St. Louis residents have a deep connection to early professional wrestling that continues today.

The city often serves as a staging ground for the WWE’s biggest events. Last year, fans flocked to the Dome at America’s Center to watch the “Royal Rumble” — which is part of the wrestling company’s “big four” pay-per-view shows. And tapings of “Monday Night Raw” and “Smackdown” often draw thousands of people to the Enterprise Center.

But while it may seem like the WWE always had a foothold in St. Louis, Abraham Josephine Riesman’s book, “Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America,” notes that the mega-company’s place in St. Louis is a relatively new development.

The book, which covers a lot of ground about the wrestling promoter’s rise to power and influence on American culture, also chronicles how St. Louis played a key role in McMahon building his empire.

“Before Vince McMahon decided to become an expansionist with his World Wrestling Federation, wrestling was a regional business,” Riesman said. “It was local.”

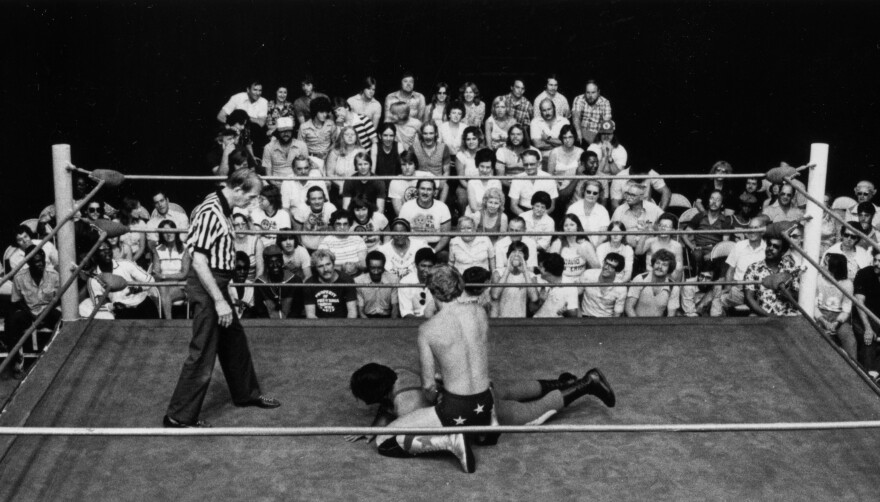

A rich tradition of wrestling

Riesman said there’s a multitude of reasons why professional wrestling took hold in St. Louis, but particularly it was because people loved watching individual wrestlers perform.

“People really like ostentatious performances where human emotions and human problems and human victories are projected into an enormous spectacle. That kind of theatrical storytelling has a lot of power,” Riesman said.

Before the 1980s, the St. Louis Wrestling Club was the dominant wrestling promoter in the region. That company was part of what’s known as the National Wrestling Alliance, a group of regional promoters that effectively dominated the industry for several decades.

The founder of the St. Louis Wrestling Club, Sam Muchnick, was a legendary figure in the history of professional wrestling. Muchnick was also the producer of the popular St. Louis television show “Wrestling at the Chase.”

“Sam Muchnick was a much-beloved and even-tempered promoter of both the St. Louis Wrestling Club and also of the National Wrestling Alliance — which was not a federation. It was a little cartel of promoters,” Riesman said. “But he was the president of that cartel and tremendously influential throughout much of the second half of the 20th century.”

When Muchnick retired in the early 1980s, Riesman said the alliance lost a person who could “turn down the temperature” between competing promoters. And McMahon’s decision to expand his company and the rise of cable television ended up being “extremely disruptive” for local wrestling.

Riesman said McMahon negotiated a deal to have the WWE air on KPLR, which had hosted “Wrestling at the Chase” for years. And after that move, she said the St. Louis Wrestling Club no longer possessed the dominance that it had in their own region.

“And Vince starts doing shows in St. Louis, which was very against the rules,” Riesman said. “And Vince did it over and over again. And the St. Louis Wrestling Club was indeed a casualty of that campaign.”

Which system is better?

The 1980s-era expansion of the WWE did not necessarily mean McMahon had no competition. Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling became widely popular in the 1990s and threatened McMahon’s hold on the company.

But ultimately, WCW folded in the early 2000s, and McMahon ended up purchasing the company. Today, WWE is by far the biggest wrestling company in the world.

Riesman said one of the consequences of McMahon’s consolidation of the wrestling industry is the ability to paint his company in a flattering light. She said that while McMahon would like people to believe that the 1980s era of the WWE was widely beloved, it was actually roundly detested by professional wrestling purists.

“Vince has rewritten wrestling history because he owns wrestling history,” Riesman said. “He owns the tape libraries, and the copyrights for all of the companies that he put out of business that he bought, you know, he has the history of wrestling in the palm of his hands, and he has manipulated it.”

And while Riesman says there were shortcomings in the old system that included the St. Louis Wrestling Club, there were also benefits for individual wrestlers.

“I do think there is a lot to be said for a regional system or at least a system with many players,” Riesman said. “So if for no other reason that it's good for the labor market. Because the wrestlers should have opportunities to go elsewhere and get different treatment.”

‘Thank you for writing about wrestling from a trans perspective’

Riesman’s book has become a New York Times best-seller. As a transgender woman, she said she’s been “very gratified that a lot of wrestling fans have been with me, including a lot of queer and trans wrestling fans.”

She pointed to an instance where a transgender wrestling fan came up to her after a launch event and said, “Thank you for writing about wrestling from a trans perspective, it really means a lot to me.”

“And I really do hope that this helps expand people's conceptions of what a wrestling fan can be and what wrestling can be,” Riesman said.

At the end of their conversation, Rosenbaum asked Riesman what she thought was the big takeaway from her book.

Copyright 2023 St. Louis Public Radio. To see more, visit St. Louis Public Radio.