For more stories like this one, subscribe to A People's History of Kansas City on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or Stitcher.

One of the first things you should know about Henry Perry is that he was equal parts pitmaster and entrepreneur.

To many, the reason for his success was simple: He knew how to smoke barbecue better than anybody.

"His food had an aroma that stayed with you. And that's what made them want to come back to him," historian Sonny Gibson says. "They traveled from as far as Leavenworth, Kansas, and Omaha, Nebraska. They would come down just to eat his food."

To others, it was Perry's marketing and business savvy that drew the crowds.

“Perry was the guy that stood up, wanting to make a living doing something that he liked doing," says Jim Watts, the ombudsman at the Black Archives of Mid-America. "So there probably were other people that barbecued that might've been a better barbecuer than Perry. But he was a businessman.”

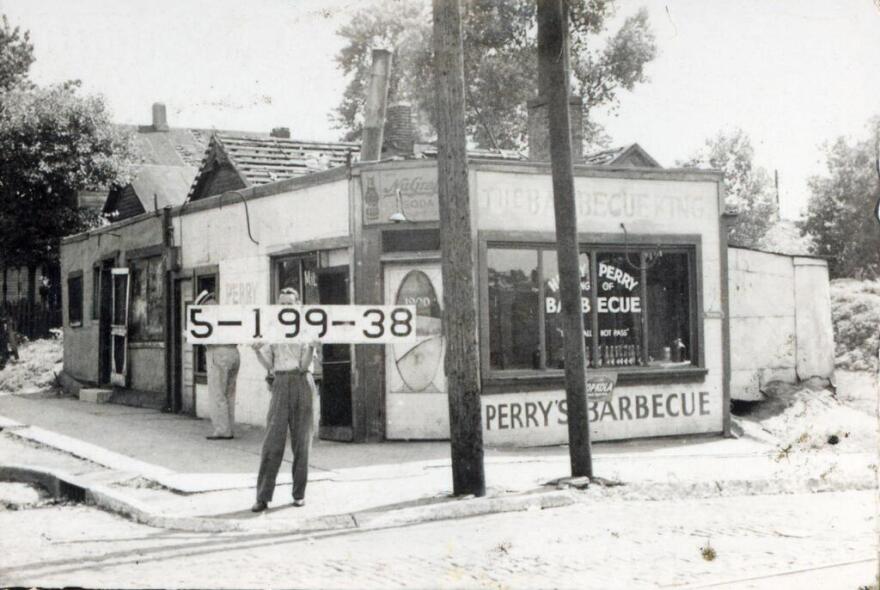

Perry's marketing prowess is reflected in the fact that we still refer to him as the barbecue king today, more than a century later. He didn't get the name posthumously, after all. He called himself the barbecue king. He was the one who put it in newspaper ads and plastered it on the window of his restaurant.

And even though he didn't create the act of barbecuing in Kansas City, Perry's arrival in 1907 from Memphis, Tennessee, did forever change the course of barbecue history here. Historians agree: Henry Perry coined the local style of Kansas City barbecue. He was also the first person in the city to open a barbecue restaurant and to truly make a living selling his meat.

Part of what was so alluring about Perry was his process. He picked up a lot of his barbecue skills working for restaurants on steamboats and to him, there was only one way to prepare barbecue: slow-cooked over a fire made from hickory and oak wood with the meat juices dripping directly on the coals.

But while Perry was picky about how he barbecued, he wasn’t picky about what he barbecued. “He barbecued and cooked everything," Gibson says. That meant possum, hog, raccoon and mutton, among other things.

Perry first sold meat from a stand in the downtown Garment District. There wasn’t any refrigeration, but it didn’t end up mattering, because he sold out every day.

Then he moved his operation to the 18th and Vine neighborhood where, in spite of it being the Jim Crow era, he consistently attracted a diverse customer base. During that time, Gibson says, you’d walk into a barbecue restaurant like Perry’s and see Black and white people eating together.

“It was a place where segregation ended when you walked through the door,” Gibson says. “People were just hospitable. They loved to sit there and eat barbecue.”

It’s not like barbecue was the great unifier. But, like jazz at the time, it was a place where Black and white people coexisted in ways they weren’t doing elsewhere.

“White people always liked our jazz and food, one being barbecue,” says Watts, from the Black Archives. “I think maybe there were some friendships and relationships that came from a white person being at the restaurant and a Black person just happened to be there… because people found out they had something in common.”

By the 1930s, people started following Perry’s lead. There were close to 100 barbecue restaurants in the 18th and Vine neighborhood.

Perry died of pneumonia in 1940, at age 66. But his influence didn't end there. He had taught three apprentices everything he knew and they carried on his legacy in two big ways. Arthur Pinkard became the first cook for the Gates family of Gates Bar-B-Q fame. And brothers Charlie and Arthur Bryant went on to create Arthur Bryant’s.

But in spite of all he accomplished, very few Kansas Citians know the story of Henry Perry today — including his own descendants.

Bernetta McKindra never met her grandfather, Henry Perry. She didn’t grow up hearing stories about him from her mother or her grandmother, either.

“He just wasn’t talked about. It was just known that he was the barbecue king,” McKindra says.

Then a few years ago, McKindra happened to overhear someone talking about how Henry Perry had been inducted into the American Royal Barbecue Hall of Fame. It spurred her to start researching the grandfather she never knew.

"It was not until I started to read and got older and saw other publications that I began to know that, 'oh, I think he really is someone,'" McKindra says.

Many Kansas Citians probably heard about Henry Perry for the first time on July 3, 2020, when Perry was honored with a “Henry Perry Day” in Kansas City and Jackson County, exactly a century after he fed 1,000 Kansas Citians for free on the lawn next to his restaurant. As an homage, Kansas City area barbecue establishments donated their supplies and time to prepare 1,000 free meals and then gave them away to local charities.

McKindra says that’s when it really sunk in for her that Henry Perry was someone special.

“It was a glorious time. It was a time of reckoning that not only was this man being recognized, but he also was my blood relative,” McKindra says. “The thing that has been most interesting to me is his tenacity… What was the drive that kept him going?”

Today, there is no longer a Perry’s Barbecue in downtown Kansas City. But there’s Gates. And Arthur Bryant's. Elsewhere, there’s Joe’s, Jones, LC’s, Jack Stack, Q39 and countless others. Some of these restaurants truly wouldn’t be around today if it wasn’t for Henry Perry.

And while they might not cook the meat directly on the coals in the style of the self-proclaimed king of barbecue, they’re still carrying on the tradition of barbecue excellence in Kansas City that Perry started in the early 1900s. These days, there’s just less possum on the menu.