Friday night is a great time to look up at the sky, if you live on the north side of Missouri and Kansas: the northern lights, or aurora borealis, will make a rare Midwest appearance.

A geomagnetic storm caused by solar eruptions could make the lights — which are ordinarily seen from Alaska, the North Pole and other northern latitudes — visible farther south.

The best views will likely come around midnight, as the storm is expected to be at its strongest between 11 p.m. and 2 a.m.

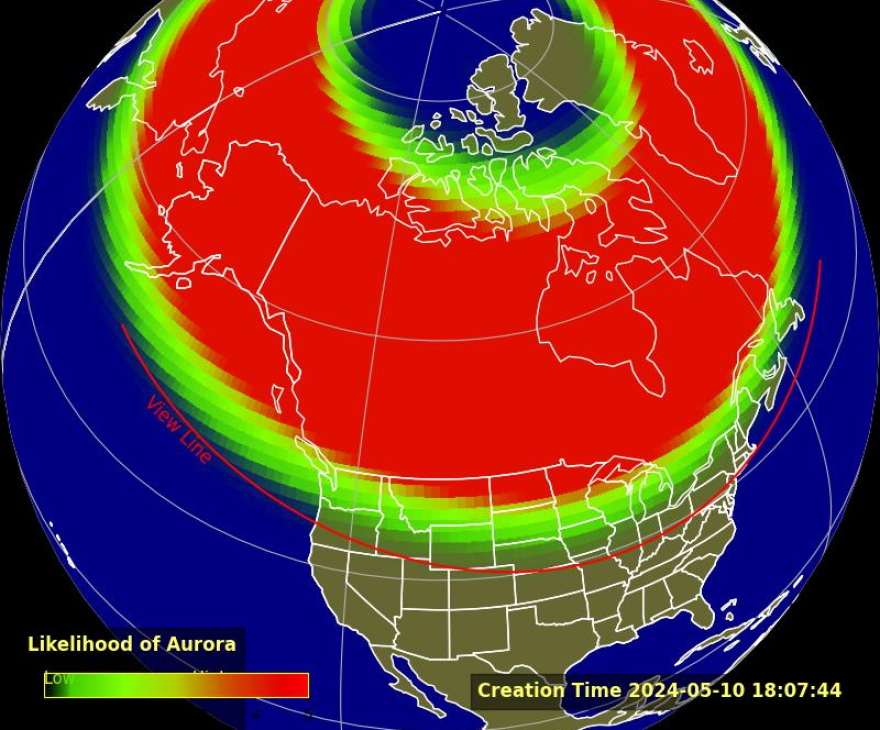

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says the aurora can be observed from as far as 1,000 kilometers away when it’s bright and if conditions are right — it doesn’t need to be directly overhead.

The predicted viewing line barely includes Kansas City and St. Louis, and sweeps up through the northwest corner of Kansas. The farther north you can go, the better your view will be.

National Weather Service meteorologist Nathan Griesemer told Kansas Public Radio that conditions are favorable to catch a good view.

“We should have mostly clear skies tonight,” he said. “If we look close to the horizon tonight, we might be able to see a little bit of a hue of the aurora borealis.”

NOAA reported that a “large sunspot cluster," 16 times the size of Earth's diameter, is producing strong solar flares this week, along with what are called coronal mass ejections (CMEs). Those events are “explosions of plasma and magnetic fields from the sun’s corona," NOAA says.

The resulting geomagnetic storm is ranked as G4, a "Severe" category. NPR reports this is the first G4 storm to hit Earth in nearly two decades.

G4 conditions have been observed... pic.twitter.com/uWZC96N9F1

— NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center (@NWSSWPC) May 10, 2024

The storms may disrupt communications and navigations equipment, cause power outages and even hurt satellites. But it's also what will give us the nighttime display.

“Stronger disturbances around the sun can pull Earth's magnetic field away from the planet, and when the magnetic field snaps back, it causes Alfvén waves, which electrons sometimes cling to,” NPR reports. “When those electrons reach Earth's atmosphere, they mingle with nitrogen and oxygen molecules, causing visible light that manifests as the aurora borealis.”

You can learn more about how the aurora borealis happens from NPR’s Short Wave podcast.