For more stories like this one, subscribe to Real Humans on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher or wherever you get podcasts.

The day after Christmas in the year 1900, Carry Nation boarded a train in Medicine Lodge, Kansas, wearing a black alpaca dress and a bonnet. In her hand, she carried an iron rod tied to a wooden cane.

Its purpose and hers were the same: to smash the illegally-operating saloons where men got drunk in plain sight, without consequence, in this supposedly dry state.

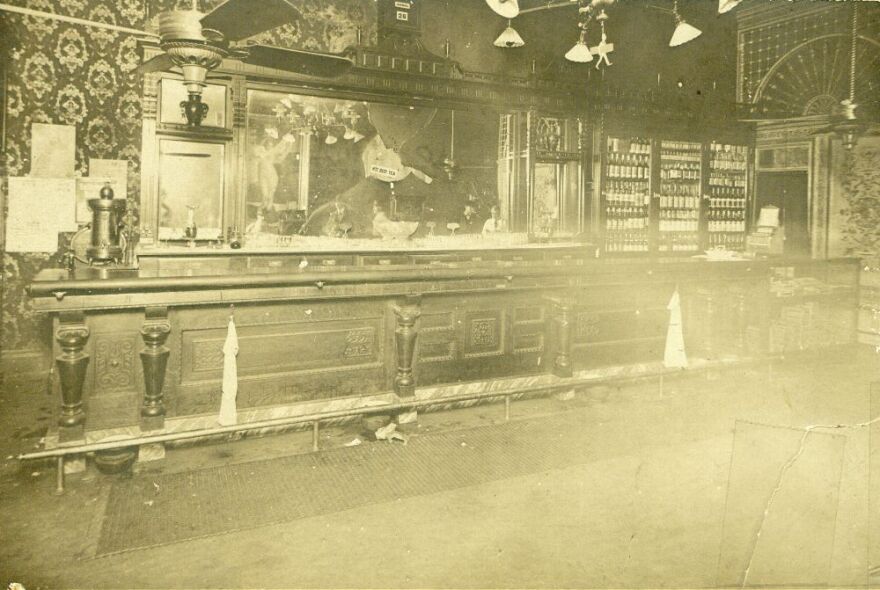

Disembarking in Wichita, Nation checked into a modest hotel, then walked to a bar that had just opened in town. When the young bartender ruefully informed her that he could not serve ladies, Nation picked up a bottle of booze and dropped it at her feet, glass shattering. Then, deeming her cane-rod insufficient for the job, she left — only to return the next morning with a sack full of pointy rocks.

This time, she broke a giant mirror, dented a cherry-wood bar, and punctured a lascivious painting behind the bar. "Peace on Earth and good will toward men," Nation reportedly shouted at the morning-drinking crowd, during one of her many now-infamous saloon-smashing rampages.

I've been thinking about Carry Nation a lot lately.

It's easy to laugh at her dramatic antics, and her story has been told accordingly for generations — with a hearty chuckle. Portrayed as a matronly woman in a bonnet who charged into taverns with a hatchet and a Bible, Nation's popular image is neither flattering nor evidence-based.

Her actions get attributed to everything from menopausal rage to some sort of delusional psychiatric condition. Nation did claim to commune directly with God, something that earned her a reputation as a religious zealot.

But there's a lot more to Nation's story than the popular mythology around her acknowledges. While first researching her years ago, that's something I had a hard time reconciling.

Selling booze was illegal in Kansas, except those responsible for enforcing the law did nothing. And alcohol was hurting people — including Nation herself.

Born Carrie Amelia Moore, she took on the name of her second husband, David Nation. With her first name, she switched the "-ie" to a "y," making her "Carry A. Nation."

But her first husband, Charles Gloyd, had been the love of her life. Shortly after their scandalous elopement in 1867, it became clear that Gloyd was a problem drinker. Financially dependent on someone hobbled by addiction, Carrie nearly starved.

Pregnant and scared, she moved back in with her parents to give birth to her daughter. She was still with them when Charles Gloyd died of pneumonia and delirium tremens in 1869.

For four years, Carrie managed to provide for a child and a mother-in-law all on her own, albeit just barely.

I came to admire Carry Nation's determination, not just to survive her relentlessly grueling circumstances, but to stand up for others even less powerful than she was.

I also saw her as a cautionary tale about giving in, wholeheartedly, to rage. You can be correct in your anger, I reasoned, and simultaneously wrong in how you handle it.

Easy for me to say, I now realize. Unlike at the turn of the 20th century, I qualify for all kinds of jobs, none with policies against hiring women. I can get my own bank account. I can vote out leaders not acting in my best interest — or at least, I can try to. Nation had none of those tools at her disposal.

I first read about Nation a decade ago. Since then, I have sadly acquired more experience feeling powerless watching the leaders and institutions charged with protecting people blatantly fail to do so. I'm not just mad about the needless suffering; I'm heartbroken.

Nation continues to haunt me. Have we misjudged this historic figure? Was she a raving madwoman, or did she handle her outrage strategically, managing to hold sway without any real authority?

Historian Mark Lawrence Schrad thinks it's the latter.

"I see her as a very courageous individual," says Schrad, an associate professor at Villanova University and the author of "Smashing the Liquor Machine: A Global History of Prohibition," a new book about alcohol bans in the United States and beyond.

"She wasn't some sort of holy crone on a broomstick, as she oftentimes gets portrayed, you know, with the overlays of all the misogynist language that kind of comes with that," Schrad told me recently. "She said, 'You wouldn't give me the vote, so I had to use a rock.' So it's fairly straightforward, you know?”

Schrad starts his book with Carry Nation, because he thinks our misunderstanding of her actions are part of a larger misunderstanding of the Prohibition movement.

"The conventional explanations that we have are based more on conspiracy theories than anything else," he says.

Some of this anti-Nation bias, he explains, is sexism — and more specifically, a fear of the Suffrage Movement, which was gaining momentum in Nation's time.

"We associate Suffrage with Prohibition as a way to slime both movements, really," Schrad explains. "Look what they've done to us. Right? We're all freedom-loving Americans who like to drink booze, and then women get to vote."

Even more, Schrad wants us to realize that Nation wasn't actually against "the stuff in the bottle."

"It wasn't about moralizing, and it wasn't about what thou shalt not do. It was a movement against predatory capitalism," he says.

If there's a contemporary parallel, Schrad says, it's the opioid epidemic, the Sackler family and Purdue Pharma.

"Are you okay with Purdue pharmaceuticals going out, getting people hooked on a highly addictive substance, and then just draining them dry and leaving them for dead? If you're OK with that, well, that's on you, I suppose," Schrad says. "But if you're not, if you think that's a problem, congratulations. 100 years ago, you're probably in the temperance ranks.”

We hear more about Nation's "hatchetation" — as she liked to call it — than we hear about the other approaches she tried, with less successful outcomes.

Schrad notes that Nation went into jails to urged wayward inmates toward penitence for their crimes. "She was a jail evangelist," he says. But as she got to know them, she saw them not as sinners or criminals but as victims of societal injustice.

"She asked them, you know, 'Why are you in jail?' They said, 'Well, because of alcohol.' Which was weird because it was a dry state," Schrad says. "So she goes out and says, 'It's not these guys who are criminals, it's the people who are violating the law, who are getting them drunk, who are selling them alcohol in violation of the laws of the state."

What rankled her, again, wasn't people having fun. It was the fact that the people selling booze comfortably enjoyed good standing in their communities, while the people they profited from suffered consequences.

When Nation tried reporting her findings, she found little sympathy.

"She goes first to the bailiff. And then she goes to the judge. And then she goes to the district attorney and then goes all the way up the ranks to the governor to try to get some justice," Schrad says. "Everybody's on the side of the corrupt liquor trade."

One of Schrad's favorite stories is about the time Nation got into a debate with a doctor, who tried to convince her that drinking beer was good for your health.

"She says, oh, OK, great. And she goes over, finds like a case of Schmidt's Malt and starts slamming beer after beer after beer 'til this doctor is horrified that she's gonna get alcohol poisoning," he says. "She's like, 'I have no time for your stupid arguments, I will chug these beers to prove the point.'"

By the time Nation went anywhere with a hatchet, she'd exhausted her options.

"She tried writing petitions. She tried peacefully, picketing. She tried moral suasion," Schrad says. "When all of that fails, what else do you have?"

The thing is: Nation's saloon-wrecking was effective. One of my favorite stories about Nation takes place in the aftermath of one such hatchetation, when a police officer says he wishes he could arrest her.

"You want to take me," Nation responds, "a woman whose heart is breaking to see the ruin of these men, the desolate homes and broken laws, and you, a constable oath-bound to close this man's business, why don't you do your duty?" And a crowd of women start chanting behind her: "Do your duty! Do your duty!"

And you know what? The officer did. He arrested the saloon-operator, whose illegal business shuttered behind him. A lot of saloons shut down after Nation came to town with a hatchet.

Nation also did a lot of charitable work, in addition to loudly calling out corrupt politicians and law enforcement officials. After David Nation filed for divorce, she used the alimony to establish "The Home for Wives and Mothers of Drunkards" in Kansas City, Kansas — essentially a precursor to the modern domestic violence shelter. It was the first of its kind in the state of Kansas.

It's hard for me to admit I'm a Carry Nation stan, because I've absorbed all the cultural shame surrounding her. Her story still leaves me with the cruel understanding that if you take action against an accepted injustice, there's a decent chance that your reward will be a century of mockery.

"That's not on her, though," Schrad tells me. "That's on everybody else. She didn't care."

During a speaking engagement in 1911, Nation collapsed onstage, uttering the memorable last words, "I have done what I could." She was rushed to the hospital, where she died the next day.

Nation was buried beside her parents in Belton, Missouri, near the farm where she spent part of her childhood.

Her tombstone reads: "She hath done what she could."

Maybe it's time to go pay my respects.