The family of a 7-year-old boy who was brutalized and tortured for years and then killed by his father and stepmother has lost its bid to hold Missouri social workers liable for negligence in his abuse and death.

The Missouri Court of Appeals on Tuesday upheld a lower court’s finding that the social workers were entitled to official immunity. That doctrine shields public employees from liability for alleged acts of negligence committed in the performance of discretionary acts while they were on the job.

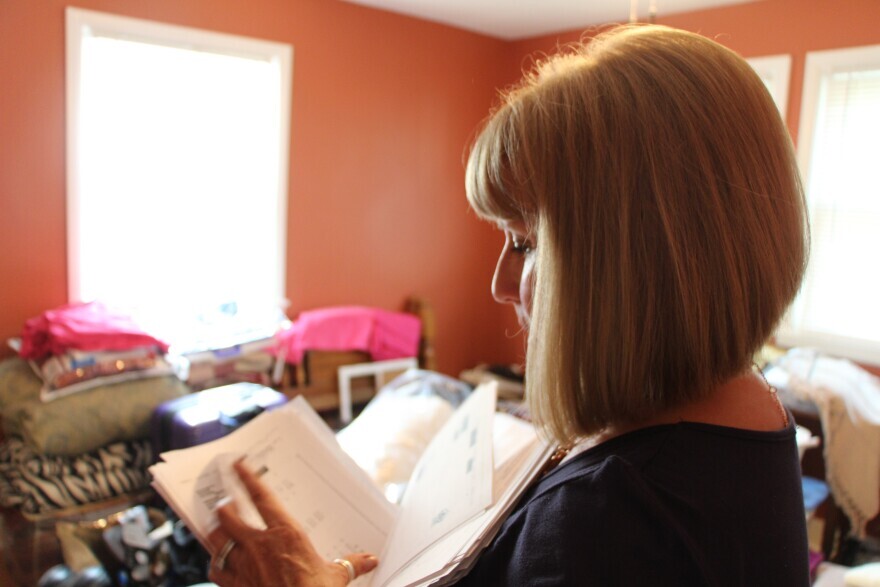

Michaela Shelton, the family’s attorney, said she was disappointed in the ruling and would seek to have the case transferred to the Missouri Supreme Court.

The case of Adrian Jones drew national attention because of the horrific abuse the child suffered as the family shuttled between homes in Kansas and Missouri. Both the Kansas Department for Children and Families and the Missouri Department of Social Services received numerous hotline calls reporting that the child and his siblings were being abused beginning when Adrian was around 2 years old.

Authorities found the child’s partial remains in November 2015 in a barn near their Kansas City, Kansas, home and concluded he had died of starvation. His body had been fed to pigs.

Adrian’s father, Michael Jones, pleaded guilty to first-degree murder in 2017 and was sentenced to life in prison with no possibility of parole for 25 years. His stepmother, Heather Jones, also pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison.

The child’s torture and abuse was captured by some of the dozens of surveillance cameras installed in the Jones' Kansas City, Kansas, rental home.

Jerome Gorman, then the Wyandotte County prosecutor, said the case was "one of the worst things" police investigators had ever seen.

After Adrian’s death, family members, including his biological mother, one of his sisters and his maternal grandmother, filed nearly identical lawsuits against social workers in both Kansas and Missouri. The lawsuits, which referred to the child by his initials, A.J., alleged that the social workers had a duty to protect him from the foreseeable danger of harm from his father and stepmother. The suits sought $25 million in punitive damages.

“Unlike many other abused and neglected children whose abuse occurs under a veil of darkness and secrecy, A.J.’s mistreatment was the repeated subject of a seemingly endless series of reports and hotline calls to social workers and social service agencies in both Kansas and Missouri,” the lawsuits stated.

Although the Missouri Department of Social Services determined that Adrian was the victim of neglect, it decided to provide intensive in-home services rather than remove him from his home. Both lawsuits say that Adrian was sent to various therapists and mental health institutions but was always returned to his father and stepmother.

The Kansas lawsuit remains pending in Wyandotte County District Court.

The Missouri lawsuit was thrown out last year by Jackson County Circuit Judge Charles H. McKenzie, who found that the defendants were protected by official immunity.

The purpose of the official immunity doctrine is to allow public officials to make judgments about public safety and welfare without having to worry they’ll be held personally liable.

On appeal, the family argued that the defendants were not entitled to official immunity because the doctrine only applies to discretionary acts — decisions made by social workers in the course of their official duties — and not ministerial or clerical acts they were required to undertake by statute. In this case, they said the defendants were required to refer Adrian’s case to the proper authorities and failed to do so.

In its decision upholding McKenzie’s ruling, a three-judge panel of the Missouri Court of Appeals in Kansas City found that the defendants’ acts were discretionary because they had to decide how and to whom to report the information they received about Adrian.

Referring to a 2019 Missouri Supreme Court case, the panel said the “employees’ decisions as to what actions to take following hotline calls of abuse, followed by their own investigations and necessarily weighing the interest and safety of the child against the goal of keeping the family intact are equally far from the sort of ministerial or clerical acts contemplated by the ‘narrow’ exception to official immunity.”

Presiding Judge Mark D. Pfeiffer filed a brief concurring opinion, saying he agreed with the court’s statement of the law. But he said he was writing separately “to express my sincere hope that nothing about this case feels like a ‘victory’ for anyone associated with it.”

Pfeiffer said he understood and respected the stress experienced by social services investigators. But he said the allegations did not present “a flattering portrayal for how the Social Services system worked to protect a little boy named A.J.”

“Our system let A.J. down,” Pfeiffer wrote. “Let us never forget A.J.’s story. Let us all learn from it. Let us all be resolved to never let it happen again. To A.J.—May your soul rest in peace.”