For more stories like this one, subscribe to A People's History of Kansas City on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Andrea Broomfield hated Hydrox cookies as a kid.

“Like most kids growing up in suburbia Kansas City, we loved Oreos more than Hydrox because Hydrox cookies seemed like they were boring," says Broomfield. "Like, the flavor was boring.”

Today, Broomfield is the author of several Kansas City food history books. But when she was growing up, she had no idea that Hydrox was created by a company in her own hometown — nor did she particularly care.

“The name seemed stupid to us," she remembers. "The Hydrox font and packaging looked boring to me. Hydrox looked like something that my grandmother would eat."

This is the way many people remember Hydrox.

Over the last century, Hydrox have become the edible embodiment of what it means to be second-best in America. The spirit cookie of vice presidents and silver medalists. The cheap, certifiably uncool Xerox of an Oreo.

There’s a problem with that narrative, though. Hydrox aren’t a knockoff — they’re the original sandwich cookie.

Hydrox debuted in 1908, a full four years before Oreo came out, and they were revolutionary at the time.

They also taste pretty dang good.

"I feel like Hydrox is the underdog sandwich cookie," says KCUR reporter Frank Morris, who grew up eating Hydrox and liking them. "A Hydrox cookie, the cookie part, tastes sharper. It's got a much more sophisticated taste than an Oreo."

So why is it that a century later, one cookie is America’s favorite, while the other is mostly pulled out as a clue for crosswords and trivia contests?

‘The biscuit war’

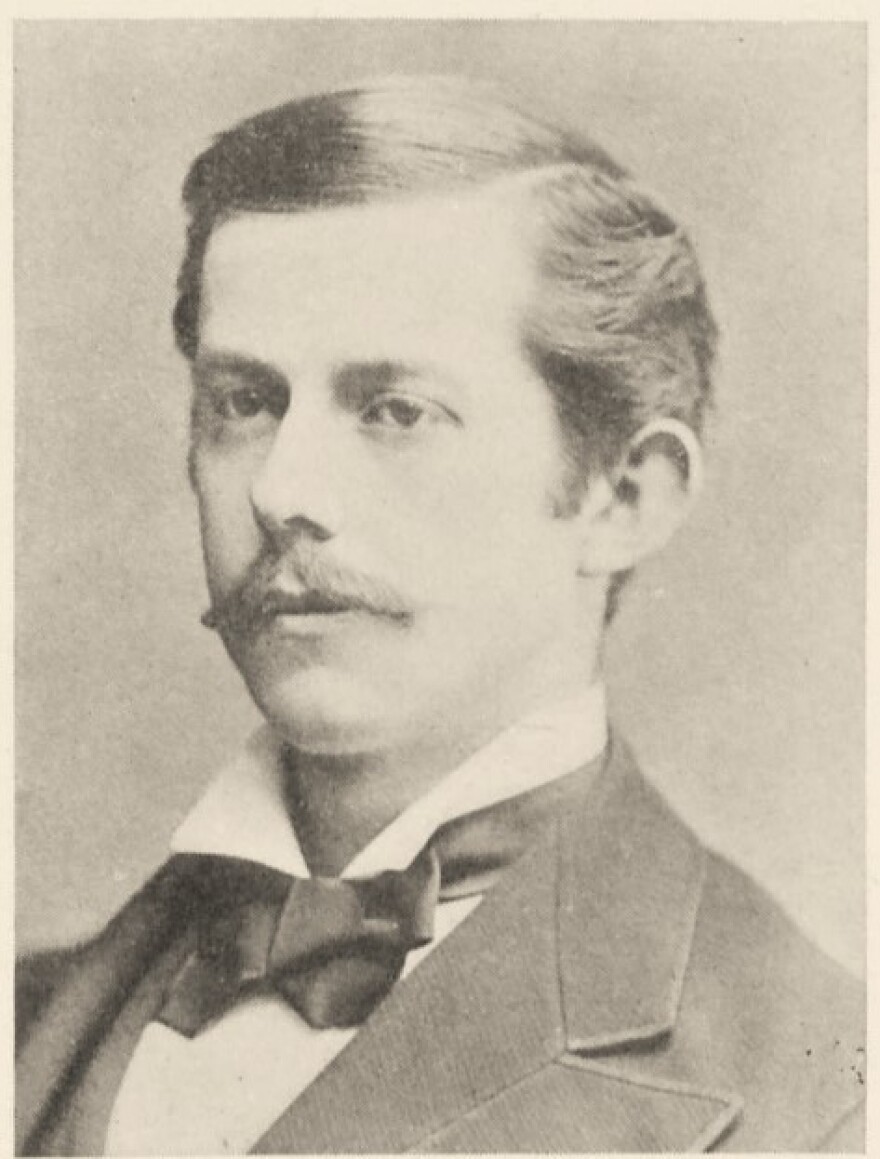

Both of these cookies — Hydrox and Oreo — can be traced back to a man named Jacob Loose.

That name might ring a bell for Kansas Citians. Loose Park in Brookside was donated to the city in honor of Jacob Loose, who by the end of his life was a prolific philanthropist.

He first arrived in southeastern Kansas back in 1870, as an ambitious 20-year-old, to get into the dry goods business.

In 1882, Jacob Loose and his brother Joseph purchased a controlling interest of the Corle Cracker and Confectionary Company in Kansas City, Missouri, and changed its name to Loose Brothers Manufacturing Co.

“Jacob — I see him as the driver. He seemed to be very interested in… achieving something,” says Stella Parks, a pastry chef and author of the cookbook, BraveTart.

At the time, manufactured crackers and cookies were just starting to pop up in America — including some now-universal treats like Fig Newtons and sugar wafers.

In 1890, Jacob decides to eliminate his competition by uniting bakeries across the Midwest under one roof. He hires a bigshot Chicago lawyer, Adolphus Green, to bring his idea to fruition.

Together, 35 or so bakeries form the American Biscuit and Manufacturing Company. Jacob becomes the president. Joseph is appointed to the board of directors, and Adolphus becomes the general counsel.

But American Biscuit Co. doesn’t have a total monopoly, exactly. There are two other big, national bakery corporations: the United States Baking Co. and the New York Biscuit Co.

For the next seven years, the three companies duke it out in the market — constantly trying to one up each other in what comes to be known as the "biscuit war."

In 1897, poor health forces Jacob Loose to step down as president, leaving Joseph Loose and Adolphus Green more-or-less in charge of American Biscuit Co. Against Jacob’s wishes, they merge the company with its fiercest competitors in 1899, forming a powerhouse called the National Biscuit Company.

Today, you might know it better by the name Nabisco.

“Joseph was the one who was really interested in the notion of creating a bigger trust," Broomfield says. "Whereas Jacob was not, and since he was sick and convalescing in Europe, he couldn't really do much about what Joseph was doing.”

Jacob Loose — who at this point is extremely rich — eventually recovers from his illness. He comes home to Kansas City to a completely new cookie landscape.

Bitter about the power grab that transpired while he was away, Jacob announces that he will directly compete with Nabisco.

In 1902, Jacob forms the Loose-Wiles Biscuit Company with his brother Joseph and a Kansas City candy businessman named John Wiles.

“[Loose] is very popular with the trade and is the best known bakery magnate in the country," wrote the Wall Street Journal. "His competition is regarded as rather serious to the National interests."

Over the next six months, 40 or so employees quit Nabisco to go work for Jacob Loose. And the war between Loose-Wiles and Nabisco ramps up.

“The two companies were constantly trying to compete by offering very similar types of cookies or biscuits," Broomfield explains. "The famous Nabisco biscuit was called Uneeda and Loose Wiles responded with Takoma. So, you-need-a biscuit, or, take-home-a biscuit."

A beloved biscuit is born

Jacob Loose needed something special and innovative to give his products the edge — and he found it in the form of chocolate.

Chocolate wasn't always as ubiquitous a flavor as it is now. Cacao is native to Central and South America, and it became a delicacy of the rich in Europe and North America over centuries of colonization.

It wasn’t until the mid-to-late 1800s that, with improved importing, innovations like cocoa powder and milk chocolate made chocolate more widely accessible and affordable.

The Loose brothers want to capitalize on this trend, and so in 1908 they put two crisp, bitter dark chocolate wafers around a layer of sweet vanilla creme.

They called their creation Hydrox. It was America’s first chocolate sandwich cookie.

“The Hydrox had this really elaborate laurel wreath and this really elaborate font," Parks says. "It was a very baroque little cookie."

Hydrox wasn’t intended to be an everyday cookie, but rather a special event. Advertisements billed it as the "aristocrat of cookies," with an embossed design that stood out from other animal-shaped cookies.

Hydrox especially took off at soda shops and pharmacies, and helped propel Loose-Wiles to success.

Loose-Wiles, which eventually rebranded as Sunshine Biscuits, became famous over the next few years for American icons like Cheez-Its, Lemon Coolers, and Vienna Fingers.

The name Hydrox might seem more chemical than confectionary today — an odd choice if you want to sell something as delicious and upscale. But Parks says the branding fit, at the time, into America’s obsession with food sanitation: “It's supposed to be like hydrogen and oxygen are these pure clean elements. There's nothing cleaner. There's nothing finer.”

At a time when most Americans thought of factories as dirty and unsafe places to work, Loose-Wiles was trying to be a clear outlier. Before long, Loose-Wiles had beautiful, sunlit factories in Kansas City, Minneapolis, Dallas, St. Louis, Chicago and Boston.

"I really have a lot of admiration for Jacob Loose," says Parks. "He wanted to bring all this light into the work floor."

In 1912, Loose-Wiles debuted its brand new "Thousand Window" bakery in Long Island City, New York, which held the distinction of being the world’s largest bakery for more than 40 years.

“It is impossible to go through that wonderfully tiled, perfectly ventilated, sunlit institution, with every modern sanitary device installed… without paying tribute to the genius which has devised it,” a New York Globe journalist wrote a few years later.

Naturally, Nabisco responds by building its own, enormous bakery in Manhattan. By this time, the company’s president is none other than Jacob Loose's former business associate, Adolphus Green.

Loose-Wiles is still a relative underdog to the massive conglomeration of Nabisco. In 1912, Loose-Wiles made a mere $12 million in sales compared to Nabisco’s $45 million.

But they were still seen as a real competitor, especially with Hydrox now on the market.

"There was a publication called the United States Investor and they had this one article. The headline was 'Exchange National for Loose Wiles?' So they're literally saying like, abandon your stocks at Nabisco. Loose Wiles is pulling ahead here," says Parks.

Nabisco needed its own product to fight back. So that same year, Adolphus Green and Nabisco unveiled their own sandwich cookie: the Oreo Biscuit.

It was advertised as "two beautifully embossed chocolate flavored wafers with a rich cream filling," and sold for 30 cents a pound.

“Not only was Oreo this copycat of Hydrox, it was also built on the back of the company that Jacob had founded himself,” says Parks.

Loose-Wiles tried to innovate in other ways. It joined forces with the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America and created the country’s first kosher certification program.

That also gave Hydrox a hold on the Jewish market — Oreos weren't certified kosher until 70 years later, when they stopped being made with lard.

For years, the two cookies duked it out. But in 1922, Joseph Loose dies, and his brother Jacob passes away the year after.

The following years are marked by a rotation of leaders at Loose-Wiles, a number of high-profile labor strikes, and declining sales of Hydrox.

A clear winner between the two cookies became apparent in the 1950s. That's when Nabisco increased the price of Oreos, something that Stella Parks called reverse psychology at its finest.

“Americans didn't flock to the suddenly affordable Hydrox; they shunned it as cheap in every sense of the word — the kind of low-budget, fuddy-duddy knockoff favored by penny-pinching grandpas,” she writes.

Hydrox starts to be seen as Oreo's budget-friendly, off-brand alternative. On top of that, Parks says the name Hydrox wasn’t even properly trademarked — which made it really hard to cultivate any kind of strong brand recognition.

“There were lots of other products called Hydrox on the market, from table water to like literal bottles of hydrogen peroxide,” Parks says.

Loose-Wiles' advertising also took a slightly grumpy tone, constantly reminding people who was the "original" creme-filled sandwich cookie.

"Once Oreo came out, all the Hydrox advertisements had this really, like, whiny quality to them," Parks says. "Like, 'we’re first!'"

None of it made Hydrox seem cool.

1966 was the beginning of the end. Sunshine Biscuits was acquired by its first company in a long string of new owners — all of which tweaked the marketing, the formula, or rebranded Hydrox completely.

Kellogg's more-or-less pulled the plug on the brand in 2003, much to the disappointment of hoards of dedicated fans.

"This is a dark time in cookie history," wrote Gary Nadeau of O'Fallon, Missouri, on a website devoted to Hydrox in 2007. "And for those of you who say, 'Get over it, it's only a cookie,' you have not lived until you have tasted a Hydrox."

Thankfully, for fans like Gary Nadeau, one man decided to bring Hydrox back from the dead.

The return of Hydrox

Something you should know about Ellia Kassoff is that he is an extremely nostalgic person. Kassoff grew up in Palm Springs, California, a land of hot springs, manicured golf courses and vacation-getaway weather.

“I had great memories of high school. I mean, I was the head of our high school reunion,” he said recently. “Because that’s my passion.”

Around 2010, Kassoff went all-in on nostalgia when he became the CEO of Leaf Brands LLC, a company that made its mark by reviving and selling iconic snack foods and candies long gone from the shelves.

"Look, everyone hates change," Kassoff says. "If I can slow that down in certain aspects of people's lives, then I've done my job."

First, Kassoff resurrected Astro Pops, his favorite cone-shaped lollipop from childhood. Then there were Wacky Wafers and tart n' tinys.

“I just said to myself, 'What other favorite candies did I have as a kid that would help me bring back my own memories of childhood that are no longer being made?'” Kassoff said.

The Kassoffs were one of the first Jewish families in Palm Springs — and that means they were strictly a Hydrox family. Never Oreos.

By the 2010s, Hydrox was still owned by Kellogg's. However, Kassoff realized he could potentially claim the trademark for himself if he could prove that Kellogg's wasn't planning on using it.

One of his tricks, as detailed in NPR's Planet Money podcast, was to pose as a customer trying to buy Hydrox in order to get Kellogg's to admit they had no plans on making any more.

Once he secured the trademark for Hydrox, though, Kassoff was still at square one in a lot of ways. It’s not like someone gave him the secret formula.

In order to crack the Hydrox recipe, he sourced an unopened 1998 box of Hydrox on Craigslist and teamed up with a food scientist to recreate the sandwich cookie of his boyhood dreams. And he recruited a ton of Hydrox superfans to taste test the prototypes — and provide detailed feedback about the flavor and texture.

"We had the A, B, and C samples and we asked them, 'Please try them out. Tell us what you're thinking,'" says Kassoff. "And there was one of the samples... that was pretty much almost unanimous."

Finally, in 2015, Kassoff's Leaf Brands relaunched Hydrox, to much national fanfare.

“When it first came back, I ordered like five packages so I could give everyone in my family a package,” says Kansas City resident Kathy Greuter.

More than a century after its initial creation, though, Hydrox is just one of many chocolate sandwich cookies in today’s supermarkets — including Newman-O's, Joe-Joe's, and countless others. That is, if you can find it there.

Kassoff says it's been tough to get buy-in and placement at mainstream stores; their biggest distributor right now is Amazon.

That's been one constant over the cookie's many iterations: Hydrox's bitter rivalry with its imitators.

Kassoff personally blames Big Oreo for his grocery store woes. Specifically, Kassoff alleges that workers for Mondelez, the parent company of Nabisco, are coming into groceries and hiding Hydrox on higher-up shelves where they’re not supposed to be.

That makes it difficult for customers to find, and less likely to purchase, Hydrox.

“I guess it's a thing where the big guys — they go in and they hide the competitor's product or they’ll spray each other's products with sodas. Nobody wants to buy it,” says Kassoff. “And so we have enough of that, that now we're waiting to see what the government does.”

In 2018, Leaf Brands filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission asking Mondelez for $800 million in damages. Kassoff is still waiting for a formal response.

“As we have stated numerous times in the past and in numerous forums when Hydrox raises these allegations," said a Mondelez spokesperson in response. "Our shelf placement in stores stems from the fact that Oreo is the No. 1 cookie in the US, loved by consumers, and retailers.”

One of the only consistent in-person places to get Hydrox these days is Cracker Barrel. In fact, when this reporter went to her closest Cracker Barrel — outside of Kansas City in Independence — there were only three boxes left.

"We have a hard time keeping them in stock," says employee Ginny Neale, who turned out to be a Hydrox fan herself. "People will come to Cracker Barrel just to get them."

A rivalry this long-running feels almost too dramatic to be real, but people are serious about these cookies. And, like Kassoff, it goes back to their childhoods.

"My mother worked as a teller at Westport Bank. She didn't have any money. I think she made $40 a week," says Mary Elizabeth Lewis, who grew up in Kansas City. "So sandwich cookies were a big, big treat... It was something we would have maybe once every couple of months."

I asked Lewis what she thought of the taste of Hydrox, the cookie she and her mother preferred to Oreos.

“Maybe I'm being far too serious, but a lot of times, it's not just the Hydrox cookie. It's the story around it. It's the feeling you get,” she says. “For me, it means a mother's love and sacrifice. It's not the cookie. It's what the cookie meant.”

This episode of A People's History of Kansas City was reported, produced and mixed by Mackenzie Martin with editing by Gabe Rosenberg.