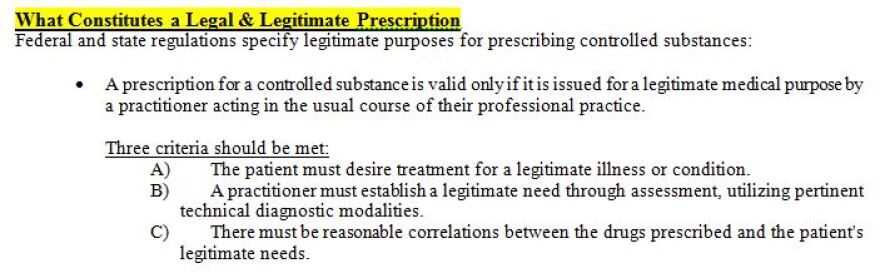

In order to dispense a drug like pentobarbital in Missouri, a pharmacist needs a prescription for a specific patient for a legitimate medical use. But what about a pharmacy that sells a drug for lethal injection?

“I don’t know, is this a legitimate medical use?” he asked.

We’ve asked the Missouri Board of Pharmacy about the legality of a compounding pharmacy making a drug to be used in an execution. A spokesperson responded that "Lethal injection is not referenced in state statute regarding compounding pharmacies."

Putting the legality issue aside, we asked Juhl if, in general, he would trust a drug coming from a compounding pharmacy. He told us that it would depend on whether he trusted the pharmacist.

And that’s what’s problematic about Missouri’s situation. Because of the new rule that makes naming the compounding pharmacy illegal, we really can’t know. We can’t verify if the company is registered and licensed properly, we can’t verify if the company has been cited in the past for shoddy practices. Because of the new rule, there is no public oversight of where the execution drugs are coming from.

A lot of people reading could be wondering why we should care whether Missouri is getting its drugs from a reputable source. After all, the inmates set to be executed have been convicted of doing atrocious things. And the state isn’t giving them these drugs to make them well -- it’s doing it to kill them.

"A Sufficient Amount Of Time For Death To Occur"

John Simon is a constitutional lawyer and has been working with the legal team that’s representing Joseph Paul Franklin, who’s set to be executed next week.

Franklin is being put to death for killing a man outside a St. Louis synagogue in 1977 -- and has confessed to killing numerous others.

Here’s what Simon told us could happen if the compounding pharmacy comes up with an execution drug that isn’t strong enough to kill Franklin quickly.

“One scenario will be that he will die a lengthy, excruciating death," Simon said. "And the world will be aghast.”

According to the new execution protocol, if Franklin doesn’t die after the first dose -- which could happen if the drug isn’t potent enough -- the Department of Corrections is supposed to administer another syringe.

But that’s only after quote “a sufficient amount of time for death to occur.” No further definition of how long that actually would be is given. And that could mean a slow and painful death.

“We are better than he is. Criminal penalties aren’t intended to drag us down to the level of the worst offenders," Simon said.

For three weeks, St. Louis Public Radio has been trying to get the Department of Corrections to release documents that would provide some insight into the quality of its execution drugs.

So far, they have delayed, and used the new confidentiality rule to withhold the records we’ve asked for.

You can read all our correspondence with the Department of Corrections here.

The Department of Corrections reports to Nixon. So we asked the Governor if he told them to make the supplier of the execution drug confidential.

“I didn’t," the Governor told us. "The only thing I instructed them was to be sure that we have a protocol, and for them to move forward and get another method. That’s all I said.”

Since the Governor says he did not tell the corrections department to make the supplier confidential, we asked his office if he will tell them to make it public again.

His office didn’t get back to us, and neither did the Department of Corrections. The Missouri Attorney General declined to comment.

Unless there is some legal intervention from one of the numerous lawsuits against the state of Missouri, the Department of Corrections will carry out its first execution with a drug from a compounding pharmacy next week.