Inasmuch as Detroit relied on automobiles, or Pittsburgh on steel, Kansas City once relied on a meatpacking industry that, in turn, depended on a multi-ethnic, low-wage, but organized labor force.

So says social historian John Herron, associate director of the UMKC Honors College. He writes about it in "Wide-Open Town: Kansas City in the Pendergast Era," and traces industrialized meat production here back to 1870, when the first stockyards went up in the West Bottoms.

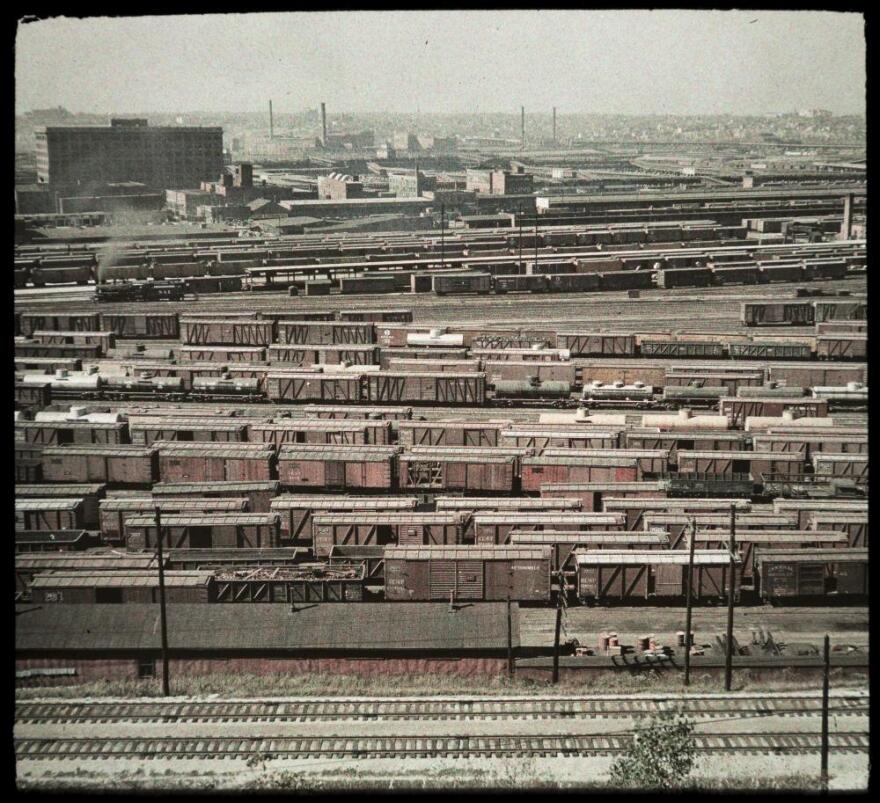

"This was a one industry town, and it was dominated by livestock," he says.

Before long, the number of animals processed in Kansas City was surpassed only by Chicago. By the turn of the 20th century, five million animals per year were being processed near the confluence of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers.

At the time, these factory jobs were sought after by African Americans, who made up about a quarter of the workforce and didn't have many other options. Recent immigrants, too, were attracted to the work. Herron says, "if you look at the roster of employees that work in all the big packing houses, it is like a United Nations."

The steady but meager paycheck meant that "at the same time that African Americans are expanding their foothold in labor politics in the stockyards, they're also building a pretty vibrant culture in Kansas City," he says. "We see jazz clubs, we see sports teams, we see black-owned businesses, protective associations, churches ... all made possible by the infusion of wages paid by the stockyards."

The same was true in immigrant communities, such as Strawberry Hill and Argentine.

The new industry also meant millions in profits for meat packing outfits like Armour, Swift, and Cudahy — companies that live on today as acquisitions and subsidiaries of multi-million-dollar corporations like Smithfield Foods, JBS USA and Bar-S Foods, respectively.

"The stockyards were Kansas City's first million-dollar-a-year industry, first million-dollar-a-month industry, and first million-dollar-a-day industry," says Herron.

Those profits, though, depended on a steady supply of low-wage workers. "There's a very narrow profit margin and you needed to keep your labor costs in check," he says. "So without low-paid wage workers, there is no stockyard industry."

Regardless of their popularity with black and immigrant workers, jobs in the packing houses were brutal and akin to working on an assembly line — repetitive, cramped and fast-paced. The decapitation of cattle, for instance, was supposed to take no longer than eight seconds per animal, says Herron, and a hog should be debristled in no more than two.

"You're also working around knives and saws and cleavers," he says, "and you're doing this in Kansas City, so imagine it's 105 degrees in August."

Workers also had to deal with the institutional racial stereotypes of the day, says Herron, and were largely limited to certain jobs, without much hope for advancement.

"You can read stockyard administrators talking about how troublesome the Italians were and how nasty the Greeks were," he says, "and it was believed that the Japanese and the Chinese were quiet, hard workers, and the Scandinavians were pretty highly regarded."

African American workers, for their part, were largely considered "docile" and, as such, were favored.

"Everybody had a place," says Herron.

Despite the country's racial tension, the poor working conditions and the heat, laborers of different ethnicities banded together and unionized across racial divisions. It's one feature that made Kansas City's labor scene unique, says Herron, who points to strikes in 1904 and 1938 for evidence that African Americans in the stockyards had some standing.

From the union's perspective the first dispute was ultimately a failure, he says, but provided an opportunity for white and black members to unify against the strike-breakers hired in their stead.

The 1938 Armour strike was more successful. It was initiated on behalf of five black hide cellar workers and one Croatian who were protesting an increase in the factory's kill rate, which is exactly what it sounds like. After missing work to file a complaint, their pay was docked. In turn, the entire workforce went on strike and the company relented.

"The grand total was $22 in back pay for these six employees," say Herron, but more importantly "they established the power of these African American workers and the union."

These days, reminders of meat packing's boom days are few and far between. Kansas City's Livestock Exchange building, which was the largest of its kind, still looms over the West Bottoms but is easily overlooked, given the conspicuousness of its wirey white neighbor, HyVee Arena.

Other than that, "you can't really see much evidence of this massive industrial footprint that was in Kansas City," says Herron. That's largely because so much of it was corrals and fences. That history now lives beyond the West Bottoms, he says, in neighborhoods like Argentine and Armourdale, which was created specifically for stockyard workers.

"Even if the physical evidence is gone," Herron says, "certainly the legacy is long and deep."

John Herron spoke with Steve Kraske on a recent episode of KCUR's Up To Date. Listen to their entire conversation here.

Luke X. Martin is associate producer of KCUR's Up To Date. Contact him at luke@kcur.org or on Twietter, @lukexmartin.