The soft glow of candlelight flickers and wraps around a makeshift altar at the base of Art Hill.

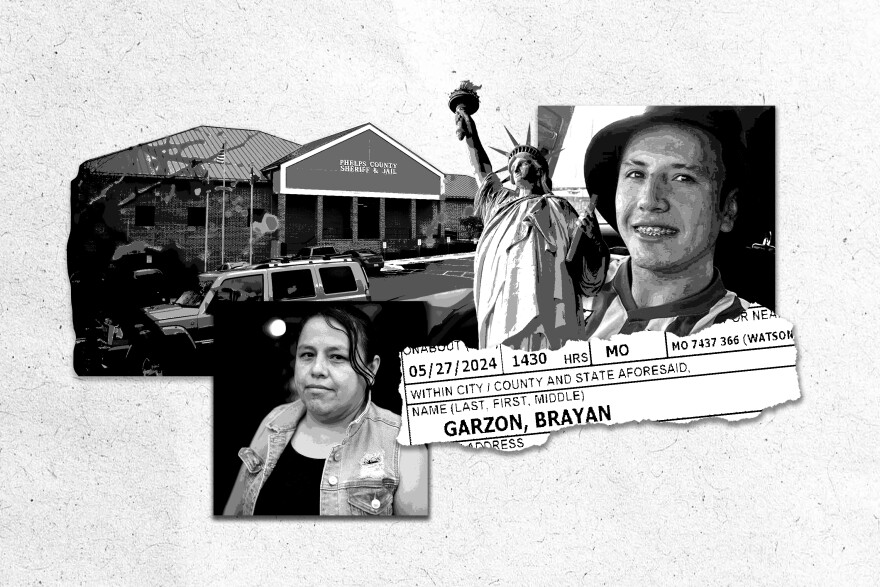

A portrait of Brayan Garzón-Rayo is taped at the altar's base, surrounded by white balloons bobbing gently in the breeze as his green-and-white soccer jersey — a nod to the Colombian soccer team Atlético Nacional — is neatly laid out in front of his image.

Lucy Garzón, his mother, stands quietly before the shrine as tears well in her eyes. Her eulogy is inscribed under her son's image: "En la tierra, mi guerrero. En el cielo, mi angel." On Earth, my warrior. In heaven, my angel.

The haunting ballad "En Otra Vida" plays over a speaker as Lucy Garzón and about a dozen family and friends weep before praying. The artist's lyrics echo across the largely empty park.

Y ahora que tú te vas

Me quedó atrapado aquí en esta prisión de oscuridad

Y desde ese día tengo mi corazón a la mitad

Pero en otra vida sé que tendremos la oportunidad.

Now that you leave

I am left trapped here in this prison of darkness.

Since that day, I have lost half my heart

But in another life, I know we'll have another opportunity.

Not two years after arriving in the country, Lucy Garzón is left grieving at this makeshift memorial after her son died while in the custody of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Now she is demanding answers about what happened and why his last days were marked by apparent illness, self-harm and despair.

Garzón-Rayo was 27. He loved zipping around on his motorcycle, watching soccer with friends and sledding down Art Hill during a fresh snowfall. Most of all, he was devoted to his family, his mother said, and fought tooth and nail to ensure they would have a better life here than in their native Colombia.

"Mom, you have to live life because you never know," Lucy Garzón recalled her son telling her. "One day you may be here, and the next you may not."

Journey to St. Louis

Lucy Garzón is a soft-spoken 45-year-old woman with long, dark hair. She speaks matter-of-factly about her life and struggles, including starting her life in a new country.

Her family's time in Bogotá became more and more challenging over a span of months. It ultimately reached a breaking point at the end of 2023 after they received growing threats of violence and harassment from law enforcement. She loved Bogotá, but the situation had become untenable.

"We know [in Colombia], there may be laws, and you may be able to sue, but nothing will happen," the single mom said, noting the country's struggles with femicide. "Filing a lawsuit is putting your life in jeopardy."

They left Colombia in early November 2023, and after weeks of hardship, Lucy Garzón and her four children reached the San Ysidro, California, port of entry — a stretch of the infamous wall of rusted metal spiraling toward the sky that stands at the center of the United States' geopolitical debate.

Lucy Garzón and her family tried and failed to get into the U.S. two times but got in on the third attempt during the wee hours of Nov. 30.

"We felt so much joy because not everyone has the same luck," she said. "We thought about everything we could accomplish here."

Lucy Garzón said that the family wasn't welcomed to the U.S. with open arms and that their time with federal immigration officials was mired in racism. Since then, the family's asylum cases have been working through the legal system. Garzón-Rayo had not been part of the asylum process, his mother said.

"We were being treated like livestock," she said of the interactions with the ICE agents at the border. "They threw my son's money on the ground and made him pick it up on his knees."

While Lucy Garzón and three of her children were quickly released into the U.S., border officials held Garzón-Rayo behind for months. By the time the family reunited and settled in St. Louis, their fear of immigration officials had left its mark, she said. Still, they clung to hope, determined to build a new life together.

What started as a chase for the American dream quickly turned into a nightmare.

Arrest and custody

Lucy Garzón's new start in St. Louis was going well as she worked odd jobs to make a little money to support her family. She had also begun trying to figure out how to get her young daughter and granddaughter into the local school system.

Then, in May 2024, Garzón-Rayo was charged with shoplifting in Shrewsbury. He missed a court hearing in January, and the court put out a warrant for his arrest by the end of that month, according to court documents.

The Shrewsbury prosecuting attorney's office did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

In March, the St. Louis circuit attorney's office charged Garzón-Rayo with a misdemeanor for credit card fraud. Weeks later, he'd be dead.

According to a probable cause statement, Garzón-Rayo used a credit card that didn't belong to him at The Nic, a vape shop on Delmar Boulevard. Grainy security footage obtained by St. Louis Public Radio shows Garzón-Rayo and two other men at the store on March 11.

The footage appears to be a cellphone video of a security camera, but the image is indistinct. A man in a blue shirt, identified as Garzón-Rayo by family members, looks to be swiping a credit card while a man in a black shirt stands with his hands in his pockets and a third man approaches and talks with the two.

The statement claims Garzón-Rayo admitted to officers that he was given the card by another person who said it had been stolen. A police spokesperson said the owner of another store accused Garzón-Rayo of trying to purchase a bracelet with a stolen card.

Court documents show the other person, the one in the black shirt, said Garzón-Rayo's family, was Cristian Acuña.

The St. Louis circuit attorney's office filed three counts of stealing against Acuña. According to a probable cause statement, the man is alleged to have stolen jewelry and credit and debit cards from a hotel room and was taken into custody with a stolen watch on his wrist.

"Surveillance footage shows the defendant and a co-defendant Garzon[-Rayo] in a store using Victim 3's credit card," it states. "Further, co-defendant Garzon[-Rayo] stated to police that the defendant gave him the credit cards."

The public defender representing Acuña did not reply to a request for comment for this story.

Roughly two weeks after the credit card incident, Garzón-Rayo and his sister Deisy Garzón noticed several police officers taking pictures of their vehicles outside their home. Garzón-Rayo went to find out what was going on. That's when police turned Garzón-Rayo around, handcuffed him and put him in the back of a police vehicle, the family said.

Video of the March arrest obtained by St. Louis Public Radio shows Lucy and Deisy Garzón repeatedly asking several St. Louis Metropolitan Police officers what was going on and why they were arresting Garzón-Rayo.

None of the officers responded to their pleas in Spanish. It's not clear if any of the officers were able to speak or understand the language. One eventually asked if the family members had Garzón-Rayo's identification documents by calling out "identificación … casa," and gesturing to their home.

Deisy Garzón said an officer eventually told them that investigators had tied Garzón-Rayo to several instances of credit card fraud and were looking for Acuña. She said her brother told her police were going to let him go on bond, but his name came up with federal immigration officials because he'd missed an immigration court hearing in California. ICE officials said there was a deportation order filed against Garzón-Rayo in June 2024.

According to a St. Louis police spokesperson, the department "does not enforce federal immigration laws, but it is the policy of our department to contact Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) anytime an individual without legal citizenship is arrested for a crime."

Garzón-Rayo did not appear to have a public defender or private attorney representing him in either municipal case, according to court documents. A spokesperson for St. Louis circuit courts said that public defenders and other options for legal representation are assigned at the first hearing. Garzón-Rayo's first appearance would have been April 23.

The city police department said that it used a "Spanish-speaking officer" during an interview with Garzón-Rayo, but there is no order for a translator in any of the available court documents.

The circuit attorney's office has yet to drop the charges against Garzón-Rayo. Circuit Attorney Gabe Gore said while he couldn't comment on this specific case, the office can't drop charges against people who've died until it receives a certified death certificate from the recorder of deeds' office.

"Once we obtain that, we file an abatement by death motion, which is essentially a dismissal saying this case is being dismissed because the defendant is now deceased," Gore said. "We attach that death certificate so that the court can satisfy themselves that in fact, the defendant is deceased and the matter is dismissed."

Gore said it's not uncommon that a case is dismissed because the charged individual has died.

"From our perspective, this is a fairly routine issue … when you have someone die," Gore said. "The fact that this particular defendant died in ICE custody is tragic, but from our perspective, it doesn't impact the process at all."

The final days

ICE arrested Garzón-Rayo on March 25 after he spent a day in police custody and transported him 100 miles to the Phelps County Jail. There, the man's daily calls with his mother became a lifeline, always ending in a blessing from his mother.

The Garzón family had never heard of Phelps County or its jail. The Phelps County Sheriff's Department, which runs the jail, did not respond to multiple requests to comment for this story.

The mother and son had their routine call on April 3. Lucy Garzón remembers her son complaining of stomach pains and the poor quality of the jail's food. He asked her to send money to his commissary account. Garzón-Rayo also said he'd received medical care for stomach issues.

"[Brayan] told me: 'Mother, it was weird. The doctor told the officer something, and he made a strange face, but they didn't tell me anything,'" she recalled. Garzón-Rayo asked her, "Can we find out if there was a problem?"

Lucy Garzón said she ended the call, telling her son she had to take a late shift and would be getting off work in the wee hours of the morning. Garzón-Rayo agreed he would call her then to receive her blessing once more.

The next day's call never came.

Desperate for answers and with little information available — especially in Spanish — Lucy Garzón began making frantic calls. She reached out to the girlfriend of another detainee, someone who had once helped her with legal paperwork. She pleaded: "Can you please talk to your boyfriend? What happened to my son?"

The detainee told Lucy Garzón that her son had become incredibly anxious and was taken out of his cell along with his belongings. He didn't know when Garzón-Rayo would return.

"I was left worried and started asking: 'Did he get sick? Is he hospitalized?' I imagined any other thing," she said. "It's so weird because no one has told me anything."

Lucy Garzón's phone finally rang on April 7, around 11:30 p.m.

At first, she felt relieved when she recognized the Phelps County Jail's phone number.

"He tried to take his own life, and he's in a Rolla hospital," Lucy Garzón remembers the jail worker told her. "He is going to be transported to a St. Louis hospital at 3 a.m. by helicopter because his situation is critical, and he may die tomorrow."

The rest of the call was a blur, she said.

A worker at the jail told Lucy Garzón her son had hanged himself with a bedsheet in his cell and was found unresponsive. The worker then told her that Garzón-Rayo was revived and transported to Phelps Health Hospital.

A source close to the investigation, who had viewed security camera footage of the incident but is unauthorized to speak about it, corroborated the account. The source told STLPR that Garzón-Rayo was alone when he attempted to take his life.

The Colombian man was transported overnight to Mercy Hospital South in St. Louis County. It was there that doctors determined Garzón-Rayo was brain dead, his mother said.

In a statement, federal immigration officials said they work to protect the medical well-being of their detainees.

"ICE remains committed to ensuring that all those in its custody reside in safe, secure and humane environments," the agency said. "Comprehensive medical care is provided from the moment individuals arrive and throughout the entirety of their stay."

Phelps County Coroner Ernie Coverdell ordered Garzón-Rayo's body transported to Crawford County for an autopsy, which a St. Louis-area medical examiner performed. Coverdell said the final report is expected in the coming weeks.

Lucy Garzón wants to have her son buried in Colombia but said she doesn't have the money to have his body repatriated. She's weighed having him cremated and sending his remains home, but she can't afford that either.

Garzón-Rayo's remains are being stored in a morgue in Cuba, Missouri. That's what weighs on Lucy Garzón most now, she said.

"Every day I wake up with that emptiness in the pit of my stomach, knowing I still haven't been able to give him a proper burial," she said. "That's what has me drowning right now."

More questions

Lucy and Deisy Garzón lamented that there have been more questions than answers surrounding Garzón-Rayo's death.

"The only people who have meaningfully reached out to us are the organ donation people and the hospital," Lucy Garzón said. "The only thing the police spoke with me about was to put me in touch with someone from ICE to pick up his things."

St. Louis police officers returned Garzón-Rayo's cellphone and attempted to interrogate his mother about the criminal accusations against her son and Acuña. The officers left after she declined to talk about the case and told them she was in mourning. A police spokesperson said that visit was when the department learned of Garzón-Rayo's death.

Missouri Highway Patrol Sgt. Brad Germann with the agency's Division of Drug and Crime Control confirmed the patrol opened an investigation into Garzón-Rayo's death. Yet, Lucy Garzón said she learned of the investigation from an STLPR reporter and never received communication from the Highway Patrol about it.

Following Garzón-Rayo's death, Lucy Garzón said other jail detainees began to reach out to her with condolences and to share concerns over the conditions at the Phelps County Jail. The mother recalls one detainee telling her they would have rather received the death penalty than spend time there.

Lucy Garzón fears the jail and its staff pushed her son to — and eventually over — the edge. But, she said, the signs may have been there.

Another detainee told her that her son had previously thrown himself down a flight of stairs in an attempt to injure himself. He was subsequently medicated and laughed about the situation, she said. The detainee told the mother that Garzón-Rayo would also violently throw up, and others would yell and smack the cells for help from guards that never came.

"Indirectly, they pushed him to do this," said Lucy Garzón. "He didn't have the drive to kill himself. He didn't have a reason to do so. He was a young and healthy man. Yes, he had difficulties like every family, but not to take his life."

Lucy Garzón said that her efforts to advocate for her son were ignored and that the system failed him. For every question answered about what happened in the period leading up to Garzón-Rayo's death, more remain.

The Colombian mother said she will keep fighting to learn what happened to her son and prevent it from happening to other families.

"That's what he would have wanted," she said. "I have to keep fighting for the truth."

This article is a collaboration between St. Louis Public Radio and The Midwest Newsroom.

The Midwest Newsroom is an investigative and enterprise journalism collaboration that includes St. Louis Public Radio, Iowa Public Radio, KCUR, Nebraska Public Media and NPR.

There are many ways you can contact us with story ideas and leads, and you can find that information here. The Midwest Newsroom is a partner of The Trust Project. We invite you to review our ethics and practices here.

Copyright 2025 St. Louis Public Radio