For more stories like this one, subscribe to A People's History of Kansas City on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favorite podcast app.

When Barbara Grier was 12 years old, she developed a crush on a girl.

She didn’t know what these feelings meant, but she always relied on books to answer her burning questions. So “the logical thing to do was to go to the library and find out what was going on,” Grier explained in a 1987 interview.

This was during the mid-1940s, when society’s approach to gay people was to ignore them, pretend they didn’t exist, or talk about them in coded language.

As she told it to the Lesbian Herstory Archives, Grier marched up to a library near where she lived in Detroit and asked for books about homosexuality.

“I got on a streetcar, went back home and I told my mother that I thought I was homosexual,” Grier said.

Grier’s mother didn’t know it then, but her self-assured, book-obsessed daughter would go on to become one of the most influential lesbian publishers of the 20th century.

Through the company Naiad Press, Grier fought fiercely for lesbians to see themselves fully represented on the written page — as beautiful, complex, and deeply in love.

“Of course you can have lesbians in books,” Grier said. “What we have done is exactly what we intended to do. Make it not quite as common as Coca-Cola advertisements, but damn near.”

Grier approached her work with a single-minded obsession. And it was in Kansas City that she decided to start her revolution.

‘Yes, you’re a lesbian, and you’re wonderful!’

Grier was born on Nov. 4, 1933, and as a kid, she moved around a lot with her mom and sisters before eventually ending up in Kansas City, Missouri.

“We traveled a lot,” Grier recounted, “so I managed to… fall in love frequently, and out of it, leaving every town in tears, leaving behind the beloved girl of my dreams, and going to a new town, and immediately falling madly in love again.”

Grier always felt comfortable with her sexuality, even when the world around her was not. Her lack of shyness made her an occasional target -- once she was grilled by police for hours after flirting with a woman at a bus stop.

“I was too open in high school,” recounted Grier, who passed away in 2011. “I was so open in high school that probably I could have made my life a little easier in high school if I had been a little less open.

While the media around her peddled “heterosexual conditioning,” Grier’s world was engulfed by queer love, heartbreak and passion. (More than once, Grier seduced and ran away with a librarian she met at the Kansas City Public Library — scandalous!)

Still, Grier was dismayed when she visited libraries and bookstores. There, she found medical texts describing gay people as diseased, overly sexualized lesbian stories written to please men, or book reviews that refused to say the word “lesbian” altogether.

As Stuart Hinds of the Gay and Lesbian Archive of Mid-America explains, things did not end well for gay characters in books at this time.

“If there are multiple characters, at least one of them dies, if not more, and, and nobody ends up happy,” Hinds says. “They're just these melodramas.”

Grier wanted to read books that reflected her own positive experiences as a lesbian.

“Every 16-year-old in the world, when she comes out, should be able to walk into a store somewhere and find a book that tells her, yes, you're a lesbian, and you're wonderful!” Grier told the interviewer.

To that end, Grier began amassing her own personal collection — although the first book she stole from a Kansas City library.

Entering the lesbian literature scene

By the 1950s, Kansas City was the place to be for young gay people — with numerous gay bars that attracted performers from across the Midwest and U.S.

“Kansas City had a big gay community, always did have a big gay community, and it was a safe gay community,” Grier recounted.

Grier was in her early 20s, and she was living in town with her partner at the time, Helen Bennett.

Grier scoffed at the idea that there weren’t as many gay people in the Midwest as on the coasts. “I think there's just as many gay people in Kansas City, as, say, Philadelphia, if you take into account population,” she argued.

In 1957, Grier became a columnist for The Ladder, a lesbian magazine published by an organization called the Daughters of Bilitis.

“The Daughters of Bilitis was the first lesbian advocacy group that was formed in the United States in San Francisco in 1955,” explains Hinds. “It followed on the heels of some other groups that formed earlier in the decade in Los Angeles, the Mattachine Society and ONE Incorporated.”

Obscenity laws and a culture of gay panic — this was also the period of the “Lavender Scare” — made magazines like The Ladder and ONE subversive and, in some cases, dangerous to publish. In some cases, the U.S. Post Office would simply refuse to deliver them.

Another notable magazine included “The Phoenix: Homophile Voices of Kansas City,” the first LGBTQ publication dedicated to exclusively covering the Midwest. But unlike those other publications, The Ladder was entirely devoted to highlighting lesbian culture, defined by lesbians.

“I really do clearly remember realizing, this is what I'm going to do with the rest of my life,” Grier recalls. “This is what I care about.”

“And so, I immediately wrote and volunteered everything. You know, take my soul. You may have whatever you want.”

Grier started writing the column “Lesbiana,” where she reviewed lesbian novels. Grier didn’t go to college, and hadn’t received any kind of formal literary education. But she was determined to become an expert critic, so she read every piece of lesbian literature she could get her hands on.

“I was like the whale's tooth,” Grier said. “I was literally straining the ocean to get every scrap of lesbian material.”

She wrote countless articles for the Ladder — reviews of films, poetry, even pamphlets — under 12 different pseudonyms. For her, these fake bylines weren’t for safety reasons, but because “I thought pseudonyms were romantic.”

You could find Grier writing as Lennox Strong, Vern Niven, Marilyn Barrows, Gladys Casey, and most famously, Gene Damon. “‘Damon’ is simply a variation of the German devil,” Grier explained. “So, I was Gene the devil.”

But the gay rights movement went through a major shift in June 1969, when New York City police raided the Stonewall Inn and ignited a grassroots movement across the United States. The movement, renamed “Gay Liberation,” became more radical.

Tensions developed between Grier and other members of the Daughters of Bilitis, which traditionally took a more reserved and polite approach to advocacy. Grier didn’t want to be constrained.

“ I saw DOB as having reached the point where it was going to melt into a pile of butter,” Girer said. “It was going around and around and around in a tiny, tiny, tiny way. And I was trying to get to a wider horizon.”

So Grier made a bold, albeit controversial move. Along with Rita LaPorte, the new president of the Daughters of Bilitis, Grier stole The Ladder’s national mailing list. And after the magazine folded, it was this list of 4,000 names that helped Grier launch her own venture.

Starting Naiad Press

Grier knew that she wasn’t going to be a writer. She jokingly called her own fiction “ so bad as to be beyond comprehension.”

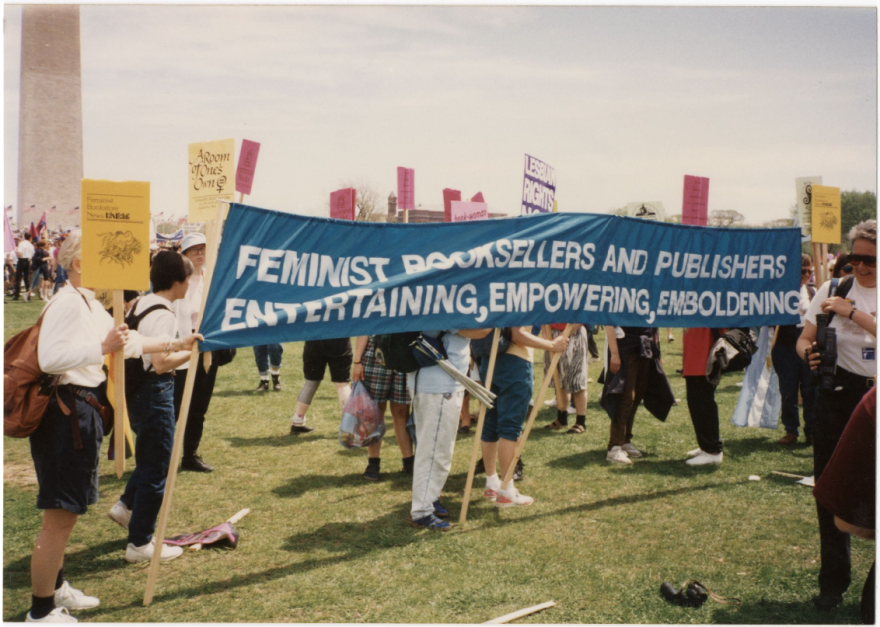

Instead, she saw her superpower as promoting lesbian novels and creating powerful networks of lesbian readers.

“I like being associated with writers that I think are great writers,” Grier said. “I like that power… In a sense, I am looking for my own footnote in history.”

So Grier and her partner, Donna McBride, along with another lesbian couple — Anyda Marchant and Muriel Crawford — started a publishing company. They called it Naiad Press, named after water nymphs in Greek mythology.

In 1974, they published their first book. “The Latecomer” by Anyda Marchant, writing under the pseudonym Sarah Aldridge, was about two women who find themselves sharing a cabin on a ship and fall in love.

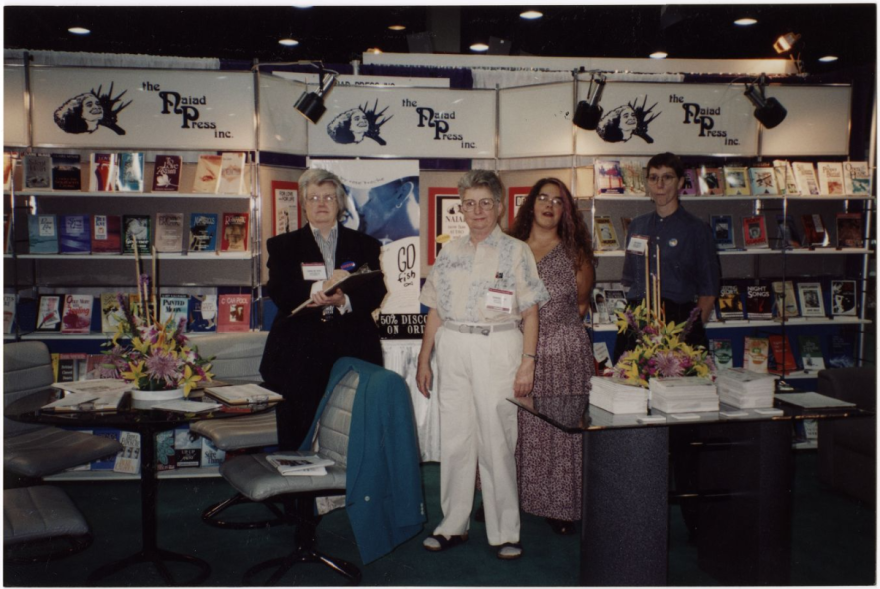

While other lesbian presses were putting out explicitly political books, Naiad focused on positive lesbian fiction. “I think what we're doing is basically making it possible for women to have real access to very affirming literature,” Grier said. “Literature that makes them feel good about themselves.”

Their books told stories about women with undeniable chemistry, who came out at different stages of life and found unexpected connections in settings ranging from the Australian Outback to Reno, Nevada.

Some members of the lesbian feminist movement criticized Naiad Press for what they saw as simplistic and fluffy books. But Grier was adamant that she wasn’t interested in promoting elitist literature.

“Basically we're trying to do books for all levels of readers,” she explained, “and that means you have to have books that can be easily understood.”

It wasn’t easy though. In its early years, Naiad was still not very well known, and definitely not very profitable. Any money made from the publishing of a book went towards the costs of the next one, and they struggled to prove their financial viability as a business.

The press basically survived on loans from Marchant and Crawford, as well as Grier and McBride’s willingness to work for free.

Grier would only take day jobs that gave her access to long distance phone lines, so she could use them to make calls and promote Naiad. She also mailed hundreds of letters to bookstores, magazines, and reviewers to advertise the books however she could.

Controversial publishing decisions

Grier was still running a business, however, and she championed books that she thought would sell.

Her most contentious publishing decision involved the book “Lesbian Nuns, Breaking Silence,” which Naiad published in 1985.

Edited by Rosemary Curb and Nancy Manahan, the book is a collection of 50 personal essays from nuns and ex-nuns about their experiences navigating their sexuality as lesbians in the Catholic Church.

In addition to lining up dozens of TV and radio interviews, and hundreds of articles and reviews, Grier made the highly controversial choice to sell four excerpts of the book to Forum, a porn magazine published by Penthouse.

Members of the feminist community were upset that Grier valued profit over politics by offering these vulnerable stories to publications catering to the male gaze. Contributors felt hurt, because they envisioned their stories being shared with a small circle of lesbian readers, not the sexualized mass market of Forum.

But despite, and maybe even because, of the controversy, the title flew off the shelves.

Grier’s achievements helped position her as a tastemaker and gatekeeper — and she essentially established a lesbian literary canon. But for better and worse, Naiad’s catalog also mirrored Grier’s own tastes, experiences, identities, and her race.

Stephanie Allen, an assistant professor of Gender Studies at Indiana University Bloomington, and the founder and editor-in-chief of BLF Press, a Black Lesbian Feminist press, found that less than 3% of Naiad’s books were by Black authors or featured Black lesbian protagonists.

“That says something to me about the way canons are created, and who gets to decide what literatures are important or should be taught, or should be read and circulated,” Stephanie said. “Often, Black lesbians were not part of that number.”

This problem wasn’t unique to Naiad. It mirrored what was happening in the broader gay rights movement at the time.

Many lesbian organizations centered the experiences and stories of white women, and they weren’t willing to put in the work to address racial inequities in the movement.

Inside Naiad headquarters

As Naiad began making a name for itself, Grier and McBride moved from Kansas City to Florida. Grier could finally quit her day job and become the first paid employee of the publishing company.

“Having been active in the movement for 25 or so years, I finally got paid for something, which was nice,” Grier recounted. “And six months later, Donna quit her job and joined me. And I, being a brave femme with my chin up and a stiff upper lip and all that, cried for a week because I was sure we were going to starve to death because she'd quit her job.”

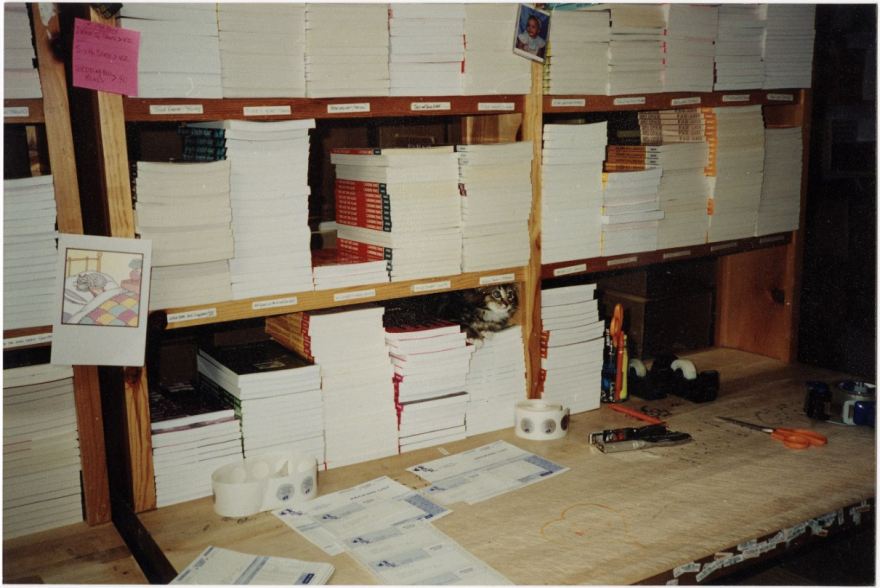

In 1986, they bought the house next to theirs in the woods of Tallahassee, and turned it into the Naiad office. They could finally hire some more full time staff, too.

Michael David Franklin and his team at Florida State University created an oral history project in 2022, where they interviewed people about their experiences being a part of Naiad: “It’s a Lot Like Falling in Love: Legacies of Naiad Press and the Tallahassee Lesbian Community.”

“Oh my God, it was so fun,” said Adrien, who worked at Naiad. “ You know, being in a work environment like that where it was just all us and you weren't ever having to conceal yourself.”

Naiad’s staff would package and send out books and catalogues, working late into the night eating pizza and making queer friends.

“ I just felt so empowered by all of that,” said Alex Jaeger. “Like, no one can touch us… Look what we can do, look what we are doing. Look what we're writing about.”

“It is not just a job, it's a movement,” Grier said of Naiad. “We're doing something, we're changing the world, and what we do is important. And everybody has to believe that. Or they can't work here.”

Barbara Grier’s impact and legacy

By the time Grier and McBride retired, Naiad was a million-dollar business.

When Naiad shut down in 2003, it sold its inventory to a lesbian press called Bella Books, which continues to operate in Tallahassee.

Now, you can find queer sections at many Kansas City bookstores, and at romance bookstores around the country. The Kansas City Public Library hosts a Queer Voices book group, where they read and discuss a different queer novel each month.

Half a century after Naiad Press launched, however, Grier’s mission feels as relevant as ever.

Gay and lesbian novels are being banned in schools and libraries across the country -- and Missouri is especially notorious. Books that even just include queer characters are being labeled as “obscene,” the same language used to censor literature when Grier grew up.

A current U.S. Supreme Court case could allow parents to pull their kids out of classes simply because books with LGBTQ+ content are included in the curriculum.

Grier was, by her own admission, “autocratic and obnoxious” as a leader. But she always remembered where she came from — that 12-year-old girl who sought help at the library — and spent countless hours offering support to lesbians struggling with their identities.

Many women wrote to Naiad asking for advice, and Grier always took the time to respond. “Everybody is paid attention to,” she said. “I really believe in that.”

Grier embodied a fascinating contradiction: She was ready to go to war and obliterate whatever was in her path, but the thing she was fighting for was softness, tenderness, the feeling of being seen and understood.

“ I saw the written word as the tool to change the world,” Grier said. “I still did. Nothing had changed, you see. I was still 16, it was still the books. I was still going to spread the word from coast to coast.”

This episode of A People's History of Kansas City was reported, produced, and mixed by Olivia Hewitt. Editing by Mackenzie Martin, Gabe Rosenberg, and Suzanne Hogan.