The changes in climate that people in the Kansas City region are now experiencing haven't been seen in previous lifetimes.

That's according to Doug Kluck, a regional climate services director for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). He also spent 18 years with the National Weather Service as a researcher and forecaster.

KCUR recently sat down with Kluck in an effort to provide readers with some perspective on what's happening. Below is the edited version of that conversation.

Q: People maybe think they know, but maybe they aren't totally sure: What is climate change? What are the easy ways to describe climate change?

A: Well, the easiest thing to say is that the earth is always going through some sort of shift or change in climate over a long, long, long periods of time. … The glaciers that occurred about 10,000 years ago or so took thousands of years to form and move and all of that. But what we're seeing in our lifetime is sort of an enhanced climate change. In other words, it's happening relatively quickly compared to other times in the past.

The only other time we've seen climate change this abrupt is when a meteor strikes the earth. And that's very abrupt. And that's more or less overnight, and cataclysmic. This is slower than that, but yet faster than, let's say, most natural means.

Q: And is it accelerating?

A: That's probably debatable. It certainly has accelerated since the middle part of the 20th century. And we see, in terms of the temperatures like in the ocean and on land, when you combine the last 10 years as a whole, it's never been warmer in our period of record, which stretches back several hundred years.

Q: With climate change itself, we're speaking solely weather and how weather affects the planet?

A: Weather is what happens today … sort of what happens in your backyard. Climate change is sort of what happens globally over a big, large — much larger area than even the middle part of the United States.

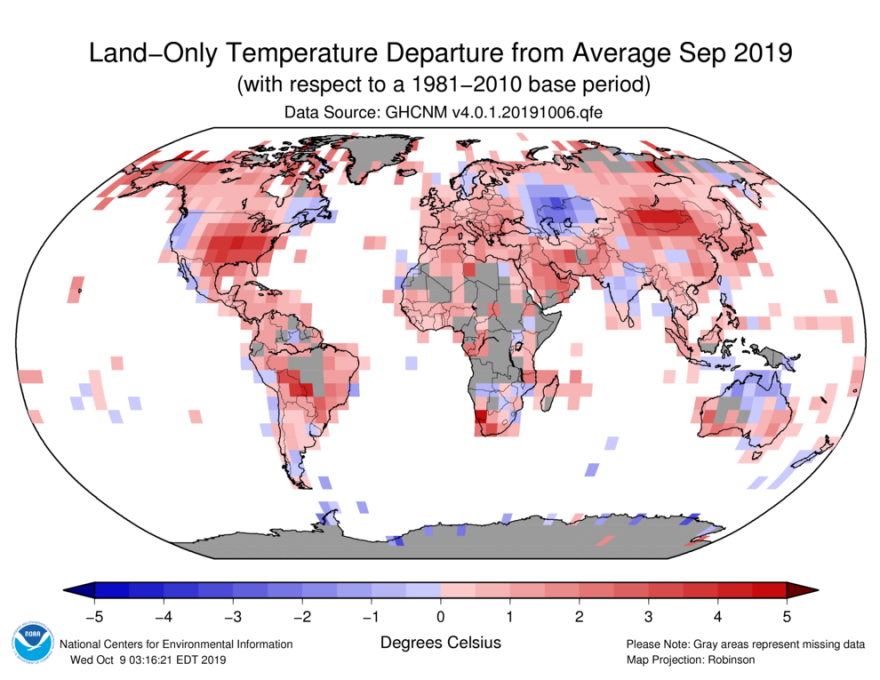

So if you'd look at a map, for example, of let's say average temperatures for the world for September: You would see a pink and blue map. The pink indicates where it's warmer than normal. The blue indicates where it's cooler. Invariably, there is a dominance of pink and red colors and has been that way for the last 10 or 20 years. It's very rare now that we see blue. In other words, cooler than normal temperatures dominate a map of a monthly average temperature.

Q: What isn't climate change?

A: Some people think that climate change means always warming, which again isn't true. We look outside today, we see today's temperatures are below normal. We're still going to have winter, even with climate change.

What we've noticed though is that, for example, that our minimum temperatures don't get as cold as they used to. Our temperatures in the summer — you may say, “Oh my goodness, it's hotter than heck, and it has been for a long time.” But, really, our high temperatures in the summer haven't seen, especially in Missouri, in the Southeast part of the U.S., haven't really seen a steep incline like the minimum temperatures.

The other thing people ask me is, do you believe in climate change? And I often say in response I don't see climate change as a belief system so much as a scientific issue. And from the science that I understand and know, the science is telling me that climate is changing. So it's not a question in my mind whether it's happening or not, but people like the idea of believing in something. Well, that's the overpoliticization of the topic, to be honest.

Q: Why is it important to discuss climate change?

A: Whenever I talk to groups of people — whether they're in agriculture or whether they're municipalities or another federal agency, a tribal nation — there's always interest in planning. There's a long-term planning, short-term planning, medium-range planning; and I guess short term would be within the year, a medium would be 5-10 years and long-term planning would be 20-plus years.

And it really depends on what you're interested in building an infrastructure-wise. Often that's a big deal: People want to know, well, is this kind of rain, this kind of flooding going to be normal or more normal in the future? And often the answer is yes, this is a shape of things to come in terms of flash flooding, as well as some of the river flooding that we're seeing.

Q: So, the importance is for preparation, prevention and possibly solutions?

A: Correct. We also keep track of extreme events at the National Centers for Environmental Information. And if they hit $1 billion of damage, they get recorded. It doesn't mean all the other ones aren't important, but once we hit $1 billion, we try to keep track of those and see over the period of years and keep the values the same — in other words, we normalize the damage to some standard value.

If you look at that since 1980, there has been a trend of more and more $1 billion extreme events occurring. When those happen, like happened and is happening along the Missouri River this year and tributaries, people take notice — and not just people live along the river; politicians, elected officials, everybody seems to care a lot more during extreme events. They all are interested in understanding how often this is going to happen, whether this is attributable to climate change — because they need to know for their planning aspects.

We don't know the worst it can be. We speculate, and that's important, but then when you add sort of the icing on the cake of climate change that ups the numbers even more than you used to.

Q: Are you guys thinking that at some point you're going to have to move that $1 billion threshold higher?

A: I think they're going to keep it at a billion. What's interesting about it, if you look at where those cases are, they're vulnerable areas like coastlines. So when we say $1 billion dollar events, we're talking about tropical systems, we're talking about tornadoes and hail, drought, flooding and several other things … all those kind of wrapped into extremes. … So in other words, it's easier in Texas, in Houston, to cause a billion dollars of damage than it is in Fargo.

Q: Is there any common language that you use or your colleagues use that could be confusing for people when it comes to climate change?

A: We as scientists tend to be technical and relatively conservative when it comes to our use of language in our predictions and all that kind of stuff. It’s rare that we go out on a limb and say, “Oh, well there's going to be an extreme event next week.” Occasionally we do. And if we see it, we will start making overtures, and people like TV personalities — meteorologists and such — will pick that up and start using it as well, which is fine because we do want to tell people that conditions are such or may become pretty bad.

We're still worried, for example, about the whole Missouri River basin. Soil moisture in the Missouri basin for the most part is well above normal for this time of year. So what that means is we're probably going to freeze a lot of that moisture in the soil. And it's not going to drain out like it would in the summer, or be evaporated or be evotranspirated by plants. So what we have now in the soils is kind of locked in until next spring.

Well, why is that a big deal? Well, spring is where we see the heavy rainfalls and we see a lot of snowmelt — Plains snowmelt as well as mountain snowmelt. So … we're saying about the Missouri River basin is, we’re primed for similar, maybe even worse, (flooding) than we were going into the fall last year.

And we saw what happened in beginning in March of last year after the cold broke: We had lots of rain. We had frozen soils, we had snowmelt. All that contributed to a massive flood in Nebraska of South Dakota, Missouri, Iowa.

It's not really not a climate change issue so much as an alerting for long-term weather or climate, however you want to look at that.

Q: OK, so not a climate change issue, but possibly exacerbated by it. This is kind of the divide, right? What we're trying to figure out is just what it is and what it isn't, and when can you point to it and go, “definitely, this is it.”

A: I like to say these events are going to happen in any case. What climate change may be introducing to it is a 1-5% or 1-10% additional precipitation or snow … or a temperature flux or variation.

There's a whole bunch of guys who do climate research for a living that do this attribution work. That's where they go back, look at an event and say, “OK, let's pull this apart as best we can and determine, okay, was this El Nino, La Nina? Can we point our finger at something else and say, it's the cause? And/or can we say climate change had an impact on this?”

So, often climate change is this sort of slowly developing impact, which adds a certain percent to many particular extreme events. It's like icing on a cake. Along the coast, that can make the difference. One more foot and you flooded a lot more land. It really can make a big difference.

Q: Are there ways to address the philosophical issue of climate change without using the phrase? I do think it may … it scares people.

A: So again, depending on what audience you're talking to, and it's important to know your audience as well as you can. Some audiences, you can ask them without getting into the climate change business, just simply ask them what they've seen. What's changed in the last 20 years?

Let’s say agriculture: Have you been able to plant longer-season varieties? And the answer is almost invariably yes. Is it wetter than it used to be? Almost invariably, yes. Not always, but most of the time.

But linking it necessarily to anthropogenic climate change is often a tough leap for people. And I understand, you can't just point at something and say, “OK, we're having more weeds because of climate change” or “We’re having more rain because of human-caused climate change.”

It is true that it is probably happening because of that, but it really depends on the audience. And there are things that they will want to know that would help remedy that situation to a degree. … there's a whole soil health initiative out there, for example … almost everything is fairly positive about it.

If you can get folks to adapt some of those methods, we don't need to talk about climate change. We're still moving ahead in the right way.

Q: Are you ever concerned, given that you work under an administration that that doesn't necessarily acknowledge climate change, about putting out reports and talking about it publicly?

A: Personally, no, I'm not. Others may be, but I work for a great agency that allows us to do our jobs. And again, we talk about climate across timescales and across geographies, so people are very interested in that and it doesn't matter what side of the aisle you come down on. … That whole resiliency thing keeps people working together on a lot of these issues, especially locally and regionally.

Q: How worried should people be about climate change?

A: Probably more worried than we are. Pretty much. Yeah. As a society, definitely more worried than we are.

Q: What do you want to emphasize out of this conversation?

A: Well, I would say this: Climate change isn't necessarily the end of the world and there are there are positives, there are benefits. You can go ask the agriculturalists this question: What are the benefits you've seen? Longer growing season is one of them. … I would say we all need to be conscious of our activities and who we elect and all that kind of business as well.

It's not a belief system. It is a scientific sort of fact, so don't politicize it. Just use it to your advantage. Make sure you take it into account, especially municipalities and other folks that build. Don't build by a river, don't build by an ocean. Be careful of those kinds of things.

For more information, Kluck suggested reading the National Climate Assessment, volumes I and II.

Throughout the month of November, KCUR is taking a hard look at how climate change is affecting (or will affect) the Kansas City metro region.

Erica Hunzinger is an editor with KCUR and the Kansas News Service. Follow her on Twitter: @ehunzinger.