In the spring of 1989, Missouri lawmakers were motivated to figure out how climate change would affect the state’s economy, political future and social capital.

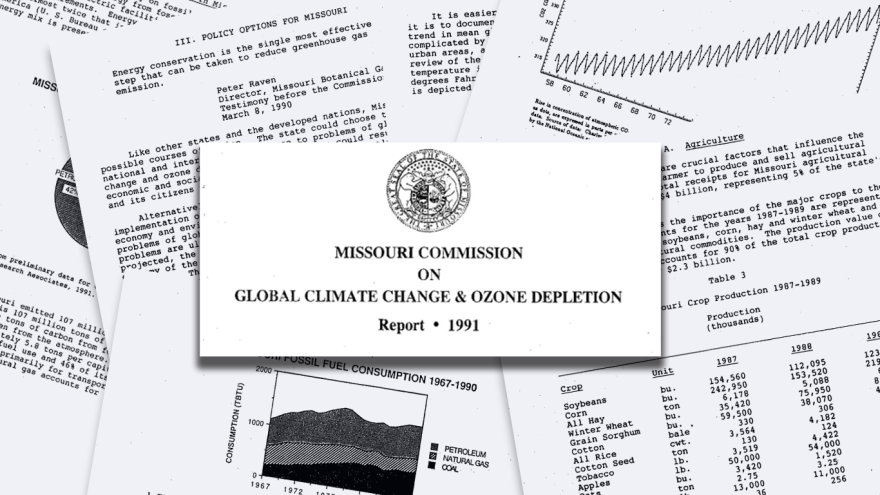

A year after California started looking into climate change, the Missouri General Assembly created a commission of 14 experts and politicians to study the issue and come up with solutions. The result was more than 100 policy suggestions, covering everything from the use of solar and wind energy to transportation and teaching about climate change.

Three decades later, experts say Missouri hasn’t achieved its goals.

‘Such a huge charge’

Commission member John Ward remembers a sense of optimism at the time.

“The commission was given such a huge charge,” said Ward, who back then was a professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City's economics department. “I'd say half of our time is trying to figure out what we're supposed to do.”

They needed to consider global climate change and ozone depletion, which was getting thinner and letting in harmful ultraviolet radiation. (Since then, international efforts have started the recovery of the ozone.)

In 1991, the commission — which included eventual Gov. Jay Nixon — published its report, suggesting things a statewide reforestation program, scholarships for college students studying sustainable agriculture and reducing carbon dioxide emissions by 20% by 2005.

“Our recognition of this situation provides us the opportunity to moderate and to prepare for climate change ... ” the report concluded. “If we fail to be accountable for our role in climate change and ozone depletion, we will pay with diminished quality of life for ourselves and our children.”

Steve Mahfood helped write the report, which he said showed Missouri could be a leader in the U.S. on the issue.

“We normally associate the leadership with the two coasts or Minnesota or other states other than Missouri,” said Mahfood, who later went on to run the state’s Department of Natural Resources. “And this was a very significant step forward in defining what Missouri was going through at the time and what Missouri was going to have to face when it comes to climate change and ozone depletion.”

Missouri created its commission shortly after California — which now is considered a leader environmental policy — created a similar energy commission in 1988. This also all came around the time of the Montreal Protocol, which phased out “the production and consumption of ozone-depleting substances.” The United States ratified it in 1988.

“I think the optimism that we kind of felt was probably somewhat misplaced,” Ward said of the Missouri commission. “I don't know if you can do it again,” Ward said. “I don't know if people would take it seriously.”

That’s not to say there hasn’t been progress in Missouri. Voters passed a requirement in 2008 mandating investor-owned electric utilities get 15% of their energy from renewables by 2021.

But, overall, Mahfood said Missouri is in a “disappointing place.” Consider that since the report was published, Missouri’s carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel consumption have gone up 20%, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Former state Sen. Wayne Goode, who was also on the commission, said the state has “lost a lot of time.”

“Had we jumped into this in the mid-'90s or even late '90s at the turn of the century, and really started doing something,” he said, “we would be so much farther ahead than we are now.”

Cities, activists filling the gap

Missouri’s cities, not its lawmakers, are now taking the lead on climate action. Columbia passed a climate action and adaptation plan earlier this year. And metro Kansas City is working on a climate action plan.

Karen Clawson, the air quality and rideshare program manager with the Mid-America Regional Council in Kansas City, came across the 1991 report while doing research for the plan.

“We're still dealing with some of the same issues and the policies are so relevant,” she said. “There's no reason we shouldn't be pulling a lot of this information out into our current planning work.”

For example, Clawson said the recommendation to find alternative ways to fund transportation and highways on top of the state’s gas tax (which hasn’t been raised since 1996), is something she’s thinking about.

Adaptation now has to be something cities and states planning for moving forward, according to Georgetown Climate Center Executive Director Vicki Arroyo, but she added that it can’t be a substitute for national efforts.

“The states have a really important role, and it's essential, but it's not sufficient,” Arroyo said. “U.S. states have been leaders on this. And they've been able to prove that some of these policies work in that they've been able to reduce emissions while growing their economies.”

The science behind climate change has been around for a long time, said Steve Melton, co-leader of the Kansas City chapter of Citizens’ Climate Lobby. That’s why he’s not surprised Missouri was looking at solutions in the 1990s.

“I've always had faith in my society,” said Melton, whose group focuses on lobbying for climate action at the federal level. “ … I've always believed that reason would win out and that in a democratic society, that if we debated the points that we may not get a right completely or we may not get it right as soon as we should have but that we would eventually get it right and do the responsible thing.

“I certainly have my doubts now.”

Melton’s group wants to see Congress pass a carbon fee and dividend policy, which they hope would incentivize people and businesses to reduce their carbon footprint (Missouri Rep. Emanuel Cleaver is a co-sponsor of the bill).

Young people are taking up the mantle, too, including Sunrise Movement KC. Spokeswoman Queen Wilkes said Missouri’s 1991 report shows that solutions exist — it's just a matter of urgency and action.

“I think that by not addressing this,” she said, “it's a direct attack on this generation’s right to dream this, this generation’s right to decide what they want to do with their lives as they get older.”

Throughout the month of November, KCUR is taking a hard look at how climate change is affecting (or will affect) the Kansas City metro region.

Aviva Okeson-Haberman is the Missouri government and politics reporter at KCUR 89.3. Follow her on Twitter: @avivaokeson.