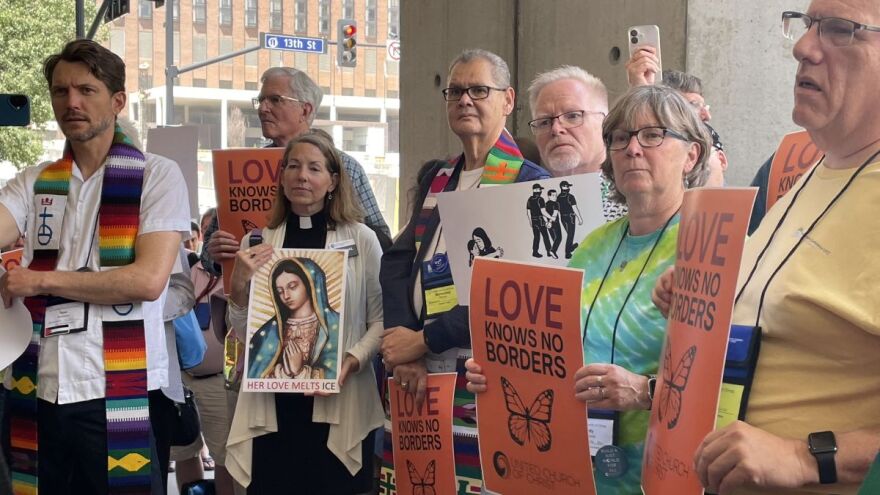

The clergy, 250 strong, gathered on the steps of the Kansas City Convention Center.

They proclaimed a clear, moral argument opposing the Trump administration’s mass deportation campaign targeting immigrants. “God knows no border” was among the chants.

They were among thousands attending the United Church of Christ General Synod in Kansas City July 11-15.

The group passed a resolution against the Trump administration’s tactics on immigration, in addition to holding the prayer session and rally outside Bartle Hall.

Their message about human dignity and fairness has echoed in recent weeks in nationwide protests — and in Kansas City.

“God will win this conversation,” the Rev. Randy Mayer of Arizona said.

Still, there was wide acknowledgment that the burgeoning business of deportation is an imposing opponent, gilded with financial incentives.

“We’re not naïve,” said the Rev. Sarah Griffith Lund, a native of Columbia, Missouri. “It’s about the money.”

Lund, now a senior minister in Indianapolis, is on the UCC’s national staff.

Lund, like others in the group, said she was painfully aware of the profit motives entwined with the government’s efforts on immigration.

But she said respect for the humanity of immigrants targeted for deportation and concern for families who will be separated must remain the focus of faith communities.

Mass deportation profit motive for CoreCivic

Elsewhere, another view pushes the argument for well-paying jobs, tax revenue and funding for communities willing to play a role in the administration’s goal of removing 3,000 undocumented immigrants daily.

Leavenworth is a prime local example.

There, the private prison company CoreCivic is in a legal battle with the city. The company is intent on opening an immigrant detention center capable of holding more than 1,000 people without obtaining a special use permit from the city.

In a July 11 filing, a Kansas district court judge upheld a temporary injunction prohibiting CoreCivic from housing detainees, while legal arguments are weighed in the courts.

CoreCivic signed a no-bid contract with the federal government that would pay it $4.2 million a month to house immigrants at the Leavenworth site, the Kansas Reflector reported.

CoreCivic owns the property, which operated as a federal prison until December 2021.

The Leavenworth Detention Center closed after the Biden administration phased out federal contracts with privately operated prisons. The decision was made in part to reduce the profit incentives of incarceration and to address concerns of safety and racial equity. CoreCivic’s prison in Leavenworth experienced staffing problems, alleged violations of detainees’ rights and safety issues, including attacks on guards.

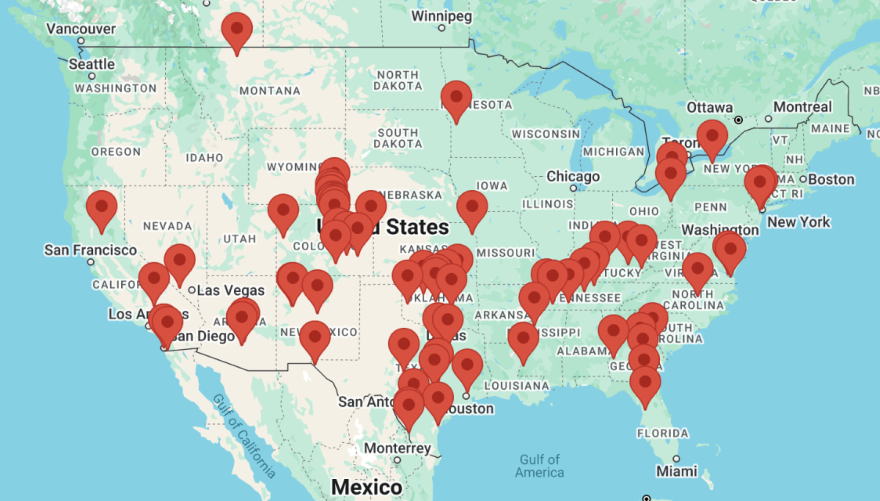

CoreCivic is a Tennessee-based, publicly traded company that operates prisons and detention centers across the country. It reported total revenue of $2 billion and net income of $68.9 million in 2024.

In recent months, CoreCivic has made charitable donations in Leavenworth, pumped a reported $500,000 into the local economy through contract labor at the former prison, and hired more than one-third of the workforce that it will need to operate the site as the Midwest Regional Reception Center.

“We want to reiterate our strong desire to work in close partnership with Leavenworth and its leaders,” said Ryan Gustin, senior director of public affairs for CoreCivic.

The $500,000 the company has spent locally since the beginning of the year includes contracts with lawn care crews, plumbers and electricians, Gustin said.

“Even when the bids we solicit come in slightly higher, we often choose the local option if we know the contractor understands our policies and security protocols,” he said.

Leavenworth officials argue that CoreCivic needs to obtain a special use permit to open its facility. City Manager Scott Peterson said the city’s concerns include the facility’s “past record of mismanagement and burden on core city services.”

CoreCivic maintains that it does not need a new permit.

Gustin said the company has worked “to both listen to and be transparent with the community.”

“We’re grateful for a more stable labor market now, and we’ve had a positive response from job seekers interested in the positions the facility will create,” Gustin said.

Congress just ensured federal funding for deportation contracts like the one CoreCivic signed.

President Donald Trump signed a measure dubbed the One Big Beautiful Bill on July 4.

The bill included more than $170 billion for immigration enforcement, with $45 billion earmarked for more detention centers like CoreCivic’s.

Congressional passage of the federal funding was closely watched by local groups, such as Advocates for Immigrant Rights and Reconciliation of Kansas City.

Karla Juarez, executive director of AIRR, also spoke at the recent rally outside the convention center in Kansas City

She stood among those wearing clerical stoles and collars, hoisting posters of Our Lady of Guadalupe, the patron saint of Mexico. The saint was pictured with the added message “Her Love Melts ICE,” a reference to Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

“We will not let our neighbors be disappeared in silence,” Juarez said. “We are sending a message to our community that you are not alone, we are here for you.”

The next day, Juarez led an evening session in southern Johnson County to build more support for immigrants, and to push back against the Trump administration’s policies.

The well-attended event was part of ongoing sessions by AIRR to train Kansas City area residents in immigrant rights and to draw allies to AIRR’s efforts.

Temporary injunction upheld

Kansas 1st District Court Judge John Bryant last week upheld the temporary injunction stopping CoreCivic from opening the Leavenworth site.

It’s the latest in a litany of legal arguments surrounding CoreCivic’s plan to open the former prison as a detention center.

CoreCivic maintains that it does not need a special use permit because it never shuttered or abandoned the site.

“We are pursuing all avenues to find a successful conclusion to this matter,” Gustin said. “We maintain the position that our facility, which we’ve operated for almost 30 years, does not require a special use permit to care for detainees in partnership with ICE.”

Bryant has noted that when the city revised development regulations in 2012, the then-federal prison was grandfathered in as “an existing special use and a lawful conforming use.”

But by the end of 2021, the Biden administration moved to close such privately owned federal prisons. The company’s contract with the U.S. Marshals Service expired.

The city administratively rescinded the grandfathered permit on March 25, 2025.

Bryant has also noted that the city “must have the ability to regulate itself by enforcing its own laws.” He concluded that upholding the temporary injunction also favors the public interest, because “allowing CoreCivic to begin to house detainees without a proper determination on its permit status undermines the confidence and trust of the public in the city’s ability to enforce its own regulations and ordinances.”

Bryant also has noted that in recent months, CoreCivic’s website listed the Leavenworth location’s status as “currently inactive.”

Mass deportation money for Leavenworth

In spite of the ongoing legal fight, CoreCivic keeps hiring in Leavenworth.

Gustin said the company as of July 1 had more than 2,000 unique applicants who have submitted more than 3,000 applications for jobs at the Leavenworth location.

The company also emphasizes financial benefits the company has offered to Leavenworth.

Those benefits include a one-time impact fee of $1 million, a $250,000 annual impact fee and an additional $150,000 annual impact fee to the police department. Those are in addition to more than $1 million in annual property taxes CoreCivic already pays.

The company made a $10,000 donation to the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 56 in Leavenworth earlier in 2025.

The Salvation Army of Leavenworth also received $10,000 from CoreCivic.

CoreCivic is betting that its financial impact may prove tempting to Leavenworth, which has a population of more than 37,000 and covers nearly 25 square miles.

The city is known as a location for prisons, but also for the heavy military presence of Fort Leavenworth, which includes the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College.

But Leavenworth has an unemployment rate that is higher than the statewide unemployment rate, according to the city’s last budget. The city also is concerned about an overreliance on sales taxes, which tend to be more volatile than property taxes.

Leavenworth is holding study sessions for its upcoming budget. Peterson, the city manager, noted in an email that revenues from local sales taxes have declined in recent years and that the current proposed budget does not include pay raises for city staff.

CoreCivic emphasizes those issues in its push for a detention center in Leavenworth.

“During a time when sales tax revenues are decreasing and pay raises for city workers are on hold, we feel strongly that an operational MRRC could help the city better navigate these budgetary constraints,” said Gustin in an email.

But CoreCivic isn’t the only option for addressing Leavenworth’s budget concerns.

Peterson said the city is pursuing savings by switching to the Kansas State Employee Health Plan. If successful, that will allow the city to reduce its mill levy and give pay raises for city staff.

New development is also being pursued, he said.

“The City Commission is actively working on solutions to refilling Leavenworth’s historic downtown, and finding economic growth in other parts of the city, to address this need,” Peterson said in an email.

“If CoreCivic is truly concerned about the Leavenworth community, and the role that CoreCivic can play in its growth, then I’m sure they would be happy to apply for a special use permit, which is all that the city has asked them to do from the beginning,” Peterson said.

This story was originally published by The Beacon, a fellow member of the KC Media Collective.