Two recent cases involving prosecutors with the U.S. Attorney’s office in Kansas City, Kansas, point to a problem that some criminal defense lawyers say has been building for a long time:

For years, they say, a small group of federal prosecutors in KCK has run roughshod over the rights of criminal defendants.

A joint investigation by KCUR and KCPT reveals an underlying pattern of bullying and intimidation that at times has valued obtaining convictions over achieving just outcomes.

The two cases — one in which federal prosecutors gained access to taped attorney-client meetings at a Leavenworth prison and another in which a man spent 23 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit — and court documents offer a window into that culture.

Cheryl Pilate, a criminal defense attorney who represented the recently exonerated defendant, Lamonte McIntyre, blames a clique of attorneys whom supervisors have failed to rein in.

“There’s very little trust between the defense bar and some of the attorneys in that office – not all of them, but some of them,” Pilate said. “The office has been problematic for many years. It’s a combination of very strong, contentious personalities some of whom don’t appreciate the defense function.”

More than a dozen defense lawyers interviewed for this story agreed with that assessment. One even described it as a ‘Lord of the Flies’ situation. The lawyers declined to go on the record, however, because they regularly deal with the office and fear retribution.

Through its spokesman, the U.S. Attorney office — including acting U.S. Attorney for Kansas Tom Beall — declined to comment.

But a former manager in the KCK office, Mike Warner, described an “entrenched, bully prosecutor culture with years of weak, intimidated leadership.”

That leadership is about to change. In September, President Trump picked Kansas Solicitor General Stephen McAllister to serve as the next U.S. Attorney for Kansas. If the Senate confirms McAllister, a University of Kansas law professor and former dean of the law school, observers say he will have his hands full.

Ethical violations?

Prosecutors wield immense power, with discretion to determine whether and how to charge defendants, recommend pretrial detention and sentences, and negotiate plea bargains.

RELATED:The U.S. Attorney's Office In Kansas Has A Rich History

That power was on full display in the case of Lamonte McIntyre, who was prosecuted not by the U.S Attorney’s office but by the Wyandotte County District Attorney’s office. The prosecutor who tried him 23 years ago, Terra Morehead, joined the U.S. Attorney’s office 15 years ago.

From the outset, there were questions about McIntyre’s guilt. Arrested at the age of 17 for the 1994 shotgun killing of two men sitting in a car in Kansas City, Kansas, McIntyre was tried and convicted though no forensic evidence tied him to the crime and family members swore he was at home when the crime occurred.

The case against McIntyre, who always insisted on his innocence, was largely based on two witnesses’ testimony: one who said the killer vaguely resembled someone she knew with the name Lamonte; and an eyewitness who later recanted her testimony after saying she was coerced into fingering McIntyre by the lead detective in the case, Roger Golubski.

In their motion arguing that McIntyre was innocent of the crime, his attorneys accused Morehead, the prosecutor, of flagrant misconduct in the case, including:

- Failing to disclose that she had a romantic relationship with the judge just a few years earlier.

- Threatening to bring contempt charges against the eyewitness and to have her children taken away if she refused to testify against McIntyre.

- Withholding from the court that she had threatened the eyewitness.

- Suppressing witness statements that McIntyre did not commit the crime.

In testimony submitted at the October hearing that led to McIntyre’s exoneration, Lawrence J. Fox, a legal ethics expert and visiting lecturer at Yale Law School, said that both the judge and Morehead had committed multiple ethical violations, rendering McIntyre’s trial “fundamentally unjust.”

There can be no question, in my opinion, that Mr. McIntyre was critically disadvantaged by ADA Morehead's reprehensible conduct. - Testimony from legal ethics expert Lawrence J. Fox

“Not only was the entire trial marked by tacit partiality, it was also rendered overtly unjust by ADA (Assistant District Attorney) Morehead’s blatant acts of prosecutorial misconduct,” Fox said in a sworn affidavit. “In flagrant violation of her ethical duties as a prosecutor, ADA Morehead coerced a key eyewitness into perjuring herself on the stand and hid an abundance of materially exculpatory evidence from the defense. There can be no question, in my opinion, that Mr. McIntyre was critically disadvantaged by ADA Morehead’s reprehensible conduct.”

Defense attorneys say, and court records show, that Morehead has shown a similar pattern of maximalist positions since joining the Kansas City, Kansas, outpost of the U.S. Attorney’s office in 2002.

The Associated Press cited a 2012 federal drug conspiracy case in which she warned a defendant that if he sought release pending trial, she would file a motion subjecting him to a minimum 20-year sentence upon conviction.

In another especially noteworthy case five years ago, 42 defendants were charged with conspiring to distribute marijuana and cocaine. One of the defendants, Trent Percival, was given a mandatory minimum prison sentence of 10 years and ordered to forfeit $17 million — the same as the other defendants — even though he pled guilty and cooperated with the prosecution.

Morehead told the court that Percival had been untruthful and his assistance insubstantial, according to court documents — even though his information was used to obtain guilty pleas from other defendants.

U.S. District Judge Kathryn Vratil later granted Percival’s motion to vacate his sentence, and Morehead eventually agreed to a sentencing recommendation of five years and a forfeiture amount of $300,000.

In accepting the new sentencing terms, Percival agreed to forgo his claims of prosecutorial misconduct against Morehead.

In another multi-defendant drug case last year, a prominent defense attorney, Carl Cornwell, secured an acquittal for his client. As Cornwell was gathering his papers and preparing to leave, Morehead, who was the prosecutor in the case, demanded of him, “How does it feel letting a guilty guy go?” according to other attorneys who were present in the courtroom.

“It’s so unprofessional,” one of those attorneys said about Morehead and the KCK office in general. “The people in that office literally view the defense attorneys as being no different than the clients they represent. There’s no sense of proportionality.”

The U.S. Attorney’s spokesman, Jim Cross, declined requests by KCUR and KCPT to arrange for Morehead to comment.

Similar concerns have been raised about how the KCK office in general deals with drug conspiracy cases.

The Associated Press reported that before 2013 (when reforms were enacted), the office routinely filed motions in drug conspiracy cases that triggered mandatory decades-long prison terms – or even life sentences – for relatively minor drug offenses committed by suspects with prior convictions.

Power plays?

Longtime observers of the KCK outpost of the U.S. Attorney’s office say they could see the imbroglio over attorney-client tapings at Leavenworth coming a mile away.

The revelations surfaced after prosecutors in the KCK office tried to force an attorney representing a defendant in a related case to recuse herself.

The prosecutors accused the attorney, a respected criminal defense lawyer named Jacqueline Rokusek, of passing along to her client inside information that was given to prosecutors by a cooperating witness. They told her they had seen a videotape, recorded inside the prison, of her client with a document that may have contained the sensitive information.

After Rokusek asked to see the tape, she discovered that the private operator of the prison, CoreCivic (then known as Corrections Corporation of America), had made recordings of meetings and phone calls between attorneys and their clients — even though such meetings and phone calls were supposed to be protected by attorney-client privilege and off limits.

Some of those tapes were turned over to federal prosecutors as part of the drug smuggling investigation. Although federal prosecutors say they never deliberately sought the recordings but rather obtained them inadvertently as part of the discovery process, it has since emerged that at least one prosecutor in the KCK office listened to two of them.

That prosecutor, Erin Tomasic, is no longer employed by the office. But the apparent violation of what is considered to be a core element of the Sixth Amendment — the attorney-client privilege — has raised further questions about how the KCK office wields its immense prosecutorial powers.

“I think it fits how some of the prosecutors there view themselves and their power,” said Pilate, the veteran defense attorney who represented McIntyre. “It’s this sense that the badge that they have endows them with all kinds of powers, that they are not accountable to anyone except themselves.”

Another longtime criminal defense attorney called it “the most malicious, mean-spirited” group of prosecutors “that I’ve worked with my entire life.”

“They have been so awful in ways that I’ve never experienced in nearly 20 years of practice that I don’t want my name associated with anything that gets published anywhere,” he said, explaining his insistence on anonymity.

U.S. District Judge Julie Robinson, who is overseeing the prison contraband case and was once a prosecutor in the KCK office herself, appointed a special master to look into the audio and videotapings at Leavenworth and determine whether prosecutors sought to take advantage of them.

The appointment triggered a far-reaching investigation into the conduct of prosecutors in the KCK office and whether they knowingly accessed privileged attorney-client conversations.

The office has strongly denied that it had any hand in the tapings or that it was its intent to use them in the drug contraband case.

There has been a long-simmering culture of distrust occasioned by the prosecutorial practices of several prosecutors in the Kansas City, Kansas, division of the U.S. Attorney's office. - David Cohen, special master

But David R. Cohen, the special master, noted in one of his reports to the court that the case was “a spark that lit a flame of contentiousness” between the U.S. Attorney’s office and local defense attorneys.

“There has been a long-simmering culture of distrust occasioned by the prosecutorial practices of several prosecutors in the Kansas City, Kansas, division of the USAO (U.S. Attorney’s office),” he wrote.

One result, he said, has been a “diminished quality of justice for the entire community.”

In his last report to the court just a few weeks ago, Cohen, a Cleveland attorney who has served as special master in about 20 different cases for 15 different federal judges, dropped a mini-bombshell: The U.S. Attorney, he said, had stopped cooperating with him and would no longer supply him with information he was requesting.

That decision, he wrote, “is a drawing of shades against sunlight; this will not ameliorate any mistrust from the defense bar.”

Cover-up?

Judge Robinson herself has decried the conduct of some of the prosecutors in the KCK office. Their actions, she wrote in one of her orders, “demonstrated a troubling lack of transparency about the government’s knowledge, procurement, and use of the video recordings.”

She reserved some of her harshest criticism for Tomasic, the junior federal prosecutor who initially denied listening to any of the tapes and later acknowledged that she had. Tomasic could not be reached for comment.

Robinson also noted that a hard drive that had been in prosecutors’ possession and contained videos from Leavenworth had been wiped clean. Robinson had previously ordered all the hard drives that CoreCivic turned over as part of the special master’s probe to be preserved.

Few criminal defense lawyers believe that Tomasic acted on her own. In fact, criminal defense attorneys interviewed for this story say the problems in the office go far deeper.

Said one defense lawyer, who has practiced for more than four decades: “When you’re dealing with them, it’s like a different set of rules for some reason… I think they’re operating in a manner that it’s all ‘us against them’ and whatever we do to ‘them’ is OK as long as we get them.”

Us against them?

There is, however, no hard data to support that contention. The Justice Department does not break out figures on rates of prosecution and conviction for the individual offices – Kansas City, Topeka and Wichita – that make up the U.S. Attorney’s office for Kansas.

And defense attorneys emphasize that they have very little problem with the offices in Topeka and Wichita. Rather, their complaints are centered on the Kansas City, Kansas, office.

One member of the law enforcement community defended the KCK office and described the criticism as sexist.

“I just worked out a (plea) deal with the Topeka office, and they’re night and day,” said one defense attorney. “They’re not giving anything away – they’re federal prosecutors – but they’re polite, they’re kind, they answer phone calls, they respond to emails.”

One member of the law enforcement community who insisted on anonymity defended the KCK office and described the criticism as sexist, noting that the prosecutors being criticized are all women.

“It seems that the people in the KCK office who are the most criticized are a group of strong women that aren't afraid to take a case to trial rather than hand out an easy plea agreement,” he said.

But veteran defense attorney Carl Cornwell disputes that. While Cornwell was otherwise unwilling to be quoted on the record, he said he’s willing to be quoted on one matter:

“Barry Grissom never should have been a U.S. Attorney,” Cornwell said. “He did not run a tight ship. And that’s all I’m going to say about that.”

Weak leadership?

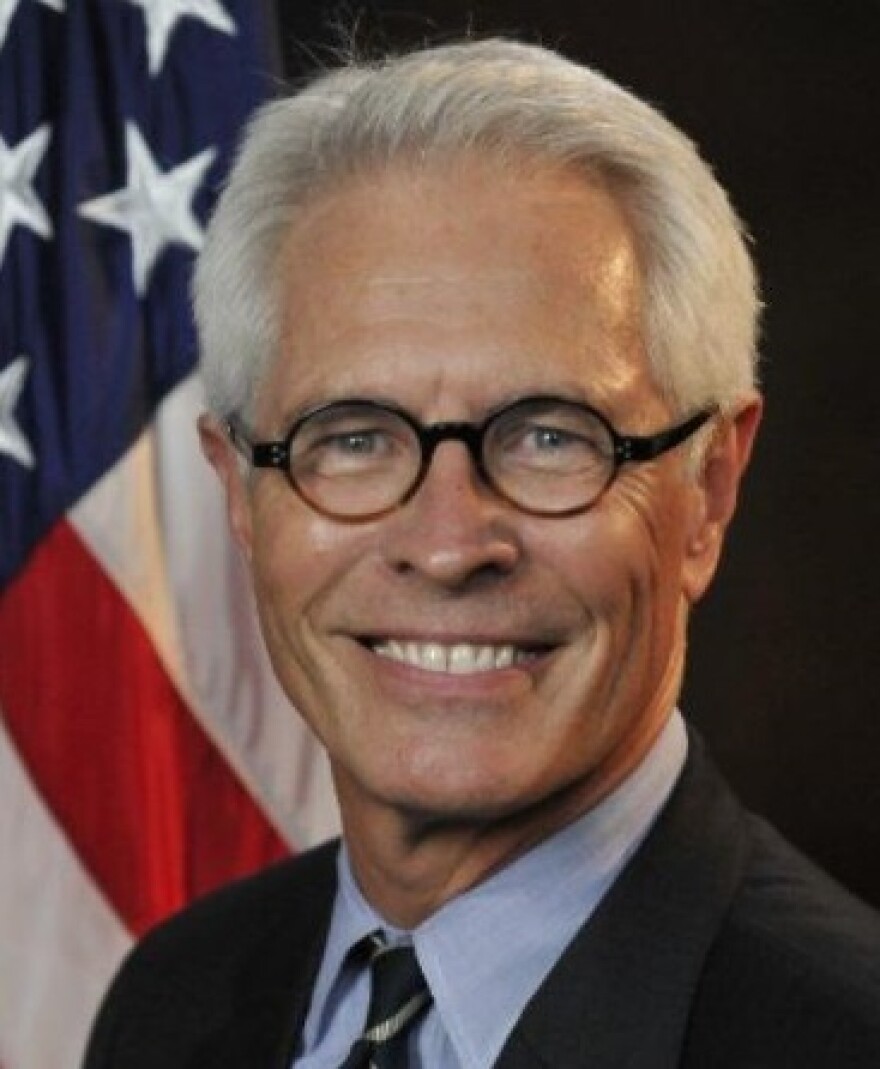

Grissom was a sole practitioner in Johnson County with little criminal law background or management experience when he was appointed by the Obama administration to lead the U.S. Attorney’s office for Kansas in 2010. He left in 2016 to join the Polsinelli law firm in Kansas City.

Mike Warner, who served in various management roles under Grissom, described him in 2012 as a “genuine” U.S. Attorney with no political ambitions – a man who had made the office “an instrument of public policy.” But Warner resigned in 2014, and he told KCUR and KCPT that he departed over Grissom’s management style.

If Grissom ever decides to run for political office, Warner said, “maybe he can explain why he didn’t confront and charge prosecutor misconduct during his watch.”

He added, referring to the tapings case in Leavenworth: “Right now, and for the foreseeable future, the Black case investigation is costing taxpayers a lot of money. They have a right to know how it happened and why someone in charge failed to act.”

A longtime federal prosecutor in the office, who has since retired, said he thought Grissom was “easy to manipulate, and that’s not a good thing.”

Other attorneys said Grissom tried as best he could to rein in prosecutors in the KCK office but, like his predecessors, was largely unsuccessful.

Grissom, asked about the criticism, said that attorney-client rules prevented him from commenting on cases that were brought during his tenure, including the taping investigation and whether he believes defendants’ civil rights were violated.

But when he was the U.S. Attorney, Grissom was fond of quoting a line from former top Department of Justice officials about how prosecutors should always be vigilant about protecting the rights of the accused:

"We're not the Department of Prosecutions,” he liked to say, “we’re the Department of Justice.”

Dan Margolies is a senior reporter and editor at KCUR 89.3. You can reach him on Twitter @DanMargolies.

Mike McGraw is the special projects reporter for KCPT's Flatland. Reach him at mmcgraw@kcpt.org.