This article has been updated to reflect actions taken after publication.

At the start of the year, a proposal to ban cell phones in K-12 Kansas schools seemed to enjoy the same kind of bipartisan support as legislation that brought the Kansas City Chiefs to Kansas and nixed the state sales tax on food.

Republican legislative leaders and Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly put their full support behind a ban. Lawmakers filed bills in the state House and Senate before the session began.

“Smartphones and social media have exposed our children to a world they are not ready for and to social pressures they don't need or deserve,” Kelly said in her annual address to lawmakers in January. “Get that bill to my desk and I will sign it into law.”

But the bill has traced a twisting path through the Legislature. A House committee this week voted to change the policy from a requirement to a recommendation — and then partially reversed that decision the next day, exempting only private schools from the mandate.

“Private schools do not receive our funding and so I don't believe that they should have policy from us,” Republican Rep. Sherri Brantley said in Tuesday’s committee meeting.

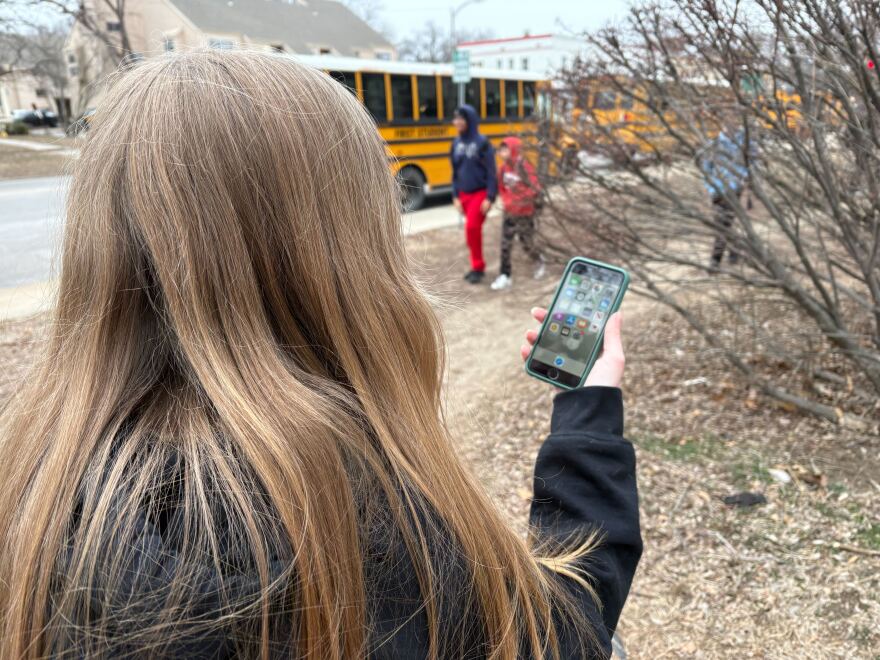

The original proposed ban would have held school districts responsible for keeping students’ phones in an “inaccessible location," like in lockable fabric pouches, for the entire instructional day, with limited exceptions for students with specific medical or learning needs.

Public and accredited private schools would need to start enforcing the ban this fall, at the start of the 2026-27 school year.

The bill would also bar teachers from using social media platforms to interact with students one-on-one, and require school districts to report data on how much screen time students are getting in grades one through four.

Some local school boards have pushed back against the proposed phone ban — as have students and some advocates for private schools, who would also be required to follow the policy under the initial proposal.

Despite widespread agreement in Topeka that students are better off without phones in class, debates over this year’s suggested ban have forced policymakers to consider how much the state should shape the role of technology in young people’s lives.

The case for "bell-to-bell"

A majority of kids aged 12 and under have access to a smart phone — as do 95% of teens aged 13 to 17, according to Pew research.

In 2024, the Kansas State Board of Education convened a task force to study the effects of screen time on students and issue policy recommendations.

In its report, the group cited research linking phone use to addiction, negative social comparison and diminished academic performance. Members issued a list of recommendations including a “bell-to-bell” ban, which involves storing phones away for the entire school day, including passing periods and lunch.

Ava Gustin, a Kansas State University student who co-chaired the screen time task force, told lawmakers recently that she developed an eating disorder in high school — partly because the constant presence of cell phones fueled self-comparison.

“That's something that nobody should ever have to face,” she said.

More than half of states mandate specific restrictions on cell phone use in classrooms. But only two, North Dakota and Rhode Island, appear to have passed laws as restrictive as the Kansas proposal.

Neighboring Missouri passed a bell-to-bell ban last year, though the law is not as strict as Kansas’ bill on how phones should be stored during the day.

Students and staff at one St. Louis-area high school have given the policy mixed reviews, with more socializing but a steep learning curve for teens who have been accustomed to greater phone access.

'Unfairly stripped of my devices'

In testimony, those with concerns about the proposed ban in Kansas have been quick to acknowledge the good intentions behind it — while gently pushing back on policy specifics.

One point of contention is over the scope of the law. Republican state Sen. Renee Erickson, who chairs the education committee, said she does not want the mandate to apply to private schools.

Brittany Jones, who leads the Christian conservative advocacy group Kansas Family Voice, called the private school provision “government overreach.” She said the group would support a cell phone ban if private schools were exempted.

And, perhaps unsurprisingly, some students hate the idea. Kailey Howell from Spring Hill High School testified against the bill in January.

“I’ve learned how to manage my time and put my education first,” she said. “So why am I being unfairly stripped of my devices when I never did anything wrong to earn such a consequence?”

In a February hearing, students from Turner High School in Kansas City, Kansas, said their school’s policy had been successful, despite allowing students to keep cell phones close by.

Turner student Tessa Stoner told lawmakers that some teens who work part-time after school use their phones to stay notified of schedule changes. She also said that keeping devices around could help kids learn how to take responsibility for their own digital habits.

“I have learned that patience and that accountability for my own property,” Stoner said.

Local control

For several of the state lawmakers who initially voted to make the ban a recommendation rather than a mandate, the primary concern came down to two words: local control.

It was a constant theme during legislative hearings on the bill in January and February.

Ann Mah, a former Democratic state lawmaker who spent eight years on the state board of education, said it is not the Legislature’s job to dictate policy for each of Kansas’ varied school districts.

“There's no way you can write one policy that fits (school districts) from fewer than 100 to more than 45,000 kids,” she said.

Representatives from the Kansas Association of School Boards, the Kansas National Education Association, the Kansas Parent Teacher Association and other groups also emphasized local authorities’ desire to maintain control of their policies.

Several skeptics balked at a back-of-the-envolope estimate by state budget officials that, if schools purchased special pouches designed to store phones during the day for each student, it could cost about $13.4 million statewide.

The vast majority of school districts already have policies for cell phone use in class, according to a state board of education survey that 90% of Kansas school districts completed.

Policies varied widely, however, and less than 7% said they required phones to be stored in locked pouches as the initial proposed bill recommended.

Joseph Bishop, an education policy researcher who leads the Center for the Transformation of Schools at UCLA, said he’s hypervigilant about how much time his three children spend in front of screens.

“I'm doing everything in my power for our kids not to have devices,” he said.

But Bishop, who has studied different state policies on school cell phone use, said a one-size-fits-all approach is not ideal.

“Every community is just going to be a little bit different in terms of infrastructure, in terms of capacity of teachers, in terms of student needs,” he said.

Parents, school districts and students all need to take part in the decision making process, Bishop said — not just state lawmakers.

He said the debate isn’t just about the effects of screen time on students, but about how much autonomy to grant kids and teens in shaping their own digital habits.

“This gets into individual rights and who should call the shots,” Bishop said. “There is a struggle right now to figure out a healthy balance.”

Zane Irwin reports on politics, campaigns and elections for the Kansas News Service. You can email him at zaneirwin@kcur.org.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.