Middle schoolers in the Kansas City area are paying close attention to Greta Thunberg and other youth climate activists making waves across the world. They’re also proposing their own solutions for global warming.

“I like to see kids taking action about what might happen in the future,” said Liam McKinley, an eighth grader at Chisholm Trail Middle School in Olathe. “I like to come up with random ideas about how we can fix that, even though it might not be achievable in the next few years.”

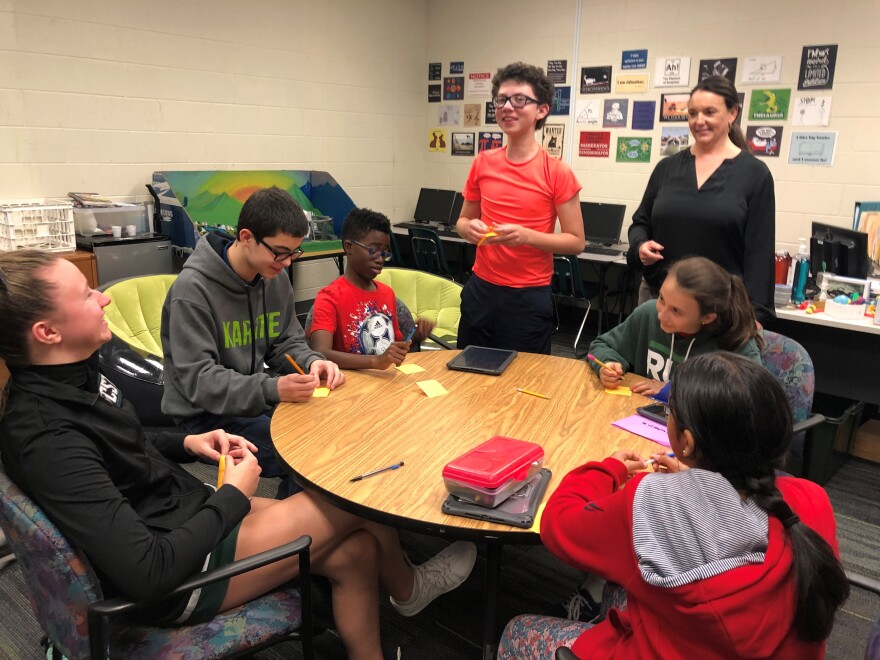

That’s why Liam joined the school’s Future Cities team, which is coached by Deonne Hobson.

“We’ve looked at stormwater management, we’ve looked at farming issues,” Hobson said. “This year, they have to identify problems with water sourcing and supply and then propose futuristic solutions to the problem.”

Yet, students don’t have to imagine a future where nothing happens when you turn on the tap. It’s already happened in California and across the Southwest. Closer to home, farmers in western Kansas are rationing water as the Ogallala Aquifer dries up.

Young people are noticing the issues, too, Hobson said.

“They’re paying more attention than we give them credit for sometimes,” she said. “Especially the particularly bright ones, who are able to see, ‘Hey, that’s something that could impact me.’”

That’s definitely Liam, who said tries to keep up with the latest news, though it sometimes gets him in trouble.

“Whenever I hear something about the environment and clean energy, I always try to listen in,” said Liam, smiling slightly, “even when my parents are talking to me.”

Kansas’ regional Future Cities competition is in January. It’s like a science fair, but the students do a lot more than build a paper mâché volcano and fill it with vinegar and baking soda. Liam has been researching hydroelectricity and nuclear fusion.

His teammate, fellow Chisholm Trail eighth grader Mary Glasgow, wants to incorporate vertical farming into their model city for the Future Cities competition.

“Last year was building a reliable power grid that can withstand natural disasters. I knew absolutely nothing about it,” Glasgow said. “I find it really interesting to learn new topics and expand my horizons.”

Hobson’s gifted classroom is a safe space where students can really nerd out. No one is going to tell them they’re “too smart,” Hobson said.

“They're a little more willing to share their ideas because they don't feel like there's going to be as much judgment, she said.

As a result, kids get into some pretty adult conversations while they work on solutions for Future Cities, including the politics that invariably surround climate change, which Hobson said is a “fine line.”

“Things like climate where there's hard science to back it up, I'm pretty upfront. ‘This is what the science supports, and this is what's going on,’” she said. “I don't shy away from that very much.”

Scientific consensus

Last year, the National Science Teaching Association published a position paper on teaching climate science. It reads, in part: “Given the solid scientific foundation on which climate change science rests, any controversies regarding climate change and human-caused contributions to climate change that are based on social, economic, or political arguments — rather than scientific arguments — should not be part of a science curriculum.”

The executive director of NSTA, oceanographer David Evans, said that many of the educators who worked on the position paper wanted to include an oft-cited statistic that 97% of all climate scientists agree that humans are causing global warming.

It’s not in there.

“If you make a statement like that, what you’re suggesting is that science depends on how many people would vote for it. But you know, if 50% of people said that Newton’s law of gravitation was wrong, it wouldn’t change the fact that when I drop a pencil, it’s going to fall,” Evans said.

Related content — Climate Change 101: A Kansas City Scientist Explains What's Going On

Evans also said there’s a shift underway in how science is taught. NSTA urges teachers to start with the scientific phenomena, like a smell, a taste, a loud sound.

“Something that a student can experience,” Evans explained. “Then, encourage the student to begin the process of developing an explanation. That’s a complete turnaround from the way I learned science when I was young. That always began with things like definitions and paragraphs of reading, then maybe later on there was an experiment that would demonstrate something.”

When it comes to teaching climate change, Evans said teachers have an advantage because even very young children can experience weather and the changing seasons. Helping students understand the climate system is completely within science teachers’ purview.

“In my ideal world,” Evans said, “we would team teach climate change with a science teacher and a social studies teacher because even given what we know about climate change, the next step of what we do is really a political or a social question.”

Throughout the month of November, KCUR is taking a hard look at how climate change is affecting (or will affect) the Kansas City metro region.

Elle Moxley covers education for KCUR. You can reach her on Twitter @ellemoxley.