Inga Selders, a city council member in a suburb of Kansas City, wanted to know if there were provisions preventing homeowners from legally having backyard chickens. So she combed through deeds in the county recorder's office for two days looking for specific language.

At one point, she stumbled across some language, but it had nothing to do with chickens.

"I heard the rumors, and there it was," Selders recalled. "It was disgusting. It made my stomach turn to see it there in black-and-white."

What Selders found was a racially restrictive covenant in the Prairie Village Homeowners Association property records that says, "None of said land may be conveyed to, used, owned, or occupied by negroes as owners or tenants." The covenant applied to all 1,700 homes in the homeowners association, she said.

"There's still racism very much alive and well in Prairie Village," Selders said about her tony bedroom community in Johnson County, Kan., the wealthiest county in a state where more than 85% of the population is white.

The racially restrictive covenant that Selders uncovered can be found on the books in nearly every state in the U.S., according to an examination by NPR, KPBS, St. Louis Public Radio, WBEZ and inewsource, a nonprofit investigative journalism site. Although the Supreme Court ruled the covenants unenforceable in 1948 and although the passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act outlawed them, the hurtful, offensive language still exists — an ugly reminder of the country's racist past.

"I'd be surprised to find any city that did not have restrictive covenants," said LaDale Winling, a historian and expert on housing discrimination who teaches at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg.

While most of the covenants throughout the country were written to keep Blacks from moving into certain neighborhoods — unless they were servants — many targeted other ethnic and religious groups, such as Asian Americans and Jews, records show.

In this moment of racial reckoning, keeping the covenants on the books perpetuates segregation and is an affront to people who are living in homes and neighborhoods where they have not been wanted, some say. The challenge now is figuring out how to bury the hatred without erasing history. In some instances, trying to remove a covenant — or its racially charged language — is a bureaucratic nightmare; in other cases, it can be politically unpopular.

Loading...

For Maria Cisneros, it was painfully difficult. Cisneros, the city attorney for Golden Valley, a Minneapolis suburb, found a racially restrictive covenant in her property records in 2019 when she and her Venezuelan husband did a title search on a house they had bought a few years earlier.

"I was super-surprised," she said. "If anyone should have known about this, I should have. I'm an attorney."

Cisneros, who is white, said she wanted the covenant removed immediately and went to the county recorder's office. What she thought would be a simple process actually was cumbersome, expensive and time-consuming. She took time off work and had to get access to a private subscription service typically available only to title companies and real estate lawyers. There were forms to fill out that required her to know how property records work. She also had to pay for every document she filed.

"It took hours — and I'm a lawyer," she said. "I don't think any non-lawyer is going to want to do this."

In the end, Cisneros learned that the offensive language couldn't be removed. That is often the case in other cities if officials there believe that it's wrong to erase a covenant from the public record. Instead, the county agreed to attach a piece of paper to Cisneros' covenant disavowing the language.

"A lot of people don't know about racial covenants," she said, adding that her husband and their four children are the first nonwhite family in their neighborhood. "A lot of people are shocked when they hear about them."

After her ordeal, Cisneros started Just Deeds, a coalition of attorneys and others who work together to help homeowners file the paperwork to rid the discriminatory language from their property records.

"It's complicated stuff," she said.

It's impossible to know exactly how many racially restrictive covenants remain on the books throughout the U.S., though Winling and others who study the issue estimate there are millions. The more than 3,000 counties throughout the U.S. maintain land records, and each has a different way of recording and searching for them. Some counties, such as San Diego County and Hennepin County, which includes Minneapolis, have digitized their records, making it easier to find the outlawed covenants. But in most counties, property records are still paper documents that sit in file cabinets and on shelves. In Cook County, Illinois, for instance, finding one deed with a covenant means poring through ledgers in the windowless basement room of the county recorder's office in downtown Chicago. It's a painstaking process that can take hours to yield one result.

Cook County Clerk Karen Yarbrough, whose office houses all county deeds, said she has known about racial covenants in property records since the 1970s, when she first saw one while selling real estate in suburban Chicago. She called them "straight-up wrong."

"I see them and I just shake my head," she said in an interview with NPR. "Those things should not be there."

While the covenants have existed for decades, they've become a forgotten piece of history.

Desmond Odugu, chairman of the education department at Lake Forest College in Illinois, has documented the history of racial residential segregation and where racial covenants exist in the Chicago area. He said he was stunned to learn "how widespread they were."

"The image of the U.S. I had was a post-racial society," said Odugu, who's from Nigeria. "But as soon as I got to the U.S., it was clear that was not the case. I had a lot to learn."

Odugu said he has confirmed 220 subdivisions — home to thousands of people — in Cook County whose records contain the covenants.

"It only scratches the surface," he said.

A dark history

When the Great Migration began around 1915, Black Southerners started moving in droves to the Northeast, Midwest and West. Their hope was for a better life, far away from the Jim Crow laws imposed on them by Southern lawmakers. Blacks soon realized, though, that segregation and racism awaited them in places like Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles, particularly in housing. They often were forced to live in overcrowded and substandard housing because white neighborhoods didn't want them.

Chicago, which has a long history of racial segregation in housing, played an outsize role in the spread of restrictive covenants. It served as the headquarters of the National Association of Real Estate Boards, which was a "clearinghouse" for ideas about real estate practice, Winling said.

"This was kind of ... like a nerve center for both centralizing and accumulating ideas about real estate practice and then sending them out to individual boards and chapters throughout the country," he said.

In 1917, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that local governments could not explicitly create racial zones like those in apartheid South Africa, for example. But another Supreme Court case nine years later upheld racial covenants on properties. In Corrigan v. Buckley, the high court ruled that a racially restrictive covenant in a specific Washington, D.C., neighborhood was a legally binding document between private parties, meaning that if someone sold a house to Blacks, it voided the contract, Winling said. That ruling paved the way for racially restrictive covenants around the country. In Chicago, for instance, the general counsel of the National Association of Real Estate Boards created a covenant template with a message to real estate agents and developers from Philadelphia to Spokane, Wash., to use it in communities.

"So we see a standardization and then intensification of the use of covenants after 1926 and 1927 when the model covenant is created," Winling said.

Chicago also was home to one of the earliest landmark restrictive-covenant cases in the country: Hansberry v. Lee. Carl Hansberry, a Black real estate broker and father of playwright Lorraine Hansberry, bought a home in the all-white Woodlawn neighborhood on the city's South Side in 1937. After a neighbor objected, the case went to court — ultimately ending up before the U.S. Supreme Court. Hansberry prevailed. The 1940 decision eventually led to the demise of the racist legal tool by encouraging more legal challenges against racial covenants. The family never returned to the three-story brick home now known as the Lorraine Hansberry House, and renters now occupy the run-down property. The city designated it a landmark in 2010.

Meanwhile, in south St. Louis, developers baked racial restrictions into plans for quiet, tree-lined subdivisions, ensuring that Black — and in some communities, Asian American — families would not become part of these new neighborhoods.

That all changed in 1948 when J.D. and Ethel Shelley successfully challenged a racial covenant on their home in the Greater Ville neighborhood in conjunction with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. The family, like countless other Blacks, had come to St. Louis from Mississippi as part of the migration movement. After buying a home from someone who decided not to enforce the racial covenant, a white neighbor objected. The man sued the Shelleys and eventually won, prompting them to appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that the state could not enforce racial covenants. The landmark civil rights case became known as Shelley v. Kraemer.

But things didn't change overnight.

"After Shelley versus Kraemer, no one goes through and stamps 'unenforceable' in every covenant," said Colin Gordon, a history professor at the University of Iowa. "They just sit there."

About 30,000 properties in St. Louis still have racially restrictive covenants on the books, about a quarter of the city's housing stock in the 1950s, said Gordon, who worked with a team of local organizations and students to comb through the records and understand how they shaped the city. Another 61,000 properties in St. Louis County continue to have the covenants, he said.

Dealing with the past

Past the heavy wooden doors inside the Land Records Department at St. Louis City Hall, Shemia Reese strained to make out words written in 1925 in tight, loopy cursive. Time has relegated the document to microfilm available only on the department's machine. She used her finger to skim past the restrictions barring any "slaughterhouse, junk shop or rag picking establishment" on her street, stopping when she found what she had come to see: a city "Real Estate Exchange Restriction Agreement" that didn't allow homeowners to "sell, convey, lease or rent to a negro or negroes." The covenant applied to several properties on Reese's block and was signed by homeowners who didn't want Blacks moving in.

Reese, who is Black, said her heart sank at those words, especially because buying her home in the JeffVanderLou neighborhood in north St. Louis 16 years ago is something of which she is proud.

"To know that I own a property that has this language ... it's heartbreaking," Reese said. "This is the part of history that doesn't change. And so when people say, 'We don't have to deal with our past,' this right here lets you know that we definitely have to deal with it."

To Reese, that means having hard conversations about that history with her children, friends and neighbors. She plans to frame the covenant and hang it in her home as evidence of systemic racism that needs to be addressed.

"People will try to say things didn't happen or they weren't as bad as they seem," Reese said. "It's always downplayed."

But other St. Louis homeowners whose property records bear similar offensive language say they don't understand the need to have a constant reminder.

"It bothers me that this is attached to my house, that someone could look it up," said Mary Boller, a white resident who lives in the Princeton Heights neighborhood in south St. Louis. "I want to take a Sharpie and mark through this so no one can see this."

Gordon argues that racially restrictive covenants are the "original sin" of segregation in America and are largely responsible for the racial wealth gap that exists today.

"And the fact that of similarly situated African American and white families in a city like St. Louis, one has three generations of homeownership and home equity under their belt, and the other doesn't," he said. "It's a huge difference to your opportunities."

Gordon said the covenants are not mere artifacts of a painful past. They laid the foundation for other discriminatory practices, such as zoning and redlining, that picked up where covenants left off.

Gordon found that covenants in St. Louis were primarily used between 1910 and 1950 to keep Black residents from moving beyond the borders of a thriving Black neighborhood called the Ville.

In the surrounding neighborhoods north of Delmar Boulevard — a racial dividing line that bisects the city — the St. Louis Real Estate Exchange frantically urged white homeowners to adopt a patchwork of racially restrictive covenants or risk degrading the "character of the neighborhood." The covenants eventually blanketed most of the homes surrounding the Ville, including the former home of rock 'n' roll pioneer Chuck Berry. Most of the homes with racially restrictive covenants in north St. Louis are now crumbling vacant buildings or lots.

"Protected for Particular People"

California was at the forefront of the strategy to use restrictive covenants to keep neighborhoods white. In the Bay Area, real estate developer Duncan McDuffie was one of the first to create a high-end community in Berkeley and restrict residency by race, according to Gene Slater, an affordable-housing expert who works with cities and states on housing policies.

In San Diego, at the turn of the 20th century, the city began to see many of its neighborhoods grow with racial bias and discrimination that wasn't just blatant — it was formalized in writing.

This desire for exclusivity and separation embraced the notion that discrimination was an asset, a virtue that made certain communities desirable. A 1910 brochure, printed on delicate, robin's egg blue paper, advertised a neighborhood, then named Inspiration Heights, this way: "Planned and Protected for Particular People. For those who Want the Best."

Today, the neighborhood is known as Mission Hills. The gently curving roads and stately trees persist, as does the cachet: Homes there today sell for millions of dollars.

Another brochure promised that deed restrictions "mean Permanent Values in Kensington Heights." Yet another touted San Diego as the "Only White Spot on the Pacific Coast."

"For the developers, race-restrictive covenants, they were kind of a fashion," said Andrew Wiese, a history professor at San Diego State University. "In a way that gates were a fashion, or maybe are still a fashion, or other kinds of amenities were a sales fad."

He said white builders and buyers deemed segregation and white supremacy as trendy. Once it was in vogue, people put it in their deeds and assumed that that's what their white buyers wanted. The repetitive language of these deeds, which seems nearly identical from one deed to the next, suggests that racial restrictions were boilerplate clauses.

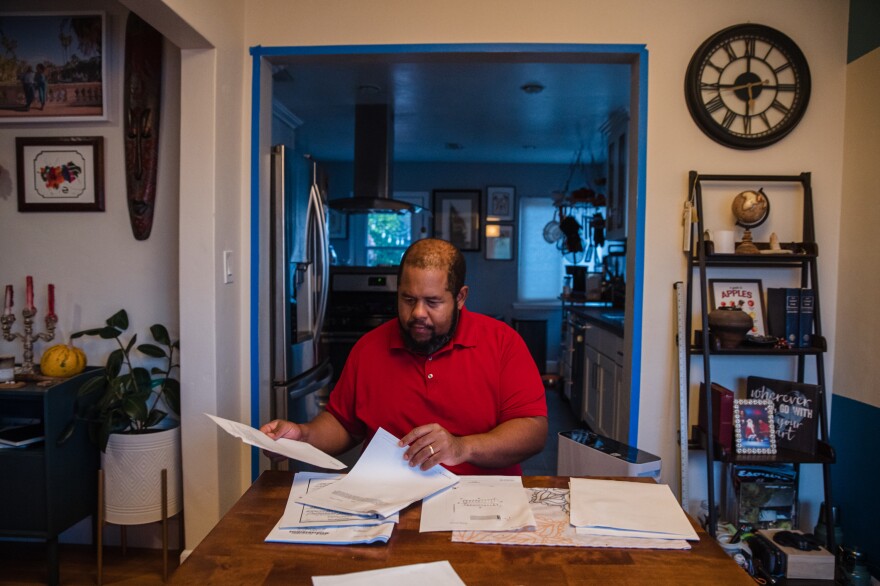

Michael Dew still remembers the day in 2014 when he purchased his first home — a newly renovated ranch-style house with an ample backyard in San Diego's El Cerrito neighborhood, just blocks from San Diego State University.

It took years of scrimping and saving, but the then-35-year-old finally had accomplished what his mother had wanted for him.

"My mother always felt that homeownership is the No. 1 thing that I should pursue in my life outside of my college degree," said Dew, a third-generation San Diegan. "It's a roof over your head. It's an established home."

Dew's house is just a few blocks away from his paternal grandfather's house in Oak Park, the "Big House," where he often visited as a child. A few years ago, Dew decided to look at that home's 1950 deed and found a "nice paragraph that tells me I didn't belong."

"That neither said lots or portions thereof or interest therein shall ever be leased, sold, devised, conveyed to or inherited or be otherwise acquired by or become property of any person other than of the Caucasian Race."

"I've been fully aware of Black history in America," said Dew, who is Black. "I wasn't surprised it was there, but it's just upsetting that it was in San Diego County."

There's no way to determine the exact number of properties that had these restrictions, but no part of the county was exempt. Our examination found restrictive covenants from Imperial Beach, a mile or so north of the U.S.-Mexico border, to Vista, about 50 miles north. Since they were attached to deeds, these restrictions could impact many kinds of real estate, from single-family homes to broad swaths of land that would later be developed.

A review of San Diego County's digitized property records found more than 10,000 transactions with race-based exclusions between 1931 and 1969. The majority of those were recorded in the 1930s and 1940s, but many others went into effect in the decades before, when San Diego's population swelled, and are still on the books today.

An uphill battle

Amending or removing racially restrictive covenants is a conversation that is unfolding across the country.

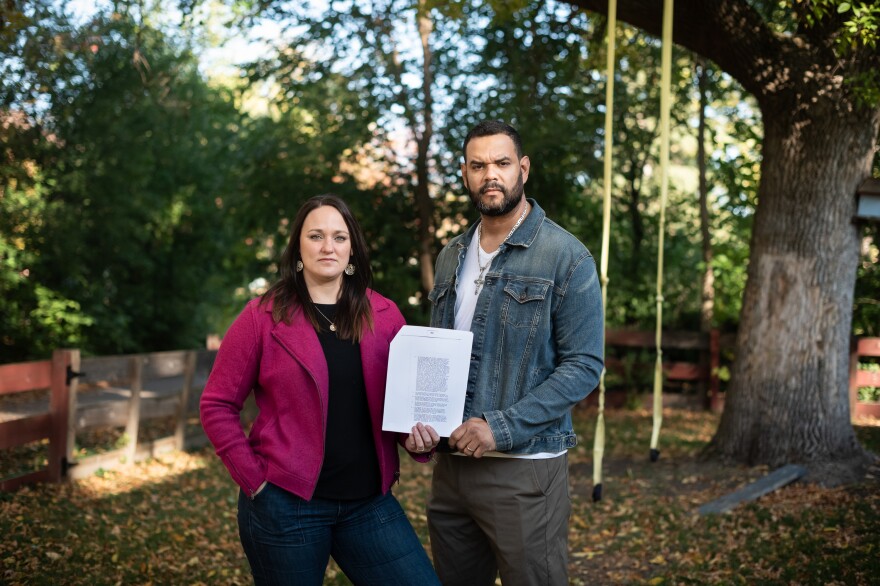

Nicole Sullivan and her husband decided to move back to Illinois from Tucson, Ariz., and purchased a house in Mundelein, a onetime weekend resort town for Chicagoans about 40 miles northwest of the city.

After closing, they decided to install a dog run and contacted the homeowners association. She was surprised when it told her that the land covenant prohibited erecting a fence. The covenant also prohibited the selling, transferring or leasing of her property to "persons of the African or Negro, Japanese, Chinese, Jewish or Hebrew races, or their descendants." The house could not be occupied by those minority groups unless they were servants.

"It made me feel sick about it," said Sullivan, who is white and the mother of four.

She was so upset that she joined the homeowners association in 2014 in hopes of eliminating the discriminatory language from the deeds that she had to administer.

"We were told by the [homeowners association] lawyers that we couldn't block out those words but send as is," she recalled. "Yes, it's illegal and it's unenforceable, but ... you're still recycling this garbage into the universe."

Sullivan knew the only way to rid the language from the record was to lobby elected officials. She teamed up with a neighbor, and together they convinced Illinois Democratic state Rep. Daniel Didech to sponsor a bill. The lawmaker found an ally in Democratic state Sen. Adriane Johnson. The bill allows property owners and homeowners associations to remove the offensive and unlawful language from covenants for no more than $10 through their recorder of deeds office and in 30 days or less, Johnson said. Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker, a Democrat, signed the bill into law in July. It takes effect in January 2022.

"I just felt like striking discriminatory provisions from our records would show we are committed to undoing the historical harms done to Black and brown communities," Johnson said in an interview with NPR. "For far too long, we've been dealing with this."

Johnson, who is Black and lived in Chicago as a child but later moved to the suburbs, said she didn't know racial covenants existed before co-sponsoring the legislation.

Illinois becomes the latest state to enact a law to remove or amend racially restrictive covenants from property records. Maryland passed a law in 2020 that allows property owners to go to court and have the covenants removed for free. And in September, California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, signed a bill that streamlines the process to remove the language. Several other states, including Connecticut and Virginia, have similar laws.

In Marin County, Calif., one of the most affluent counties in that state, officials launched a program in July that aims to help residents learn the history that forbade people of color from purchasing homes in certain neighborhoods, which also prevented them from building wealth like white families in the county did, according to Leelee Thomas, a planning manager with the county's Community Development Agency. The program includes modifying their deeds to rid them of the racist language.

So far, 32 people have requested covenant modifications, and "many" others have inquired, Thomas said. When they learn their deeds have these restrictions, people are "shocked," she said.

"This is an interesting time to be having a conversation about racially restrictive covenants," Thomas said. "With the Black Lives Matter movement, many people in Marin and around the county became more aware of racial disparities."

In Missouri, there's no straightforward path to amending a racial covenant. It takes hiring an attorney like Kalila Jackson, who has done it before.

"If you called a random attorney, many of them probably would say, 'Oh, well, this isn't enforceable. You can just ignore it,' " Jackson said. "But I think we know that's only half the story."

Ending racial covenants was one of the first things on her agenda when she joined the Metropolitan St. Louis Equal Housing and Opportunity Council nearly a decade ago. She's passionate about the work, and her organization provides services pro bono.

In 2016, she helped a small town just north of St. Louis known as Pasadena Hills amend a Board of Trustees indenture from 1928. The residents of what is now a majority-Black town had pushed for decades to remove a provision barring Black and Asian people from living in the neighborhood. Eventually Jackson and city leaders persuaded the trustees to adopt a resolution to strike the racial restriction.

"It was one of those rare moments where you really see truth spoke to power," she said, adding that she hopes Pasadena Hills serves as a model for other towns across the country with such covenants.

Geno Salvati, the mayor at the time, said he got pushback for supporting the effort.

"There are people who are still mad at me about it," said Salvati, who is white. "They didn't want to talk about it. They didn't want to bring up subjects that could be left where they were lying."

Missouri is a state that tried to make it easier to remove restrictive covenants, but failed.

A bill was introduced in the Missouri House of Representatives during the last legislative session that included a small provision to make it easier and free for people to insert a document to officially nullify a racial covenant. The bill stalled in committee.

Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt has spoken out about his commitment to rooting out racist language from homeowners association bylaws across the state over the last year. But he hasn't addressed the hundreds of subdivision and petition covenants on the books in St. Louis.

Schmitt, through a spokesman, declined to be interviewed. He said in a statement that "it would be too premature to promise action before seeing the covenants, but we do encourage people to reach out to our office if they find these covenants."

Jackson, the Missouri attorney, is helping resident Clara Richter amend her property records by adding a document that acknowledges that the racial covenant exists but disavows it. She said it would be easier if the state adopted a broader law similar to one already in place that requires homeowners associations to remove racial covenants from their bylaws.

Without a law or a program that spreads awareness about covenants, or funding for recorders to digitize records, amending covenants will continue to be an arduous process for Missouri homeowners.

"History can be ugly, and we've got to look at the ugliness," said Richter, who is white. "We can't just say, 'Oh, that's horrible.' I feel like it [covenants] should be in a museum, maybe, or in schoolbooks, but not still a legal thing attached to this land."

Cristina Kim is a race and equity reporter for KPBS in San Diego. Natalie Moore covers race and class for WBEZ in Chicago. Roxana Popescu is an investigative reporter at inewsource in San Diego. Corinne Ruff is an economic development reporter for St. Louis Public Radio. The project is part of NPR's collaborative investigative initiative with member stations.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.