Gigi Dahl is one of the most popular kids at her new school in Ashland.

But at her old school in Omaha, she was often separated from her peers. Her parents — Jacob and Katy Dahl — said it was taking a toll on her.

“She would tell us she had sad faces,” Katy said. “She so desperately wanted to be part of the class.”

The Dahls have five children. Gigi, their youngest, has Down syndrome. At Omaha Public Schools (OPS), she started on a general education curriculum and moved to an alternative curriculum. She would have stayed with her peers for science and social studies, but the grading process would differ. For math and reading, she would be pulled out for lessons that matched her learning level.

Her education was meant to be based on the inclusion method, which includes students with disabilities in the classroom alongside their general education peers. In theory, the practice encourages equal educational opportunity for all students.

With no official enforced inclusion policy, the strategy’s success or failure largely depends on the district, the school, the teacher and the student.

In the past year, the Nebraska Department of Education (NDE) has promoted a “journey to inclusion,” as a better way to teach students with disabilities. It’s a newer practice for Nebraska schools, and administrators are confident it will work.

Amy Rhone, the state director and administrator of the Office of Special Education at NDE, said the model of integrating students with disabilities in general education classrooms is beneficial, as long as the classroom has the right support.

“Maybe a co-teaching model, and/or utilizing pullout for the most minimal amount of services and not interrupting core instruction, is actually more beneficial,” she said “It actually yields better results for students.”

Gigi’s school didn’t have the resources or space to accommodate her learning needs. She ended up staying in the back of the classroom to work independently on worksheets while her peers continued with other lessons. And for social skills, the school put Gigi into a kindergarten classroom, which the Dahls found inappropriate for a 10 year old.

“They could not grasp how to support her, ” Katy said.

An appropriate education

Students with disabilities are entitled to a Free Appropriate Public Education (FAPE). PTI Nebraska, the Parent and Training Information Center, helps parents learn how to advocate for their children with disabilities. Executive director Jennifer Smith-Miller said the word “appropriate” is key.

“Let’s say the kiddos are working on science, and they’re going to learn about all eight planets,” Smith-Miller explained. “If a kiddo might have alternate curriculum standards based on their needs, they’re still in that same classroom with their same-age peers, but they can have a different curriculum.”

The Dahls know from previous experience that it takes everyone’s support to make inclusion happen. They moved to Nebraska from Florida more than two years ago.

“We love Omaha. The support for the Down syndrome community here in Omaha is amazing,” Jacob said.

He is a member of DADS — Dads Appreciating Down Syndrome. His group meets regularly to support one another and their families as they navigate life with children who have extra chromosomes. Jacob said that unfortunately, support isn’t universal in the state’s largest city.

“There’s a genuine disconnect between the community support and the medical support, and the educational system,” he said. “It is a weird, very strange disconnect. It doesn’t make sense.”

The Dahls said district support is lost in Omaha right now.

“The schools, the principal, the resource teachers, the classroom teachers can all want to do it and all be on board with it and all go to the training,” Jacob said. “But without support from the district with extra paraprofessionals, with additional classroom resources for the teachers that are there, it will fail.”

Bridget Blevins, OPS administrator of external relations, said in an email the whole district is implementing inclusion, but the district is unable to comment on individual students’ experiences. She said the district works to meet individual students’ needs and provides “staff professional development through the year, review inclusion best practices and work to close gaps in areas that need attention.”

Research shows inclusion helps students with disabilities improve in literacy and math. Students in inclusion settings have higher attendance rates and are more likely to graduate from high school, to attend a post-secondary school and to be employed or live independently, according to a 2016 Harvard Graduate School of Education study.

That same Harvard Graduate School of Education study found students without disabilities can see improvement in their studies and are more accepting of others. Inclusion also helps teachers improve their ability to support individual student learning.

The realities of co-teaching

Samantha Jacobson has taught special education at Madison Senior High School in northeast Nebraska for more than four years and is in her eighth year of teaching.

She has an inside perspective of what makes a strong special education teacher, because she was a student with disabilities in David City. As a student, she was not separated from her general-education peers. And that’s something she adheres to as an educator.

“Being with my general peers, I didn’t want to be away from them,” Jacobson said. “I was very social. I liked being with my friends and so I think that helped me. It pushed me to want to be better and not just give up.”

At Madison, Jacobson employs inclusion. So far, she has found it benefits both her students and fellow educators.

She said inclusion is best implemented when special education teachers and staff have the capacity to co-teach in the classroom alongside general education teachers. However, that would require more special education teachers in a school building. That’s far from reality.

There were a little more than 24,000 public school teachers in the state for the 2023-24 school year, and 908 positions were left vacant or filled with someone who wasn’t fully qualified, according to the NDE.

Special education teachers made up most of those vacancies.

In the 2023-24 school year, there were 76 vacant special education positions. Another 133 positions were filled with someone who wasn’t a fully qualified special education teacher. Districts may have filled those positions with someone who doesn’t have an endorsement in special education, has a provisional or transitional teaching permit, or is a substitute teacher.

The Nebraska State Education Association President, Tim Royers, said in a statement the ideal teacher-student ratio “should be one teacher for every 6 to ten students, with paraprofessionals available to support students with complex needs.”

He said teacher’s union members are concerned budget cuts are increasing caseloads for special education teachers, leading to burnout.

The state education department will release data about teacher vacancies for the current school year this month.

The shortage of special education teachers means there aren’t enough to co-teach with general educators for an inclusion model.

“So how can we help those general education teachers be more prepared so they don’t feel like they’re being overrun?” Jacobson said. “Because the special education teacher is overrun and it is a ripple effect. And how can we support each other? I think it does start with that training process from the college.

“I think if we can teach [special education] in college, where future teachers are learning about special education as a core teacher, how can they supplement getting more than just that one quick crash course, it will help them be more prepared.”

Some educators said inclusion doesn’t solve burnout for special education teachers — one of the leading causes of shortages nationwide. According to a 2022 National Education Association survey of its members, 90% said burnout is a serious issue.

Data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows the number of children with disabilities in public schools has doubled in the past 45 years.

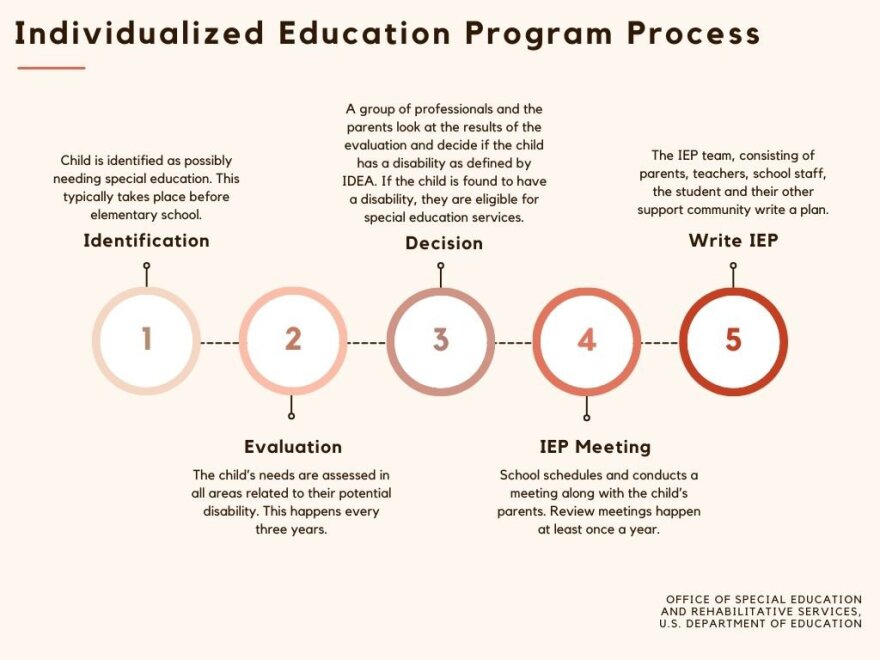

Students in special education have Individualized Education Programs (IEP). The process to determine details and create an IEP is defined by the U.S. Department of Education under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).

Other research shows special education teachers in inclusion-focused schools might have a larger workload because they are helping students not officially on an IEP. This led to more stress for educators.

Earning statewide buy-in

“Nebraska is so behind in [inclusion],” said parent Graciela Sharif. Her son was a student in Omaha. She frequently offers support to other parents throughout the state who have children with disabilities. “I mean, I still meet families who have an 18-19-year-old son or daughter with a disability who was never taught how to read or write.”

She explained this could be due to a lack of a rich curriculum, rather than no one trying to teach students with disabilities.

The NDE has noticed getting buy-in from each school district and each school within the district is a challenge.

Sharif is the chair of the state’s Special Education Advisory Council and mother to an adult son with Down syndrome.

But her experience was complicated by the fact that she immigrated to the U.S. from Peru and her husband is Palestinian. They came to a completely new school system without understanding how U.S. schools work, let alone special education.

Sharif tries to make sure immigrant voices are heard and valued in conversations regarding students with disabilities.

“I experienced with my son a lot of barriers: a lot of the systemic social barriers that exist in our educational system,” she said. “So I just felt that I needed to do something to just raise those concerns and to, together, find solutions.”

Sharif recalled when her son was starting kindergarten and how often her family faced discrimination, both because her son had a disability and because she felt the district could more easily take advantage of her having not grown up in the U.S. school system.

“We were not welcome. Doors were closed right in our face, telling us he doesn’t belong here,” she said.

So Sharif took it upon herself to learn about federal protections for children like her son and their right to an education. She now works with other parents with similar stories to explain their rights and feel empowered to advocate for their children.

PTI Nebraska encourages parents to collaborate with both special education and general education teachers in developing their children’s IEPs. But there are a lot of details that can at times be overwhelming for parents, according to executive director Smith-Miller.

“It is so important for parents to understand what their rights and responsibilities are for many reasons, so they can be very active partners in their child’s education,” she said. “Having the knowledge of their rights and responsibilities can help to ensure that [their] child is accessing a quality and meaningful education so their children can receive appropriate services.”

Eventually, Sharif said, after her advocacy the school learned how to support her son in what he needed as a student. But when they moved, they had to start all over again in a new school on its own path to inclusion.

“We were so thankful to that [prior] elementary school. They were just wonderful,” she said. “And then we moved farther west and that was a complete nightmare again. And then we realized that, OK, it’s not so much the district, it’s the school itself — who the leader is and what their mentality is when it comes to inclusion.”

Even though her son faced challenges in the general education classroom in addition to the initial discrimination, he gained valuable skills and knowledge from learning with his peers. He can read and write, he has a job and he knows Spanish.

These are all skills Sharif said are essential for people with disabilities to contribute to and

live in society; these are the same skills she said some students don’t learn if taken out of the general education classroom.

Pros and cons

Rebekah Hitz grew up in Nebraska and graduated from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln with a 7-12 special education degree in 2023. Shortly thereafter, she moved out of state.

She is now a second-year elementary teacher at Boston Public Schools.

“No matter how many tantrums they throw, how many times my room gets destroyed or how many times I get hit, they always come back,” Hitz said. “Teaching some of my students to multiply this year and seeing them be like, ‘Oh my gosh, look, I did it,’ and when I would say I was proud of them, their faces would just light up.”

In the Nebraska districts where she worked, Hitz said teachers do everything with the IEP. But in Boston, the special education coordinator plans and runs IEP meetings with parents while the educators can focus on teaching and tracking student goals.

“I only have to do the educational part, which is really, really nice,” Hitz said.

Not having to coordinate with all members of the IEP team helps the special education teachers take at least one thing off their plate to focus on what’s most important: teaching the students, Hitz said.

Gracyn Scott, a current University of Nebraska-Lincoln student, is studying special education and elementary education. She plans to stay in Nebraska after graduation.

She’s afraid of burnout, especially with how often the negative side of teaching is discussed on social media — stories of students misbehaving, teachers being attacked and parents being impatient.

“I just have to reassure myself that I do love this work,” Scott said. “I know I’m gonna absolutely love it even more once I have my own classroom and my own students.”

Scott sees the inclusion model as a positive development because she said it helps students and teachers.

“It’s showing that [the state] cares so much, not just about the education of students, but about their well-being,” Scott said. “I feel it can also help the teachers a lot because it helps them to know that their students are being cared for. When students are happier and have a more positive attitude within the school setting, that helps the teachers as well.”

The inclusion model needs support to work, though. Scott said elementary education majors at UNL take only a couple classes about special education, which isn’t enough to support a successful inclusion plan.

“A lot of elementary teachers are now going to have students with special needs in their classroom, and so just having one class from college isn’t necessarily going to prepare them for that,” she said.

Like school districts in Nebraska, Boston is focusing on implementing the inclusion model in schools. Hitz said in theory, it’s a great method.

“In an ideal world, it’s perfect, it’s amazing. It’s like how everything should be,” Hitz said. “But the problem that I’m seeing here, at least with how they’re trying to do it, is they’re like, ‘OK, we’re going to do full inclusion. You get one special education teacher for the full fourth-grade team,’ and you can’t do that.”

According to the National Center for Education Statistics, about 17% of students enrolled in Nebraska’s public schools during the 2022-23 school year were served under IDEA. The national average is about 15%.

Districts need to ensure the supports are there for inclusion to be successful, Hitz said.

“Are you putting the funding into the inclusion? Are you hiring enough staff for the inclusion? Are you allowing the time to plan?” Hitz said. “Those are the things that will make inclusion work or not work.”

Is funding the solution?

Nebraska has made funding changes for special education starting this academic year. Before this school year, the state would reimburse schools only 40% of their special education costs.

This made it difficult for smaller schools to support students with disabilities, according to State Sen. Rita Sanders. Sanders represents legislative district 45, which covers the city of Bellevue as well as Offutt Air Force Base. She is also the parent of an adult son with a disability.

She said the “word is out” for parents in the military with children who have disabilities. If they want the best option for their child’s education, they want to be stationed at Offutt.

“But it’s a financial burden on the schools to receive a higher amount of [students with disabilities] and be recognized for that when the reimbursements weren’t there,” she said.

Sanders introduced LB583, which increased the reimbursement rate to 80% starting this school year. The state senator estimates Nebraska has been a bit behind in developing best funding mechanisms for special education compared to surrounding states.

Sharif, who leads a support group for Spanish-speaking parents of children with disabilities, is looking forward to the possibility of funding for more qualified interpreters who know the ins and outs of special education.

“This is something that needs to come from the district to make sure that these interpreters know what they’re interpreting, so they can also act as liaisons and explain to the families what they’re signing,” she said.

Even as an English speaker, Jacob said special education terms and processes can be difficult to understand. Fortunately, Katy is finishing her degree in applied behavior analysis, so she helps with comprehension while Jacob focuses on taking notes during IEP meetings.

The Dahls’ decision to move to a smaller school district outside of Omaha, Ashland-Greenwood, has been a huge improvement for their daughter, allowing her to learn alongside her peers in a way that works best for her.

“She loves it,” Jacob said. “She’s totally independent there. They have all the supports that we could ever ask for.”

Inclusion has been helpful for more people than Gigi, Jacob said. It helps her classmates, too.

“It doesn’t really matter where we go, it’s ‘Oh, hey, there’s Gigi,’” Jacob said. “Her interacting with her age-level peers is very important; not just for her, though, it’s important for them. It’s showing them, it’s teaching them through experience that not everybody is a typical kid and not everybody learns at the same pace, but they’re still a normal kid of 11 years old.”

The Midwest Newsroom contributed to this story. We are an investigative and enterprise journalism collaboration that includes Iowa Public Radio, KCUR, Nebraska Public Media, St. Louis Public Radio and NPR.

There are many ways you can contact us with story ideas and leads, and you can find that information here.