The Latino community in Belton, Missouri, once a military and farming community, is growing.

Today, almost 10 percent of Belton’s 24,000 residents are Latino, with that number rising to about 18 percent in the Belton School District. And they have mixed reports about how included they feel in the community. Some believe non-Latinos are uncomfortable with demographic changes.

The growing Latino community has led to conversations about diversity and acceptance in the increasingly suburban city about 30 miles south of Kansas City. Some of those conversations are occuring in churches. Some in public schools. Some in the privacy of a family's home.

It's not a new community. Mexicans came to the Kansas City area to work on the railroads in the early 19th century, including two that went through Belton. There were Latino military with the Richards Gebaur Air Force Base after World War II who liked Belton and made it home.

A welcoming place for many

Yeni and Jesus Gonzalez have four children ranging in age from 8 to 18, all in Belton schools. Both of their mothers live with the family, as well. They rarely eat a meal together because of all the activities, appointments and commitments at church.

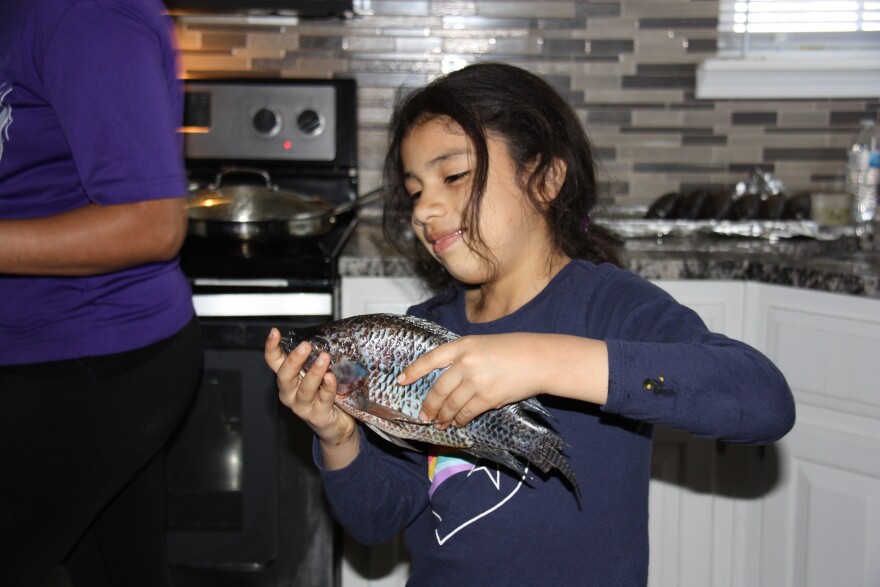

The kids love mojarra, the fish Yeni deep fries when she can get it. She says this particular species of fish is not available for sale in Belton so she travels into Kansas City to pick it up.

The family has moved a lot, and when they do, they try to live near other Latinos, but it was hard when they came to Belton.

“At first when we got here, we didn’t see too many (Mexican) faces. (But) I have not had any problems,” Yeni Gonzalez says. “I go to the store and nobody looks at me different. Everyone has been nice to me."

They enjoy the peace and quiet of a smaller town and found a spacious house with a big backyard that was more affordable than in the city.

Jesus Gonzalez loves Belton. But he also realizes his experience here may be different than that of newer Latino immigrants. As an active-duty Marine, he's well-traveled, fought in Iraq and knows how to deal with authority. But he can relate to the stories of more recent Latino arrivals.

“I was an undocumented Mexican brought here when I was 3 years old,” he said. “I got a green card, what they call an alien card, when I was 8 or 9. I got my citizenship at 25. So I can go back and say, am I a problem?”

Not everyone can call Belton home (yet)

Alicia and Miguel, who didn't want to be identified by their real names because of stuggles in the community, have lived in Belton for over 20 years. They say things like racial profiling and hostility toward Latinos has improved in recent years, but they still don't feel at home here. They have green cards and good jobs.

“We can’t say (Belton) is welcoming,” Miguel says. “Some people accept us and some people don’t, so we’re confused.”

When they first came to Belton, they lived in the neighborhood some refer to as “Little Mexico,” a neighborhood marked by run-down apartments and duplexes. Now they live in a quiet subdivision of split levels and small lawns.

They say they're among the few Latinos in their neighborhood. They had one friend, a policeman who was very helpful to them, but he’s moved away. In the 18 years they’ve been here, Alicia says no one has stopped to say hello or visit.

“We still have trouble to find nice people around us,” she says. “They don’t accept us and it’s hard.”

The schools

Teresa Balboa, bilingual coordinator for Belton schools, says this is an older community where the non-Latinos tend to be conservative.

“People just have the idea that if they see a Latino, you know, and especially if that Latino doesn’t speak English, that the person is here illegally,” she says. As a result, she says, very few Latino parents will come in to talk about their students if they’re having trouble. When they do, she says it’s frustrating that teachers and officials can be less than helpful to Spanish-speaking parents.

Patricia Benavides shares an office with Balboa and runs the Guadalaupe Center, a social service agency. She helps community members get public assistance, takes them to appointments and helps pay utility bills with emergency funds.

There was a time over the last few years, she says, that the office got calls that officers were waiting near St. Sabina Parish Church, a Catholic church where many Latinos attend, or on street corners, seemingly to pick up undocumented immigrants. But advocates talked with police, she says, and now things seem better.

“We used to have a lot of phone calls from wives, husbands and kids saying parents were arrested and taken to immigration,” she says. “Lately, I haven’t heard any of those issues.”

Belton Police Chief James Person, a lifelong resident of the community, acknowledges that Belton may be experiencing what he calls "growing pains," but he denies his officers were ever waiting to pick up undocumented immigrants.

“We do not hang out in the parking lots and we are not intentionally looking for minority drivers of any kind,” he said.

But he says he’s bound by state and federal law.

"If a Latina driving without a valid driver’s license is stopped for a tail light violation, they will be arrested for driving without a license, sent through the verification process, (and) if they don’t have any documentation, we will notify (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) before they are released," he says. “Then it’s up to ICE whether they have a detainer put on them or not.”

Immigrant advocates call that racial profiling, and say that police are not required by law to notify ICE.

Church community is a gathering place

The Gonzalez family, like most Latinos in Belton, finds a sense of community at St. Sabina Parish Church.

In March, they joined big crowd who came to hear a Salvadoran priest celebrate mass in memory of the assassination of Saint Oscar Romero, the human rights icon of the brutal Salvadoran civil war.

The message of Oscar Romero, who gave his life in the name of human rights and dignity for all, may resonate in Belton as the one-time rural town works to accept the diversity that is coming with growth.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly reported the percentage of students in Belton School District who speak English as a second language. That number is almost 6 percent, while almost 18 percent of students in the district identify as Latino. That information has been corrected.

Laura Ziegler is a community engagement reporter at KCUR 89.3. You can reach her on twitter @laurazig or by email at lauraz@kcur.org.