Kansas is the only state or local government to pass a plan to fund a Kansas City Chiefs or Royals stadium project.

Dysfunction in the Missouri General Assembly might also mean the Show Me State has nothing to offer. A last-minute plan by Gov. Mike Kehoe to help finance stadium projects for the Royals and Chiefs wasn’t even debated in the Senate.

Missouri lawmakers return June 2 for a special session to, among other things, pass a stadium proposal. But as it stands now, Kansas is in the driver’s seat to get, in theory, both the Royals and Chiefs. Notably, an affiliate of the Royals recently purchased a mortgage in Overland Park secured by the Aspiria campus, which is at 119th Street and Nall Avenue.

But economists say Kansas can’t afford both teams.

“You are not going to generate enough net revenue to cover one of the facilities, let alone two,” said Geoffrey Propheter, an associate professor of public finance at the University of Colorado Denver.

Propheter did say there’s a way Kansas could afford both stadiums, but that requires “cannibalizing activity from other businesses.”

A majority of Kansas lawmakers disagree, and say getting the Chiefs or Royals is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. But whether STAR bonds can support one or two teams depends on who you ask.

The Kansas STAR bonds proposal

STAR bonds, or sales and tax revenue bonds, are bonds that are paid by taxes generated in a bond district — hence the name. In a stadium proposal, taxes collected from bars, restaurants or any other businesses in the bond district would pay back the debt. Typically, STAR bonds are paid off in 20 years.

“(Kansans are) not going to pay a dime unless they visit the district,” Rep. Sean Tarwater, a Stilwell Republican, said last year.

That’s the logic behind the state’s proposal. Lawmakers last year approved a plan that would authorize Kansas to finance up to 70% of stadium costs with the bonds.

Supporters say the Chiefs and Royals would spark an economic boom that will bring new dollars into Kansas. All that economic activity would literally and figuratively pay off in the long run.

Almost 80% of STAR bonds projects are on track to be paid off early, the Kansas Department of Commerce said in 2024. STAR bonds have been used to finance other sports stadiums like the Kansas Speedway and Sporting Kansas City’s Children’s Mercy Park.

But STAR bonds have never been used for projects of this magnitude. A Chiefs or Royals stadium would be by far the largest project in the program’s history. And previous STAR bonds have only funded at most 50% of construction costs, not 70%.

The Kansas Speedway’s original bond was $24.3 million for a stadium that opened in 2001. That’s equivalent to about a $47 million bond when adjusted for inflation. Children’s Mercy Park received a $150 million bond before its 2011 opening.

Those figures would only cover a small fraction of the construction for a new Chiefs or Royals stadium. New stadiums for the Texas Rangers, Las Vegas Raiders and the Los Angeles Rams and Chargers opened in 2020. They had $1.2 billion, $1.9 billion and $5.5 billion price tags, respectively.

A 2021 audit from the Kansas Legislative Division of Post Audit found questionable returns from some STAR bonds. Notably, the Prairiefire project in Overland Park defaulted on its STAR bonds last year.

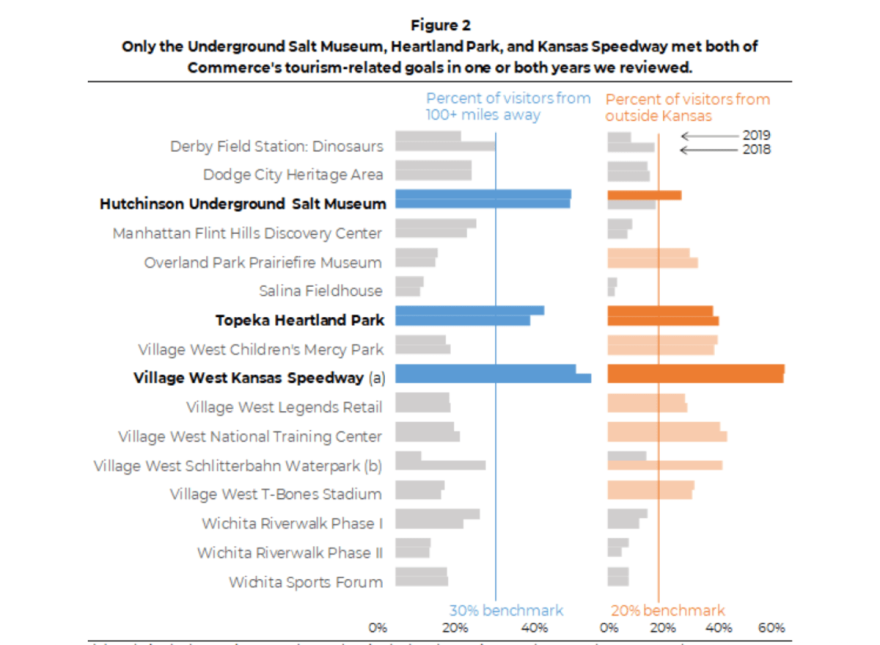

Topeka Heartland Park and the Schlitterbahn Waterpark in Kansas City, Kansas, also failed to pay back their bonds. And Strataca, the Hutchinson salt museum, is only projected to break even in 43 to 118 years.

Economists concerns

Propheter, the University of Colorado Denver associate professor, knows a lot about stadium funding plans. He said they don’t always work as advertised.

He said risk is unavoidable with these types of projects and they never start off profitably. It takes years to build the stadium and the surrounding district. That’s years of debt not being paid back.

Propheter said most of the money generated from the stadiums won’t be new to the metropolitan area. The Royals aren’t going to bring in tens of thousands of out-of-town fans for a Tuesday night game. But they will bring out tens of thousands of people who would already be spending money locally. These fans are spending money at the stadium instead of at a movie theater, bowling alley, restaurant or other local business.

Kansas wants projects financed by STAR bonds to attract 30% of their visitors from 100 miles away and 20% from outside Kansas. The 2021 audit of STAR bonds found that only three of 16 projects — the Hutchinson salt museum, Topeka Heartland Park and Kansas Speedway — met both goals.

A Chiefs or Royals stadium would likely draw a fair share of out-of-state visitors because the teams have been based in Missouri for so long. But Propheter isn’t convinced the economic activity will be worth it.

“A lot more people would travel to Kansas,” he said. “Would it be enough to generate the money needed to pay the debt? No.”

Nathaniel Birkhead, associate professor of political science at Kansas State University, also is wary of sales and other tax dollars being used to pay off bonds.

He said STAR bonds have struggled to pay off up to 50% of project costs before. Now, these bonds could pay up to 70% of one or more billion-dollar projects. That’s concerning to Birkhead.

“There’s some logic behind the STAR bonds,” he said. “However, I still fundamentally think it’s dishonest to say that something will pay for itself.”

Birkhead said the Chiefs, for example, are guaranteed no more than nine regular season games. The teams also could host concerts or other events to keep their stadiums busy, but there is no guarantee that happens.

He wonders how busy the STAR bond district will look when a game is not being played that day.

Then there’s uncertain economic projections. Ongoing concern about inflation and uncertainty around federal tariffs could make construction more expensive. A possible recession also would prevent people from spending money on sports events.

Building a stadium district

Brian Mayes, a lead political strategist who also worked on the Vote Yes! Keep the Rangers campaign in Texas, said there was a point in his life where he might have agreed that stadium debt is hard to pay off.

But Mayes, who has worked on the Dallas Cowboys and Texas Rangers stadium funding, said new stadium development is just different. There’s just so much economic development around these stadiums, he said.

Mayes said Rangers and Cowboys games always keep the businesses around the stadiums busy. But so too do the concerts, conventions and other stadium offerings. The Cowboys offer tours of the locker rooms, and people show up.

That’s not to mention mega events like hosting a Super Bowl.

Mayes remembers when the Cowboys left Irving, Texas, for the new stadium in Arlington. The old site of the Cowboys stadium still sits undeveloped. Meanwhile, Arlington now has a booming tourism district that is helping pay off other government projects.

“(We said) put the Cowboys to work for Arlington,” he said. “It was the economic generator, and the additional tax revenue that was made by the Cowboys helped the city pay for roads and parks and police.”

Scott Sayers is a senior technical architect with Gensler Kansas City. Gensler has worked on dozens of sports projects, including the Rams Village in Los Angeles, Capital One Arena in Washington, D.C., and M&T Bank Stadium in Baltimore.

Sayers said more people want to spend time before or after the game hanging around. Maybe they are talking about what they just saw or wanting to enhance the pregame experience.

Sayers doesn’t have specific opinions on STAR bonds and whether Kansas can afford one or two teams. But he does know that the Chiefs or Royals can create a prosperous stadium district if they work toward it — whether that would be in downtown Kansas City or suburban Kansas.

The state already did that when it created The Legends next to the Kansas Speedway and Children’s Mercy Park. Sayers said that area used to be an empty field before becoming a bustling, dense shopping and entertainment district.

The teams can build thriving entertainment districts when they treat the stadium and its surrounding areas as one cohesive community, he said.

“People have expectations,” Sayers said. “No longer are the days where 7:05, the event starts. I get dropped off at 6:40 … I want to start those experiences at 5 o’clock, at 4:30.”

This story was originally published by The Beacon, a fellow member of the KC Media Collective.