For more stories like this one, subscribe to Hungry For MO on Apple Podcasts or Spotify.

Before the supermarket aisles, before the ad campaigns, and before the iconic curvy bottle, there was just the Wishbone restaurant in Kansas City.

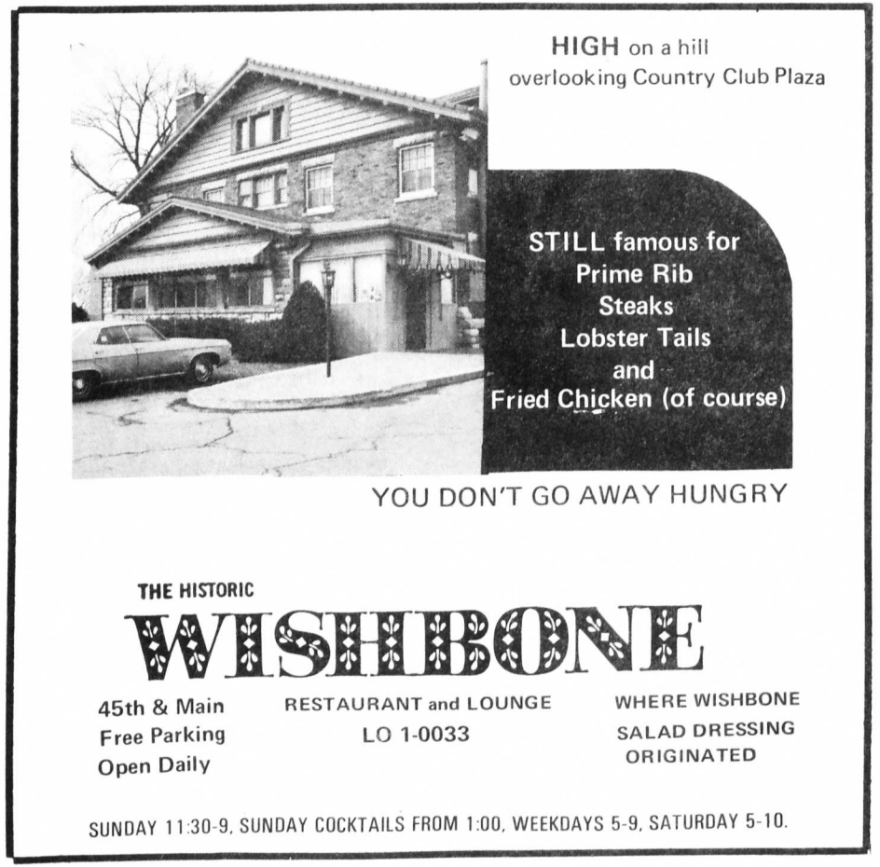

A classy establishment located at 4455 Main Street, the Wishbone served family-style bowls of fried chicken along with prime rib, lobster tails, brook trout, corn fritters, mashed potatoes and gravy — and, of course, salad.

“I used to go to the Wishbone when I was very, very young,” says Jasper Mirabile Jr., owner of Jasper's Italian Restaurant in Kansas City. “That’s where I fell in love with fried chicken.”

Mirabile remembers dining at the Wishbone religiously, every Sunday, with his family. It was a popular place for Italian restaurateurs like his father to socialize.

Opened in 1948, the old Victorian mansion overlooking the Country Club Plaza became equally as famous over the decades for its antique Italian chandelier, neo-Roman style statues, elegant fireplaces, solarium and fine china.

The iconic restaurant is gone now. But if you walk into almost any American grocery store, you'll see its name everywhere, even if you didn't realize it — immortalized in the form of Wish-Bone salad dressing.

“People don't realize about Kansas City and what we have here and what started here,” Mirabile says.

From restaurant tables to grocery shelves

Something important to know about Phillip Sollomi Sr. is that he liked to stay busy. Originally born in Cleveland, Ohio, he found his way to Leavenworth, Kansas, after being drafted to serve in World War II.

“He was a veterinarian, believe it or not,” says Phil Sollomi Jr. “And during the war, somehow he also opened a little restaurant with my grandmother called Brooklyn Spaghetti House.”

Lena Sollomi, an Italian immigrant from Sicily, had previously operated a café in Ohio. After the war ended, the mother-and-son duo moved to Kansas City, Missouri, to start another joint venture: the Wishbone restaurant, in the space of a former cocktail lounge.

Sollomi Jr. said operating the restaurant was a family affair: “My sister and my parents lived on the third floor."

The Wishbone was reportedly a hit right off the bat. But even the popularity of Sollomi’s fried chicken was eclipsed when the restaurant debuted a zesty Italian vinaigrette based on a recipe that Lena Sollomi brought over from Sicily.

The back of the Wish-Bone bottle shows that the dressing includes garlic, onion, red bell pepper and a handful of other seasonings, along with oil, vinegar and sugar. (The Sollomi family still has their original recipe — but of course, they won't disclose what's all in it, only "a little bit of this" and "a pinch of that.")

Patrons started bringing in their own bottles to be filled with the dressing so they could take it home. In 1950, Sollomi began mixing the dressing in a 50-gallon vat and bottling it himself in a converted carriage house behind the restaurant.

By 1952, the salad dressing had become more important to Sollomi than the fried chicken and other food. He sold the Wishbone restaurant to Joe and Dora Adelman — who kept it up for the next two decades — and instead operated Wish-Bone Salad Dressing Co. on Harrison Street.

“When Wish-Bone was first invented, it was sort of a signature salad dressing and people loved to have the bottled form that was the same as they could buy in the restaurant,” says Ken Albala, a food historian at the University of the Pacific. “That's a phenomenon that is uniquely American — that a restaurant could market a product that they have so broadly and make much more money at that than running a restaurant.”

Food companies and restauranteurs had begun commercially bottling and selling salad dressings in the 1910s and 20s. But Wish-Bone is widely thought of as the second mass-produced Italian dressing, right after Ken’s Steak House in 1941.

"Those are really Italian American foods. They're invented here," Albala says. "They're not things that people in Italy would recognize."

According to Albala, Italian salad dressing has a lot in common with products like beefaroni from Chef Boyardee, which was founded by an Italian immigrant in 1928. These products helped marked the start of convenience food, which rose in availability and popularity after World War II, and also appealed to Americans who were just starting to learn about Italian cuisine.

“I think that’s the way Wish-Bone did very well,” says Albala. “They told people, ‘You don’t have to mix salad dressing because you are incompetent in the kitchen and we’ll do it for you.’”

Sollomi initially sold his dressings to grocery stores in Kansas City, Cleveland and St. Louis. In addition to the original Italian flavor, Sollomi Sr. is credited with adding three more salad dressings to the Wish-Bone brand: cheese, French and Russian.

“It was like almost an overnight success. It was very, very popular and it started becoming almost national in scope, certainly regional,” says Phil Sollomi Jr. “But some of the big boys in the salad dressing company didn’t like it. And they were out to kind of squash him.”

At the time, the industry was dominated by larger players like Kraft, who could afford to sell their products at a lower price point if it meant knocking out competition.

When Sollomi Sr. would consult business partners and family about how to take on the competition, everyone told him the same thing: “Lower the price.”

“And my dad, after hearing all this, he looks at ‘em and goes, ‘Nope, we're gonna raise the price,’” says Sollomi Jr. “'We have a great product. We're not gonna sell it for nothing and people are gonna realize it's a great product worth paying for.'”

While other brands sold bottles of salad dressing for 29 cents, Sollomi Sr. ended up charging 39 cents.

"He was just such a visionary on some things," says Sollomi Jr.

Sollomi Sr. wanted to play up his dressing's quality, boasting "just the right touch of garlic" and more herbs and spices than the competition. Right down to the crisscrossed design of the bottle itself, Wish-Bone billed itself as a luxury good.

In a 1977 commercial, the narrator compares the craftsmanship of Wish-Bone Italian to the "care and skill" of cutting a diamond.

"It was all natural," recalls Sollomi Jr. "It was the finest ingredients."

Overwhelmed by a salad dressing empire

Eventually, the business became too big for Sollomi Sr. to handle, so he sold Wish-Bone to tea tycoon Thomas J. Lipton in 1957, for an estimated $3-4 million.

“When they bought it, I mean, our company was a fairly sizable company,” says Sollomi Jr. “The Sollomi way, the Italian way, is you just worked and you put your nose down.”

Sollomi Sr. is remembered as someone who was hardworking and tough, but who also treated employees like family. Former Wish-Bone workers told the Kansas City Star in 1996 that he "never sat still" and “always had a cigar in his mouth."

Phillip Sollomi III remembers how his grandfather always wore suits and had a look in his eye that dared people to mess with him: "He was 5'1" but I remember him as 7'."

At first, as a condition of the sale, Sollomi Sr. stayed on at Lipton as an executive, sitting in on board meetings in New York City. But he hated the idea of working for a corporation and traveling so much — plus, Sollomi Jr. says, his dad was "scared to death" of planes.

“He wasn’t into the hierarchy and the strategy and all that kind of stuff,” says Sollomi Jr. “So after a year, he resigned.”

For 65 years, the dressing continued to be produced in the Kansas City area, at a factory in Independence built in 1961. By the time parent company Unilever sold the brand to Pinnacle Foods in 2013, the salad dressing plant employed nearly 200 people. (Pinnacle Foods and the Wish-Bone brand were acquired by the giant food conglomerate Conagra in 2018.)

Today, Wish-Bone still claims to be America’s number-one Italian dressing, and around the Midwest, it remains the key ingredient for meat marinades, pasta salads, potato salads and more.

But taste buds have changed since Sollomi Sr.'s time. American consumers have gravitated away from bottled vinaigrettes and towards creamy, mayonnaise- or buttermilk-based dressings.

A 2017 survey from the Association for Dressings and Sauces found that Italian dressing no longer holds the title of the most popular salad dressing in the U.S.

The new champion? Ranch.

"You know, someone once quipped that ranch dressing in the Midwest is a beverage," Albala says, laughing.

While Wish-Bone now offers seven varieties of Italian dressing, it's got nine different versions of ranch — from chipotle to light parmesan peppercorn.

Revisiting a legacy

After selling Wish-Bone to Lipton, Phillip Sollomi Sr. moved his family to Phoenix, Arizona. He mostly left his old company behind, apart from keeping a bottle of Wish-Bone Italian dressing in the family fridge at all times.

Sollomi Sr.'s original plan was to retire in Arizona, but, according to his son, that idea got scrapped after a month: “He was bored out of his brain.”

Instead, Sollomi Sr. opened more restaurants. There was the Arizona Ranch House Inn (which served a familiar pairing of fried chicken and Italian dressing) and an Italian deli, co-run by Sollomi Jr.

Sollomi Sr. did eventually retire, and both he and his son forgot about the restaurant industry — apart from occasional anecdotes that would come out when nostalgia hit.

“Dad was really a modest guy. He didn’t tout that,” says Sollomi Jr. “But we certainly knew about the Wish-Bone story and were proud of it.”

Now, the youngest Phillip Sollomi is hoping to bring his family name back into the conversation.

Sollomi III grew up in Arizona and had no plans to come to Kansas City — until he met his fiancé, Amy, who was from there.

"It was actually during COVID. So, long story short, she ends up going back to Kansas City," he says. "You weren't going anywhere. Everything was shut down. So, we FaceTimed every night. And fell in love."

Sollomi III says the pair traveled back and forth for months before he moved to Kansas City himself in April 2022.

“Now I'm living like down the road from where he started this whole journey,” he says.

In between preparations for his upcoming wedding, Sollomi III is investigating his family history. He's spent time digging into old archival material and asking around for old stories people remember about his grandfather.

"It's just fun to relive some of the experiences of people that interacted with him," says Sollomi III. “The more research we do on the Wishbone, the more questions I have."

And it's not just him. Sollomi Jr. now has a regular excuse to come home to the city he was born in. He has questions about the family legacy, too — but mostly he's just excited to relive old memories.

“It’s really cool to be back. If he had to move somewhere, we’re glad it’s here,” Sollomi Jr. says. “It seems like we just have dad's spirit in this town when we're driving around."

Hungry For MO is a production of KCUR Studios, with support from the Missouri Humanities Council. It’s hosted by Natasha Bailey and Jenny Vergara. This episode was written and produced by Mackenzie Martin with editing from Gabe Rosenberg and Suzanne Hogan. Sound design and mix by Mackenzie Martin with help from intern Zacchary Rodgers. Music this episode from Blue Dot Sessions.