A teenager wakes up, gets ready for school. Slips a smartphone into her pocket on the way out the door.

Her day may well include some biology or chemistry, history, algebra, English and Spanish. It likely won’t include lessons on how that smartphone — more powerful than the computers aboard the Apollo moon missions — and its myriad colorful apps actually work.

That worries some Kansas businesses, lawmakers and educators who see a disconnect between what students learn and the technologies that have transformed everything from tractors in wheatfields to checkout lines at grocery stores.

But barriers to change abound. Computer wizzes earn more money programming in C++ than teaching it to teens. And cramming computer science into more students’ schedules could cut into time spent learning about evolution, trigonometry or the laws of physics.

“We’re no longer at a time where we can just continue what we’re doing,” said Rep. Steve Huebert, an engineer who chairs the education committee in the Kansas House.

Think about the needs that that creates for large employers, small employers ... And everybody's ability to continue to grow and thrive. - Anna Hennes, Cerner

Huebert recalls learning chemistry, physics and biology in school. But in the working world, computers proved a critical tool for his job — one that he had to learn on the go and that only grew in importance.

If some students think computer science may better fit their career goals, he wonders, why not let them swap a traditional science class for a chance to learn skills such as programming?

“If we can do that,” he says, “it’ll be a win-win for everyone going forward.”

Talent-hungry companies

Code.org, a tech-company-fueled advocacy group, says most American high schools not only don’t make students take computer science — many don’t even offer it.

The group’s attempts at tracking computer science education nationwide suggest such classes remain particularly rare in Kansas.

Meanwhile, businesses hunger for tech talent. Computer science, they argue, lifts students and economies alike in a world where even the smallest of startups need websites, apps, databases and analytics.

“Think about the needs that that creates for large employers, small employers,” says Anna Hennes, a program manager at one of the region’s highest-profile tech firms, medical record software giant Cerner. “And everybody’s ability to continue to grow and thrive.”

Kansas City alone has added thousands of tech jobs in the past decade, and jobs in that line of work generally pay much better than the average gig.

Right now, though, where students live affects their chances of picking up HTML or other coding knowhow at school.

- Most states let students who take computer science count it as a credit toward graduation.

- That doesn’t help students at high schools without computer science, though. So, a third of states also make sure their schools actually offer it.

- A few states go beyond that, requiring computer science education for all students in high school or even before then.

Kansas doesn’t do any of those things.

In February, the issue landed in the House Education Committee, where Cerner lobbied for a bill to let computer science count as a graduation credit. (The original bill called for mandatory computer science education, but Cerner says that version was a mistake.)

Expect the topic to surface again next year. In the meantime, education officials, lawmakers and businesses are meeting, talking, puzzling through the matter.

Related: Kansas City's Tech Market May Need Coding Skills Enough To Drop The B.S. Degree

But it’s tricky. Right now, high school computer science counts as an elective. Requiring all students to take the subject would put districts in a bind. They’d need the right curriculum, technology and software.

Maybe the bigger question is: Where would all those teachers come from? Schools already struggle to find and keep other specialized teachers, such as those for science and math.

Yet letting students instead count computer science toward core graduation requirements means excusing them from something else. Different states take different approaches. Usually, they let students ditch some math or science. More rarely, students can take programming as a foreign language or other credit.

Either way, professor Perla Weaver says, you’ll upset someone.

“There’s things that we have for decades — if not centuries — assumed are part of basic education,” said Weaver, who heads the computer science department at Johnson County Community College and who used to teach high school.

Maybe you could you make a case that computer science would come in handier for a lot of students than knowing the details of DNA, she said, but “boy, don’t say that in front of science teachers. … It’s an insult.”

Many educators and scientists worry students already don’t get enough math and science, and that the nation’s supply of young scientists and its public understanding of critical concepts such as climate change suffer as a result.

A survey by Yale University, for example, found only about half of Kansans believe humans are driving climate change.

Kansas high schools currently require at least 3 years of math and science each for graduation.

New state guidelines

Kansas has long had standards for math, English and other subjects: guidelines that tell teachers when their students should learn about fractions and persuasive essays.

But when should they understand what a space bar is? How passwords work? The risks of social media and the implications of documenting their daily lives online?

In April, Kansas adopted standards for incorporating computer and internet concepts into student learning at all ages. The Kansas State Board of Education gave the go-ahead after months of educators and computer scientists hammering out details, asking for public input. Tweaking, writing, tweaking again.

Even digital natives need explicit instruction about computers, says Lisa Whallon, a computer programmer turned educator at Olathe Northwest High School.

Students whose thumbs and index fingers fly across the screens of iPhones and iPads to text friends and do homework land in her coding classes hunting and pecking their way across traditional desktop keyboards.

Whallon makes them build the muscle memory needed to type with ease.

“I have adults say to me, ‘Really? Don’t kids know how to type?’” she says. “I feel like we’re doing our children a disservice by thinking that they just learn stuff.”

The new state standards remain effectively voluntary for schools, but educators still consider them a big deal. The guidelines open the door to creating a specialized license for computer science teachers, preparing students at the state’s colleges of education, and training teachers already working in schools.

And they emphasize “computational thinking” — breaking down problems and then seeing and designing solutions as a series of smaller steps.

“People look at computer science and they think it’s just coding,” said Stephen King, who helped develop the standards at the Kansas State Department of Education. “The reality is, it’s far more widespread, far broader than that.”

Whallon’s coding students at Olathe Northwest make flow charts, bounce ideas off each other and brace themselves for bugs in their code.

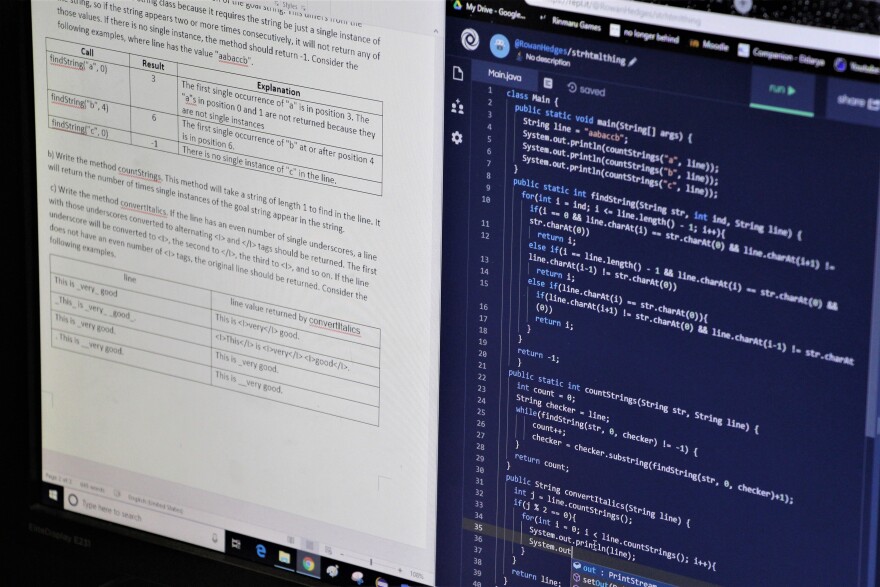

Coding an algorithm for a virtual card game took Eric Zhuo five class periods to write in Java.

“That’s the code that I struggled with the most,” the aspiring computer engineer says. “But when I figured out how to complete it, it was a very good feeling.”

None of this conflicts with science education, says Paul Adams, the dean of education and a professor of physics at Fort Hays State University. Kansas standards for science already ask schools to teach computational thinking through that subject.

But if the goal is for more students to try their hand specifically at coding, Adams would prefer integrating programming concepts into other subjects as a tool, much as scientists use it for their work.

“If you present your research in physics, you present your Python code,” he said, referring to a popular coding language used both to calculate results and share methodology. “It’s what we learn to do our science.”

“To say, well, ‘Don’t worry, we’re going to remove, for example, earth and space science, or we’ll take out a biology’” in school and allow coding instead, “then you’ve lost that whole suite of knowledge.”

Equity in education and careers

Just 10 percent of graduating computer science majors at Kansas colleges in 2017 were women. That ratio seems to hold true in Kansas AP Computer Science classes.

It’s a nationwide problem. Students of color are underrepresented, too. That restricts access to good jobs, says Code.org, and hinders diversity among the people who develop the technologies that serve and shape our world.

“We can’t just have white males creating these things and being involved in these things and knowledgeable about these things,” says Pat Yongpradit, the group’s chief academic officer. “We really need everyone to be knowledgeable and involved in creating the future.”

Rowan Hedges, another of Whallon’s Java students aiming for a tech career, is used to being either the only girl or one of just a few in her programming classes.

“I feel like I have to be better than I am at all times,” she said, “or else I’ll be failing the female population.”

“Even though it’s not a hostile environment,” she said, “it just is intimidating to see a ton of guys who … might have people who encouraged them to do the field throughout their life, just because they’re guys.”

If schools pick up on Kansas’ new computer science guidelines and expose more students to computing earlier, teachers hope it could make more girls and students of color feel at home in the world of code.

If the Kansas State Board of Education takes another step by letting computer science count toward graduation (or if the Legislature forces its hand), that could effect change, too. Code.org says computer programming enrollment seems to become more diverse when states count it toward high school graduation.

Yet this would stop short of making sure all Kansas schools offer coding. Nor would it address the fact that wealthy, suburban schools can find teachers and offer specialized classes more easily than those in poorer, more rural or predominantly black or Hispanic parts of the state.

That’s a serious conundrum, says Rep. Rui Xu, another member of the House education committee. And it has no easy solution.

“If we want everybody to have the same opportunity,” says Xu, “then I don’t know that a voluntary program like this solves that.”

Celia Llopis-Jepsen is a reporter for the Kansas News Service, a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio covering health, education and politics. You can reach her on Twitter @Celia_LJ or email celia (at) kcur (dot) org.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.