For more stories like this one, subscribe to A People's History of Kansas City on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favorite podcast app.

This is the second of a two-part series about the history of jaywalking laws in Kansas City. Read Part One here.

It was bitterly cold on Valentine’s Day in 2020, as Justin Layton walked along 39th street in Independence, Missouri. Heading to a friend’s house, he arrived at Lee’s Summit Road around 11 p.m., reaching the intersection at the same time as a car.

The light was green, so he crossed the street.

Unfortunately for Layton, the person in the car was Independence Police officer Tanner Philip, and he was on patrol duty.

“You are being detained for jaywalking,” he tells Layton on the dashcam video. Philip claimed the pedestrian signal had indicated Layton shouldn’t cross.

Layton, who is Black, kept walking.

The next dashcam video shows Layton on the ground. Philip, who is white, tased Layton, tackled him, and put him in a chokehold. That’s according to a lawsuit Layton filed in 2022 against the city of Independence and several members of its police department.

Facedown in the snow, Layton apologized: “I’m sorry, I’m sorry. I got kids.”

“Don’t be f---ing stupid then,” Philip responded.

Although his lawsuit was dismissed without prejudice in 2023, Layton maintains he was a victim of “walking while Black.”

Countless stories like Layton’s have come out across the country — where relatively innocuous pedestrian behavior has gotten escalated into racially-charged incidents of police brutality.

Because while jaywalking bans are on the books in many cities, data shows that people of color have been disproportionately affected by them.

A few months after Layton was arrested, another, deadlier incident pushed Kansas City lawmakers to start looking deeper at these laws — making it the first major city in the country to completely repeal its jaywalking ordinance.

When walking became a crime

Ironically, Kansas City is where “jaywalking” as a term first came to life. And it was the first city in the U.S. to criminalize jaywalking, back in 1911.

That original ordinance prohibited pedestrians from crossing anywhere other than regulated crosswalks, and carried a potential fine ranging from $5 to $50.

Historian Peter Norton says Kansas City passed its law in an effort to solve the relatively new, but quickly rising, problem of car-related deaths. However, even then, the restriction wasn’t entirely concerned about pedestrian safety.

“There was a more specific concern about who was gonna be liable in the case of somebody getting injured or killed,” Norton says.

In the 1920s, jaywalking became criminalized across America as more cities adopted a version of Kansas City’s legislation. Automobile lobbyists encouraged the movement — it was in the car industry’s interest to convince Americans that the responsibility to make streets safer was on pedestrians, not the drivers who were killing them.

Over the next century, cities redesigned streets and built neighborhoods that prioritized cars over everyone else: more and wider lanes, faster speed limits, parking spaces and oceans of concrete.

As a result, roads have become less safe, not more. Research shows that pedestrians are now just as likely to be hit within an intersection as they are to be hit outside of one — a reality underlined this past fall, when a 9-year-old Kansas City girl on her way to school was fatally struck by a car in a marked crosswalk.

And with dangerous streets dividing neighborhoods, jaywalking is sometimes the most rational choice a pedestrian can make.

" Jaywalking laws are less about traffic safety and more about enforcing people's movement, which doesn't actually make them safer in the long run,” says Michael Kelley, former policy director for the advocacy group BikeWalkKC.

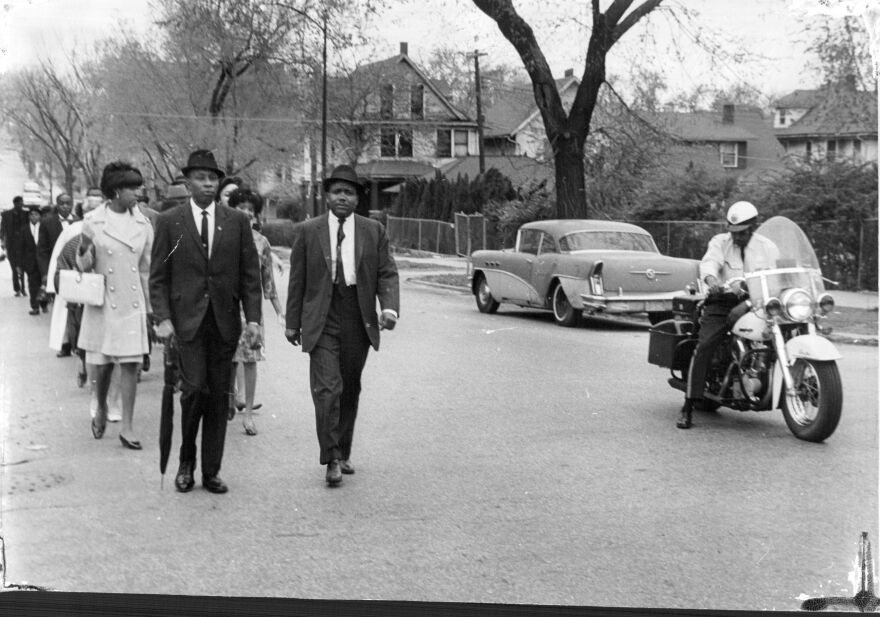

No case better illustrates this than Michael Brown, an 18-year-old Black man who was stopped by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. His offense? Walking in the street with his friend.

Even though Brown was unarmed, and even though they weren’t on a busy road, officer Darren Wilson shot and killed him.

In 2017, a joint investigation by ProPublica and the Florida Times-Union found that Black people in Jacksonville, Florida, were nearly three times as likely as white people to be ticketed for a pedestrian violation.

Your chances increased of being ticketed if you lived in one of the city’s three poorest zip codes, or were a Black male between the ages of 14 to 35.

Similar traffic ordinance investigations in Sacramento, Seattle and New York City have uncovered similar enforcement patterns along racial lines.

When pressed in interviews, the Duval County Sheriff’s Department said the racial discrepancies weren’t the result of an active effort to target Black neighborhoods in Jacksonville.

Rather, the sheriff’s office implied that Black residents were simply violating the law more often than people of other races.

A quiet legislative revolt

Kansas City, Missouri, started to scrutinize its own jaywalking ordinance after the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer in 2020.

Anger over Floyd's death — and long-standing frustrations with police brutality and racism — crescendoed in Kansas City into a summer of protests.

“I walked away from that realizing that if we're serious about trying to make something positive come out of these various tragedies, then it really has to start at the policy level,” Michael Kelley says.

“It can't just be, ‘We'll have a conversation.’ It can't just be, ‘We'll have a moment of silence.’ There has to be something concrete that comes out of something as terrible as what we saw and what prompted so many of us to be in the street in the first place.”

In June 2020, the Kansas City Council passed a resolution instructing city staff to review the full municipal code of ordinances. The idea was to identify instances of racist language or statutes that might cause disproportionate harm against Black and brown residents.

BikeWalkKC decided to do its own deep dive on active transportation laws on the books.

“We essentially asked two questions,” Kelley says. “The first question was, ‘Can this be implemented equitably across the city?’ The second question was, ‘Is this something that's actually going to improve safety for vulnerable road users?’”

BikeWalkKC settled on three laws that it believed created an opportunity for overpolicing of people walking and biking, and that they wanted the Kansas City Council to change.

Sec. 70-268 was about dirty wheels. In essence, anyone with dirty tires on a bicycle (or car) could be ticketed. Sec. 70-706 allowed police officers to make cyclists submit their bicycle for inspection.

Finally, there was Sec. 70-783, regarding “crossing at points other than crosswalks.” Nowhere in the four parts of this city ordinance did it explicitly say “jaywalking,” but that’s exactly what it meant.

Among other things, the ordinance prohibited pedestrians from crossing “at any place except in a marked crosswalk” when traffic controls were in operation. Pedestrians were also forbidden from crossing an intersection “diagonally, unless authorized by official traffic devices.”

“The places that we looked at: Tampa, Minneapolis, New York City. They hadn't done much beyond, say, ‘We know this is a problem,’” Kelley says. “It was really eye-opening and really kind of reinforced for us that this was work that we had to do because we had to take it further than what other folks had taken it to at that point.”

Who got ticketed for jaywalking in Kansas City?

In early 2021, Mayor Quinton Lucas proposed a new city ordinance to amend the city code flagged by BikeWalkKC.

“What really kind of pushed the measure over the top was we were able to work with staff to get data from the city's municipal court,” Kelley recalls.

The Kansas City, Missouri, municipal court data showed a clear pattern. Approximately 123 jaywalking tickets were written by police from 2018-2020. But while Black Kansas Citians make up less than 30% of the city’s population, they were receiving 65% of the jaywalking tickets.

Mostly, Kansas City police tended to ticket Black men. Only 16% of those ticketed were women.

Jaywalking wasn’t the only law where data showed this disparity. Overall, 54% of the pedestrian tickets written from 2018-2020 were to Black individuals, while only 45% were to white individuals.

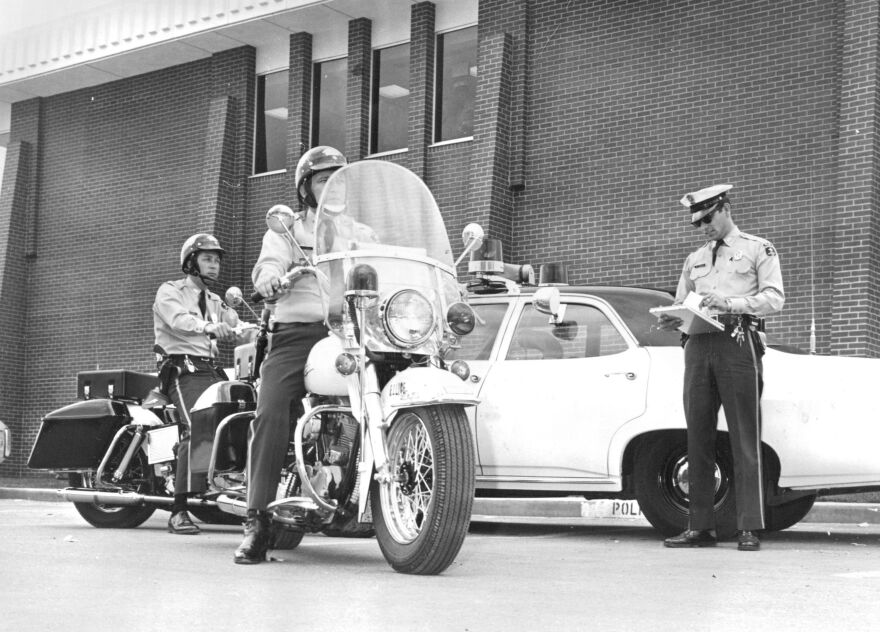

During testimony before the city council, Kansas City Police leaders expressed concerns about eliminating the jaywalking code. They argued that a motorist could be doing nothing wrong and accidentally hit someone who is carelessly walking in traffic. But as city staff pointed out, there were already other pedestrian laws that could apply in that case.

When KCUR asked KCPD to comment on these racial disparities, the department sent this statement: “As with any city ordinance, our officers are charged with enforcing those as they are passed by the city council. If the council adjusts or removes an ordinance, we adjust our enforcement operations accordingly.”

Remember, Kansas City is one of the only cities in the country that does not have local control of its police department. Instead, the KCPD is managed by the state of Missouri.

So even though the Kansas City Council is required to fund the KCPD, its budget and priorities aren’t actually controlled by city leaders. Out of five seats, the only person on the Kansas City Board of Police Commissioners not appointed by the governor is the mayor.

As Lucas’ proposed city code changes worked its way through Council, lawmakers decided they didn't just want to amend the law.

“I think that this is kind of a ridiculous rule. I don’t know if anybody follows it anyway,” Councilman Kevin O'Neill said in a 2021 meeting.

“I think we should go further than this and say that there’s no longer jaywalking as a municipal violation in the city of Kansas City,” said then-Council member Katheryn Shields. “If we look back to what happened in Ferguson, Missouri, I mean, that’s what started that whole thing. Someone walking unlawfully in the street.”

In May 2021, a year after the ensuing protests after George Floyd’s murder — the Kansas City Council voted unanimously to completely repeal the city’s longstanding ordinance banning jaywalking.

“ I think that this puts us really on the leading edge of cities,” said Councilman Eric Bunch, who was a major proponent of the change.

The council also repealed the bicycle inspection law and majorly amended the dirty wheels law.

Setting a trend in the other direction

Four months before Kansas City repealed its jaywalking ban, the Virginia legislature decriminalized jaywalking by moving it to a secondary offense.

But Kansas City technically went even farther than Virginia, because it was the first major city to completely eliminate jaywalking from its code of ordinances.

In order to encourage more municipalities to follow in its footsteps, BikeWalkKC wrote a guide: “Taking on Traffic Laws: A How-To Guide for Decriminalizing Mobility.”

It offers tips for gathering up your local data on jaywalking laws, educating the public about the issue, and forming coalitions with neighborhood organizations and other plugged-in community members to add collective pressure.

Jaywalking is still banned in a lot of states and cities — including many towns in the Kansas City metro. Technically, there is still a state law in Missouri prohibiting jaywalking, but Kelley says it's an area where the state doesn’t preempt city ordinances.

Both Overland Park and Kansas City, Kansas, explicitly prohibit jaywalking by name in its city codes. And since jaywalking is written into Kansas’ uniform traffic code, Kelley says changing that would have to start in Topeka.

Jaywalking laws can be tricky to track down, because — as with Kansas City’s ordinance — many of them never actually use the word “jaywalking” in the text.

For example, Sec. 18.08.004 in Independence, Missouri, states pedestrians can only cross a roadway “at right angles to the curb” or “by the shortest route to the opposite curb” outside of a marked crosswalk. City code like that criminalizes pedestrian behavior even when there isn’t a single vehicle on the road.

Over the last five years, a handful of cities and states have followed the lead of Virginia and Kansas City in rethinking these pedestrian restrictions.

Nevada and California decriminalized jaywalking in June 2021 and October 2022, respectively. Denver and New York City decriminalized jaywalking in January 2023 and October 2024, respectively — and advocates used BikeWalkKC’s guide to inform their process.

“The way I think about it is, in the 20th century, Kansas City was the birthplace for jaywalking as a term and really as a law,” Kelley says. “And in the 21st century, because of our work, Kansas City is now ground zero for decriminalizing jaywalking as both a term and a law, and I think that's pretty cool.”

This episode of A People's History of Kansas City was reported, produced, and mixed by Mackenzie Martin with editing by Suzanne Hogan and Gabe Rosenberg.

Editor's note: KCUR attempted to contact Justin Layton for an interview but did not hear back in time for publication.