Kansas City business owner Chris Goode has watched the stretch of Troost Avenue along 30th Street change since opening up Ruby Jean’s Juicery at the intersection nearly eight years ago.

“When we got here, it was dark,” he said. “It was very little activity. There wasn't a lot going on just even around us, in the immediate vicinity that we can see.”

The area was dotted with empty lots and boarded-up storefronts. Down the block, a dingy muffler shop struggled to stay open and Walt Disney’s old Laugh-O-Gram studio, around the corner, sat crumbling and forgotten.

Now, though, Ruby Jean’s has been a part of stabilizing this block for years. Across the street is The Combine, another Black-owned, local eatery. Operation Breakthrough, an education nonprofit, is just down the street. On the bustling corner at 31st Street are Reconciliation Services and Thelma’s Kitchen, a local nonprofit providing pay-what-you-can meals.

“We got to be pioneers of this resurgence that's happened along Troost Avenue,” Goode said.

But Goode and others worry about the future of Troost, because Missouri lawmakers are now using the historic thoroughfare as a dividing line that splinters Kansas City into separate congressional districts.

The mid-decade redistricting was passed in September during a contentious special session in the Missouri legislature — Republican lawmakers’ attempt to answer the call from President Donald Trump to redraw state congressional maps and shore up a GOP majority in Congress ahead of next year’s midterm elections.

Missouri’s new map places Ruby Jean’s Juicery, on the west side of Troost, in the 4th Congressional District. It places The Combine, on the other side, into the 5th Congressional District. Operation Breakthrough, with buildings on both sides of the street that are connected by a walking bridge, now has a presence in both districts.

“I think that it eliminates what we were after when we erected the bridge over Troost,” Goode said of redistricting. “The people want cohesion and unity and collectivism, but the powers that be want to enact division and want to ensure that division … perpetually maintains itself.”

The General Assembly’s carving up of Kansas City is aimed squarely at U.S. Rep. Emanuel Cleaver II, a Democrat who has represented the 5th District for the last 20 years.

Goode said Cleaver’s impact, particularly east of Troost, can be found at Martin Luther King Jr. Park.

Goode was on the city’s Board of Parks and Recreation Commissioners when Kansas City Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes donated $1 million to build a new playground there, but residents living on the other side of Brush Creek, along Emanuel Cleaver II Boulevard, would have trouble accessing it.

Then, in 2022, the congressman announced $2.8 million in federal funding to build a pedestrian bridge over the creek. Kansas City officials are now asking for public input on different designs for that bridge.

“That's one single example that makes his presence very important for actual people,” Goode said. “Access to abundance, to fitness, to a beautiful park, is something that's just a common necessity for people.”

In recent years, Goode, along with Kansas City Council member Melissa Robinson, has led a coalition aiming to change Troost Avenue — named after a slave-owning Dutch settler — to Truth Avenue, though those efforts are on pause after the legislation stalled last year in city council.

But the redrawing has made Goode feel as if all his work to revive this stretch of Troost doesn’t matter.

“A more diverse audience has been attracted to this historically scary swath of our city,” Goode said about businesses that came to Troost after Ruby Jean’s success. “They followed the risk that I made personally.”

After the redistricting, “that progress seems to be being reversed,” he said.

Missouri’s redistricting is part of a national effort

Redistricting efforts in Missouri are part of a nationwide battle kicked off by Trump earlier this year, when he called on states to redraw their Congressional districts to maintain a Republican majority in Congress.

“The Great State of Missouri is now IN,” Trump wrote on Truth Social in August. “I’m not surprised. It is a great State with fabulous people. I won it, all 3 times, in a landslide. We’re going to win the Midterms in Missouri again, bigger and better than ever before!”

Texas lawmakers passed new congressional maps in August to gain up to five more Republican seats in Congress. Missouri followed in its footsteps, and GOP lawmakers specifically targeted the Kansas City area’s 5th Congressional District with the intention of picking off one of two seats in Congress held by Democrats.

“And that is to push back against the radical agenda that many of the Democrats in D.C. are pushing,” said Missouri state Sen. Brad Hudson, who represents southern Missouri, during last month’s special session.

Missouri Republicans hold a supermajority in the General Assembly, which passed the new maps without a public comment period or alterations. Gov. Mike Kehoe, a Republican, signed the map into law at the end of September. He said the map better reflects the state’s conservative values.

“That will put us in a position where we are sending folks to represent us in Washington, D.C., that will do what Missourians want them to do,” said Hudson.

Under the new maps, Troost Avenue is the primary dividing line separating the 4th and 5th congressional districts. The 5th District takes majority Black neighborhoods east of Troost and groups them with whiter, more rural areas stretching to middle Missouri. The 4th District now includes all of Kansas City west of Troost Avenue to the Kansas state line, and stretches 150 miles south to Dade County.

Several lawsuits challenging Missouri’s new maps are moving through the legal system. Political groups that oppose the redistricting are gathering signatures ahead of a December deadline to put the map up for a statewide vote.

Kansas City’s racial dividing line

Troost Avenue has a long history of racial division in Kansas City. Racist real estate practices like redlining and blockbusting turned Troost into a de facto line of segregation starting in the 1920s, with Black residents living east of the street, and white, more affluent residents living to the west.

“I would explain the history of Troost as going into a small country town and seeing the railroad tracks and understanding that a certain group — specifically the African American community — lives on one side of the railroad tracks and the majority community lives on the other side,” said the Rev. Dr. Rodney Williams, of Swope Parkway United Christian Church.

“The side in which the African American community is not living on, is the side of the privileged and the side of the elite.”

Remnants of that historic divide still impact people today. Poverty levels and crime rates are higher in neighborhoods east of Troost. Residents often deal with blight and vacant blocks more frequently than people living west of Troost. Resources and government funding more often flows west of Troost than east.

“I think it's a stigma that tells them that we don't want you on this side, stay on your side of town, and we'll stay on ours,” Williams said. “I think it is a clear signal of segregation, isolation and alienation that has a psychological impact upon the African American community in Kansas City.”

Troost Avenue was named after Benoist Troost, a Dutch settler who enslaved six people. Troost was the first resident physician in Kansas City and one of its trustees when the city was incorporated in 1850, according to the Missouri Valley Special Collections. The area around where Troost is today was once part of the Porter Plantation, where 40 to 100 people were enslaved.

“Troost is a serious dividing line, racially, in this city,” said Dr. Carmaletta Williams, executive director of the Black Archives of Mid-America in Kansas City, a nonprofit research center and museum studying African American history.

“It's a place that used to house enslaved people — people owned people along Troost,” she said. “That still resonates in the way that we look at Troost and we think about Troost.”

The Rev. Williams said he thinks lawmakers using Troost Avenue as a dividing line in 2025 was an intentional choice. He said Missouri’s redistricting is a blatant example of gerrymandering.

“I think that the decisions that the lawmakers have made is a slap in the face of the Black community, because everybody knows the history of Troost as the dividing line, and we don't like it,” he said.

St. James United Methodist Church senior pastor and doctor of ministry Emanuel Cleaver III — Congressman Cleaver’s son — said the new 5th District will pit the needs of majority Black neighborhoods against rural communities 200 miles to the east.

“Those dollars and those opportunities that were once brought to Kansas City, especially east of Troost, will have to be divided,” Cleaver III said. “It could open old wounds and become that dividing line again.”

‘Could open old wounds’

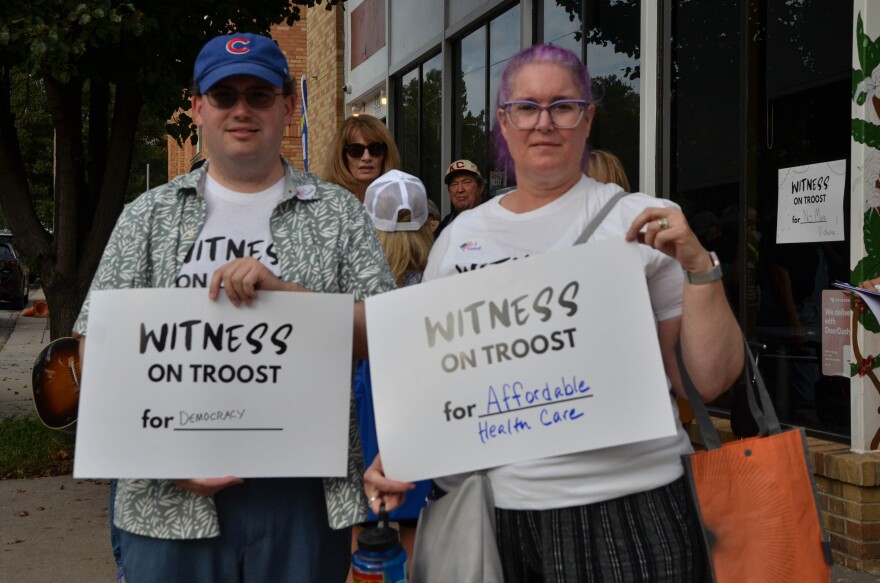

On a Tuesday afternoon in September, a group of a dozen, mostly white Kansas City residents lined up along the sidewalk in front of local coffee shop Equal Minded Cafe, off 44th Street, holding signs that say “Witness Troost.”

It’s part of a new, larger effort to break the stigma of Troost Avenue, and grew out of the Refugees, Immigrants and Migrants Ministry at St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church, further south on Troost Avenue.

Brookside resident Elizabeth Duke, who was part of the afternoon’s action, said the redistricting efforts will disenfranchise people living east of Troost.

“I think a lot of people have been working really, really hard to revitalize this area,” she said. “I drive down Troost all the time and see new things going in all the time and patronize many, many businesses on Troost because they're small businesses and they're local-friendly.”

Sean Kane, a Brookside resident, also attended the Troost rally. The newly drawn districts mean Kane would no longer share a U.S. representative with people living east of Troost. Instead, Kane’s new 4th Congressional District would be represented by Republican Rep. Mark Alford, who has said he plans to run for re-election next year and is confident he can maintain his seat.

But Kane doesn’t think Alford represents his interests or values.

“I will have no representation in Washington anymore, that's the simple truth of it,” Kane said, “because we will have no one in Washington to listen to us.”

A couple miles north, Chris Goode, the owner of Ruby Jean’s, agrees with that assessment.

“My efforts to create collectivism by rebranding this stretch doesn't matter,” he said. “My efforts to bring a very diverse audience around something that's good for every single person that walks through the door doesn't matter. It makes you feel like your efforts are futile.”