For more stories like this one, subscribe to A People's History of Kansas City on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or your favorite podcast app.

Fans are already desperately trying to snatch up tickets for the six FIFA World Cup games this summer in Kansas City -- which will be the smallest of 16 cities to host the international competition in 2026.

The city has become an international soccer destination -- with two professional teams of its own, Sporting KC and the Current, a first-of-its-kind women’s stadium, and a recent Premier League fan festival — but that hasn’t come easy.

The quest for professional soccer in the United States was a decades-long struggle filled with failed leagues, gutsy marketing ideas, some poor money management, and diehard fans who saw the sport’s potential.

As it turns out, most of the soccer success that the U.S. is experiencing right now is thanks to a Kansas City businessman who actually got more famous for the other football: Lamar Hunt.

“I think you could make a pretty convincing case that were it not for Lamar Hunt, the World Cup would not be in Kansas City,” says author Michael MacCambridge.

Lamar Hunt's love of soccer

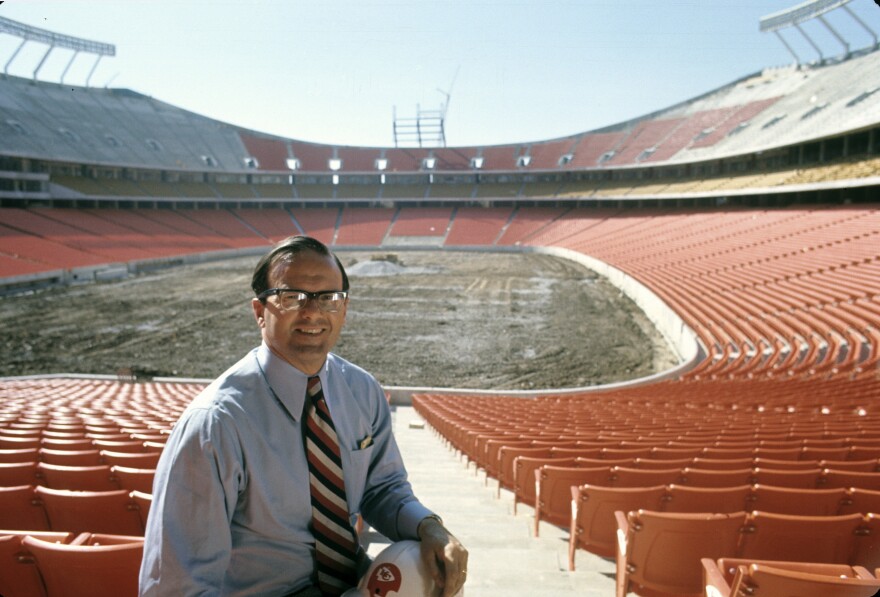

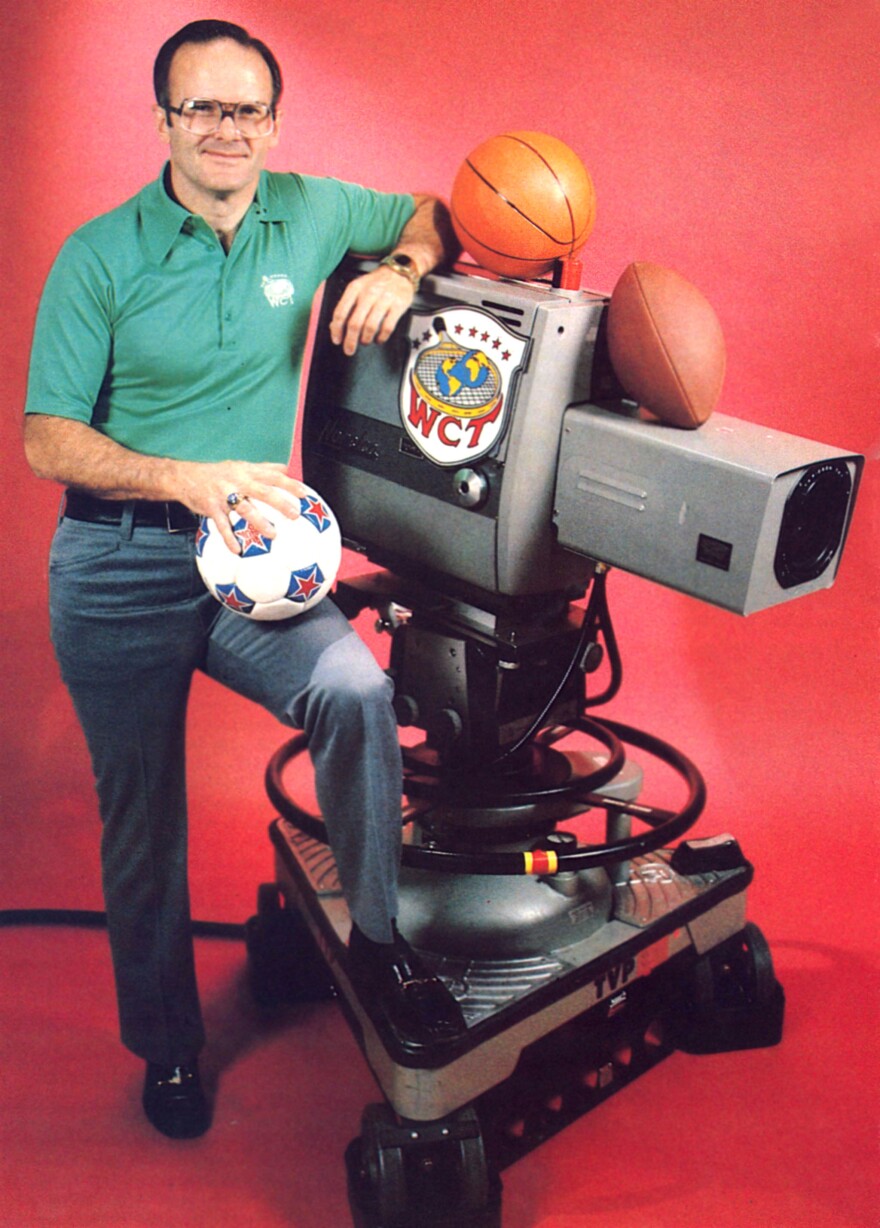

Lamar Hunt is better known for launching the American Football League, bringing the Chiefs to Kansas City, and naming the “Super Bowl.” But he was also a steadfast believer and advocate for the sport of soccer.

Hunt was the son of one of the richest men in the world, a wealthy oil tycoon, and even as a kid he loved competition of all kinds.

“He was one of those nerdy kids who was constantly playing,” says MacCambridge, who wrote the biography, Lamar Hunt: A Life in Sports.

Hunt’s first encounter with soccer was back in 1962, while visiting his future wife Norma in Ireland. On a chilly night, they attended a Shamrock Rovers Game and found themselves in the middle of a standing-room-only crowd.

“He loved the idea of the crowd coming in. And voluntarily having this moment of ecstasy, this moment of jubilation,” MacCambridge says.

A few years later, Hunt watched the 1966 World Cup final between England and West Germany. It was the first time a final was broadcast via satellite, and it attracted over 400 million television viewers.

“After that match Lamar and a lot of other sportsmen felt like, OK, it’s the biggest sport in the world,” MacCambridge says. “The World Cup is the biggest event in the world. The United States is the biggest sports country in the world with all these professional leagues. Surely soccer could succeed over here.”

Scrappy beginnings for an international powerhouse

Up to that point, soccer in the U.S. was mostly seen as an underdog sport of immigrants. Teams and matches were organized by social groups, businesses, athletics clubs and schools associated with those tight knight communities.

There had been efforts to develop national teams and leagues dating back to the late 1800s, but it was a pretty piecemeal effort.

The U.S. played its first international soccer game in 1885, against Canada, but they lost.

In 1904, the Olympics were hosted across the state in St. Louis, Missouri. The U.S. actually had two men’s soccer teams compete, with squads made up of mostly local players, and they won both silver and bronze medals.

The United States Football association formed in 1913, kicking off the U.S. Open Cup.

“And that was a competition that involved teams from all across the U.S., and that was something that kind of galvanized and organized this American soccer identity,” says Phil West, a soccer writer and author of the book, The United States of Soccer. “And it’s a tournament that’s still around today.”

The U.S. qualified for the first ever FIFA World Cup in 1930, and took third place. “There were only 13 teams,” West says. “It was kind of whoever could get to Uruguay by boat, so that was a little bit of a challenge.”

Another notable moment for U.S. soccer happened in 1950, when the U.S. team beat powerhouse England in a World Cup tournament match, dubbed the “Miracle on Grass.”

But after that surprise win, the U.S. men’s team wasn’t good enough to qualify for the World Cup again until 1990 -- four decades later.

As for the women, FIFA wouldn’t even hold a women’s World Cup until 1991 -- which the U.S. won.

The first professional teams in the United States

It’s within these in-between decades that Hunt’s fight for soccer truly took form.

After the 1966 World Cup, Hunt realized that the country didn’t have a strong national soccer program or league of its own. The next year, in 1967, he helped form the United Soccer Association.

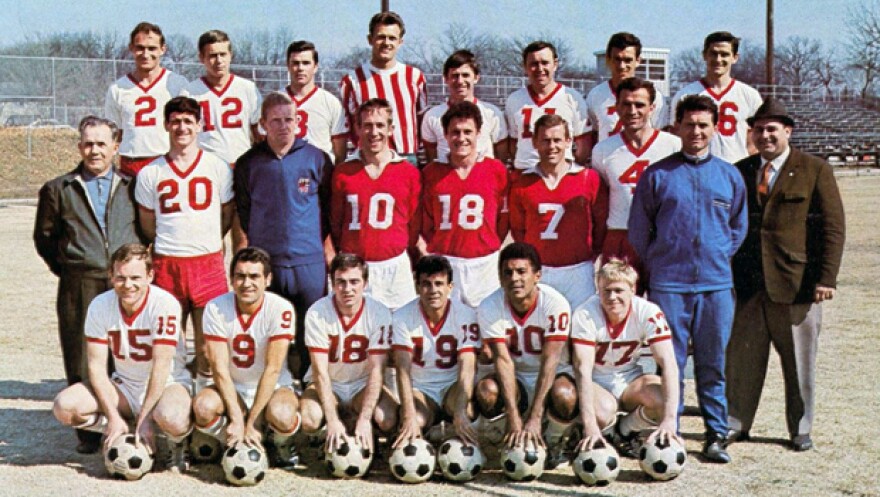

But another nationwide soccer league started at the same time, and managed to land a CBS deal. Worried about competing for attention, Hunt’s association decided to import 12 professional teams from Europe and South America during their off-season, who would then play under the guise of local teams in select U.S. cities.

There was an Italian team that played in Chicago, a Brazilian team in Houston, England’s Wolverhampton Wanderers (AKA the Wolves) played in Los Angeles, and Scotland’s Dundee United played as the Dallas Tornado, owned by Hunt.

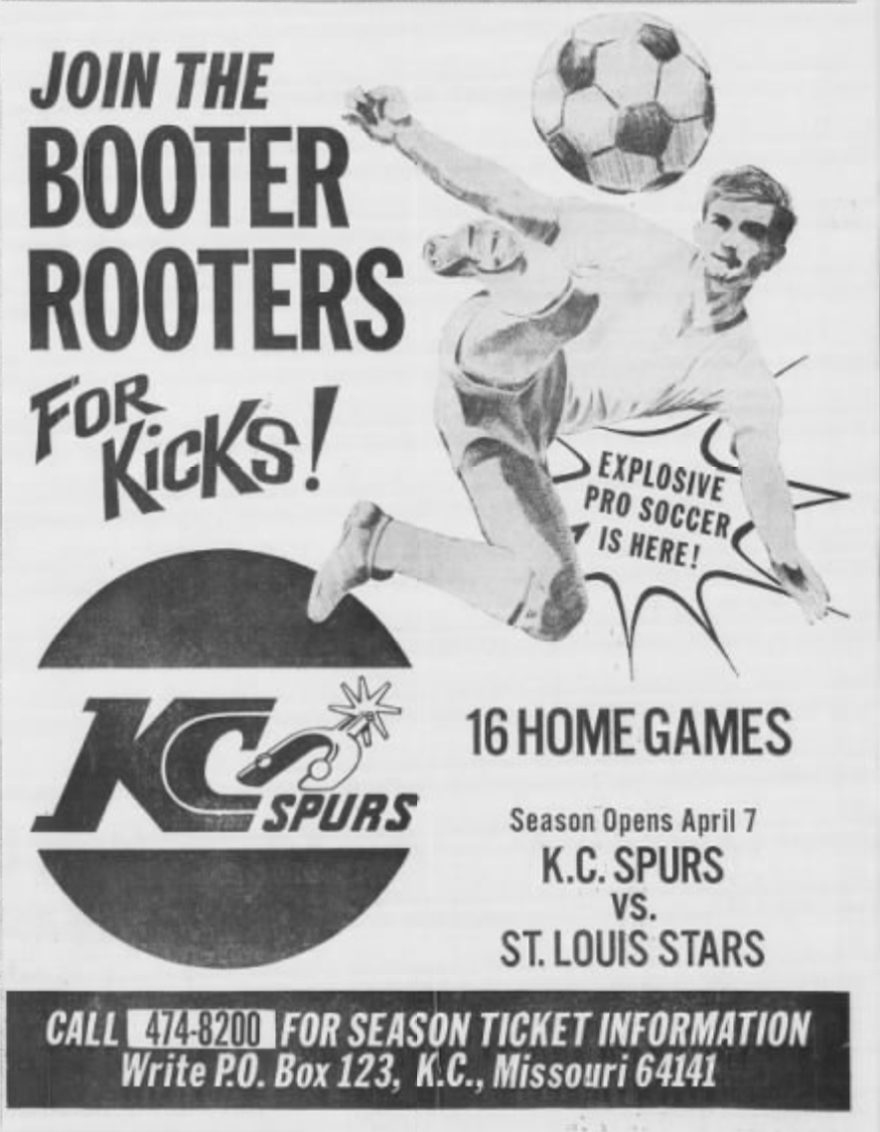

After just a year, the two competing national leagues combined to form the North American Soccer League (NASL.) But the merger left two teams in Chicago, so one of them, the Spurs, were sold to Kansas City.

For Kansas City soccer fans, landing this team in 1968 was a big deal.

“I was just excited that they were having soccer games that my dad could go to, because he was so homesick,” says Yolanda Medina Casey.

Medina Casey is daughter of professional soccer star Chino Medina, a Mexican immigrant and one of Kansas City’s early soccer champions. She was also a Spurette, part of the dance troupe that performed at games.

“Dad went to every game that I performed, not because to see me,” she says, laughing. “But to see a soccer game… just to be in that environment and do your chants, you know that was the fun part.”

Building a fanbase in Kansas City

Unlike the soccer teams that came before, the Spurs got paid. Their early matches were held at Municipal Stadium, where Lamar Hunt’s Chiefs also played.

“We had some fans,” recalls former Spurs general manager John Tyler. “Not many of them, but a good core base. A lot of Hispanics.”

Soccer was still far from the mainstream. The sport wasn’t widely offered in schools, and the national league concept was still so new.

Ticket sales weren’t great, in Kansas City or across the whole league. So organizers did something bold. They invited the most famous soccer star in the world to help spread the word.

Edson Arantes do Nascimento, better known by his nickname Pelé, was a prolific Brazilian goal scorer and served as a sort of ambassador for “the beautiful game.” In the summer of 1968, he traveled to select U.S. cities with his Santos Futebol Clube to play matches against some NASL teams — including the Spurs.

On July 4, 1968, fans packed into Municipal Stadium for the highest attended game in Spurs history. For longtime soccer fans who regarded Pelé as a hero, it was a magical moment.

“I’m pretty sure dad was crying,” recalls Medina Casey. “Because that was huge.”

The Spurettes performed during half time. Santos beat the Spurs 4-1, with Pelé scoring one goal.

“I think we had 19,000 people come to the game to see Pelé, but they never came back,” says manager John Tyler.

Just a year into the North American Soccer League, teams were still losing too much money.

In 1969, the league tried inviting professional clubs from England and Scotland to play as NASL teams for the first part of the season -- thinking that star talent might drum up more attendance.

In Kansas City, this weirdo switcheroo meant the England’s Wolverhampton Wanderers played under the Spurs name for the first nine matches. After they went home, the regular Spurs team played 16 games over the rest of the summer.

And the Spurs played well, beating the Baltimore Bays to become the national champions of the North American Soccer Leagues.

Tyler still has the trophy marking that momentous victory, but he says the reaction from most of the city was “ho-hum.” Even when the Spurs were the best soccer team in the country, it was hard to get enough people to care -- their biggest home game attracted just over 5,000 fans, in a stadium that could hold over 30,000.

Now, both the Kansas City Chiefs and the brand new Kansas City Royals were playing at Municipal Stadium. So the Spurs moved its matches to Pembroke High School -- not exactly championship-level ambiance.

“It’s a credibility issue,” Tyler says. “American people aren’t stupid, and you’re trying to say you’re a major league sport and you're playing in a high school stadium? Please.”

In 1970, after just three years of play, the Kansas City Spurs folded.

‘A sixth or seventh-rate sport’

The North American Soccer League chugged along through the ‘70s, just with fewer teams.

Michael MacCambridge says there was something missing from the NASL.

“The NFL was the best American football league in the world. Major League Baseball was baseball at the very top level. Same thing with the National Basketball Association and the National Hockey League,” he says. “But the North American Soccer League, even at its best, was like a sixth or seventh rate sport.”

Compared to soccer leagues around the world, the NASL didn’t have the same talent pool, money, or fan support. There wasn’t the infrastructure to build up young athletes, or many homegrown stars to look up to. The U.S. national team kept failing to qualify for the World Cup.

“And then you also had basically uneducated American soccer fans,” MacCambridge says.

Most Americans had not been raised with the game, so they didn’t understand the intricacies of soccer and thought it was boring.

The NASL even changed some of the rules to make it more appealing to American audiences, such as adding penalty shoot outs for ties, revamping the offside rule, and making the clock tick down instead of up.

Instead of investing in growing American talent, though, teams kept spending way too much money on foreign players. The New York Cosmos at one point signed Pelé for $1.4 million, a popular move for local fans that created even more imbalance within the league.

“Lamar recognized that the way American soccer was going to grow was eventually with American soccer players, and there was a limit to what you could accomplish just bringing in foreign talent,” says MacCambridge.

By the early 1980s, Lamar Hunt had lost a minimum of $20 million on the Dallas Tornado. In 1984, the NASL and its nine remaining teams threw in the towel.

Planting seeds for the next generation

After the Spurs left, a new kind of soccer craze picked up in Kansas City and around the United States: the Major Indoor Soccer League.

Local fans of a certain generation may recall packed Kansas City Comets games at Kemper Arena. Even though indoor soccer had slightly different rules from outdoor professional games, it helped keep the sport around, at least in some form.

Youth and adult recreational leagues also started gaining more traction in the 1980s.

Spurs general manager John Tyler says one great thing that came from their brief NASL experiment was it created the seed money for the Heart of America Soccer Association, an influential rec league. More opportunities followed, like the Johnson County Soccer League, the Kansas City Legends and the Brookside Soccer Club.

“The concept was correct. If you get kids to play eventually they’ll become fans,” Tyler says. “Grandfathers played and they’re watching their grandsons play now.”

On the American professional market, soccer got another big shot in the 1990s. The U.S. men qualified for the FIFA World Cup for the first time in 40 years.

And Lamar Hunt, along with other businessmen, launched a new campaign: They wanted the U.S. to host the World Cup.

1994 World Cup and Major League Soccer

FIFA awarded the 1994 games to the United States, but with a catch: The country would need to form a professional soccer league, again.

“I think a lot of people felt like, we tried it. It’s just not gonna work in the States,” MacCambridge says.

The opening ceremony of the 1994 FIFA World Cup was held in Chicago (emceed by Oprah Winfrey) and matches were held in arenas across the country. As host, the U.S. national team automatically qualified for the tournament and made it to the round of 16. They lost to Brazil, who eventually won the whole thing.

After the World Cup wrapped up, it took two whole years for business owners to make good on the promise of launching Major League Soccer.

Hunt was brought in to share lessons learned from the NASL, and to plan out how the new league would work.

When the MLS kicked off in 1996, it had 10 teams. Hunt at one point owned three of them: the Dallas Burn, Columbus Crew, and the Kansas City Wiz.

The Wiz were the city’s first professional outdoor team in three decades. But its name was destined to be short-lived.

“I remember asking Lamar once: ‘Lamar, were you aware that Wiz was sort of slang for urination?’ MacCambridge recalls. “And he was like, ‘oh, no, I did not originally know that.”

After lots of jokes, threats of a lawsuit, and a fan contest, the team was renamed a year later to the Kansas City Wizards.

A home suitable for professional soccer

The Wizards played at Arrowhead Stadium, home of the Chiefs. But MLS fans in the U.S. wanted that contagious experience that was a signature part of the game internationally.

It was hard to drum up that same type of energy in a giant football stadium, although Wizards fans tried. First named the Mystics and then later The Cauldron, the supporter group worked with the team to establish a dedicated fan area behind the goal, playing music and leading the crowd in chants.

Hunt soon realized soccer needed a home of its own, on a more appropriate scale. He spent $30 million on the Columbus Crew arena in Ohio. When it opened in 1999, it was the very first professional soccer specific stadium built in the U.S.

“It showed not only American soccer fans, but investors and businessmen the difference — how transformative a soccer specific stadium could be,” says MacCambridge.

Now, nearly every team in the MLS has a dedicated soccer stadium.

“It has made all the difference,” says MacCambridge. “And that doesn’t happen without Lamar. I’m not even sure Major League soccer survives if Lamar doesn’t build that stadium in 1999.”

That same year, the nation’s longest running soccer tournament changed its name to the “Lamar Hunt U.S. Open Cup,” in honor of his lifetime of dedication to the sport.

In time, the MLS created an academy system across the league to develop more homegrown youth talent.

In 2006, Lamar Hunt decided to sell the Kansas City Wizards to another local ownership group. The team underwent a massive rebranding, changing its name to the more European-style moniker of Sporting KC, and built their stadium in Wyandotte County. The cheering section is still named the Cauldron.

Hunt passed away in 2006, at 74 years old. At the time, there were only 13 teams in the MLS, but Hunt had faith that some day it would grow.

Today there are 30 MLS teams, with plans for an expansion. The Hunt Sports Group was a major advocate for the country’s 2026 World Cup bid, and for Kansas City’s unlikely choice as a host city.

His son, Clark Hunt, is now CEO for the Chiefs.

“He was dreaming of this,” Clark Hunt said at a press conference in 2023.

“And in 2026, 60 years after my dad first had that dream, the FIFA World Cup will be played in a stadium he once called his favorite place on earth, GEHA Field at Arrowhead Stadium.”

This episode of A People's History of Kansas City was reported, produced, and mixed by Suzanne Hogan with editing by Mackenzie Martin and Gabe Rosenberg.

This is the second installment of a series leading up to the 2026 World Cup in collaboration with the Great Game Lab at Arizona State University, which explores how sport connects the us to the rest of the world, and the US@250 Initiative at New America.

Read and listen to the first installment, "The immigrants who made us a soccer city," here.

If you know about a local champion of soccer in Kansas City who helped bring the city to this extraordinary moment, email us at peopleshistorykc@kcur.org