For more stories like this one, subscribe to A People's History of Kansas City on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or Stitcher.

January 16, 1975, was a cold day to hold a protest in Kansas City. But it was really only a handful of protesters, anyway, standing in long coats outside the McDonald’s at 2804 Prospect Avenue.

At the boycott, organized by Kansas City's Social Action Committee of 20, picketers held signs with messages like “McDonalds carry big cash out of our community” — complete with a drawing of a stick figure pushing a wagon of overflowing cash.

Protesters threatened to extend the boycott to other McDonald’s locations in Kansas City “if officials of the chain do not change its practice."

Community activist Lee Bohannon said they timed the boycott to coincide around the birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

After all, it was King’s assassination in 1968 that inspired Bohannon to become an activist. It's also part of the reason that Harry Webb, as a Black man, was even given the opportunity to operate that McDonald’s franchise in the first place.

'The day that changed me into the organizer I am today'

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee, on April 4, 1968. His death set off a wave of protests and riots in more than 100 cities across the country — now called the Holy Week Uprising.

Unlike most major cities, Kansas City was relatively quiet for nearly five days. Nothing happened until April 9, 1968 — the day that King’s funeral was nationally televised from Atlanta, Georgia.

On that day, Lee Bohannon was a 23-year-old employee at Tension Envelope Company. After working the graveyard shift, he drove his younger brother to class at Manual High School.

"A block or so from the school, I saw a bunch of kids outside, and I asked them, I said, 'What's going on?'" Bohannon remembers.

That day, the Kansas City, Kansas, school district canceled classes to honor King, but schools in Kansas City, Missouri, had not.

So hundreds of students at Manual High School, Lincoln High School, and Central High School walked out in protest.

“That struck me as an honorable thing for young people to be trying to do,” Bohannon says. “They literally talked me into parking my car and getting out and walking with them.”

The events turned violent though when Kansas City Police, who had been monitoring the situation from the start, sprayed some of the protesters with mace. Elsewhere in town, there were reports of crowds overturning cars and smashing windows.

Despite the upheaval, Kansas City Mayor Ilis Davis agreed to meet protesters at Parade Park. By this point, Bohannon had emerged as a leader in the march.

"By now, I'm enthused and engrossed in this. I'm like, man, you can't stop us from going and honoring Martin Luther King," he says.

At the time, Bohannon told this to the Kansas City Star: “I felt grateful to the mayor... a man of his position, coming out to talk to the kids. But I got the idea that he was trying to keep us here, that he was trying to keep the Negro problems in the Negro part of town... I got the feeling that City Hall wasn’t relevant to us.”

In time, the protesters made it to City Hall. Mayor Davis stood next to Bohannon, who addressed the crowd.

Then, just after noon, violence escalated even further between police and the community. Several days of utter chaos ensued.

In the name of "restoring order," a total of 1,700 National Guard troops and 700 policemen were dispatched in Kansas City. By the time it was all over, six Black people died, nearly 300 people were arrested and city damages totaled around $4 million.

Kansas City’s uprising was one of the largest in the nation that week.

The next day, the Star wrote that Bohannon had “all the accouterments of a young Black militant” — yet it was he who “acted as a link… between city officials and emotionally charged high school students.” In the same article, Bohannon called Kansas City Police, which was 94.5% white at the time — and, as it remains today, under the control of the state of Missouri — “trigger happy” and “gas happy.”

“When Martin Luther King died, almost everybody Black I know had a sentiment that led toward, ‘I’m going to do something for my community. I’m not letting Martin Luther King’s dream die.’ It was like a mantra that started getting in everybody,” Bohannon says. "It was almost like morphing into something."

The day protests broke out in Kansas City was also the day Bohannon met the person pivotal to his future in activism: civil rights organizer Bernard Powell.

The regional director of the Congress of Racial Equality, Powell joined the NAACP when he was just 13 years old. At 18, he participated in the 1964 Selma-to-Montgomery march alongside King.

In the aftermath of the Holy Week Uprising, Powell and Bohannon went on to form the Social Action Committee of 20 in Kansas City. The goal of SAC20 was to connect disparate groups across Kansas City and provide leadership skills to young African Americans.

“Our strength was in the fact that at any point in time, Bernard could say, ‘Hey, I want to get 200 people to come to someplace.’ And everybody just go to they people and we would show up there,” says Bohannon. “That gave a sense of strength that Kansas City had never seen before.”

'Franchising is all about dreams'

1964 was the year the federal Civil Rights Act was signed into law — banning discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. But segregation still remained the de facto rule in many places across the country.

1964 was also the year Harry Webb got his first job at McDonald's. He was a 20-year-old college student at Tennessee State University, a historically Black school in Nashville.

Webb had moved to Chicago for the summer with a simple plan: He’d work, make some money, and then return to college. They started him out at $1.25 per hour.

“I worked there for maybe five or six weeks, and the owner came in and was impressed with my work. And he gave me a 10-cent raise,” says Webb. “I called my mom, I said, ‘Gosh, if they think what I’m doing is good now, I’m gonna break this guy.’”

Sure enough, the owner came to Webb again towards the end of the summer — and offered him a management position.

Webb didn’t want to stay in Chicago, but he had been taught never to say no. So, he hatched a plan: “I won’t tell him that I won’t do it. I’ll tell him something that he’ll reject.”

Webb countered with a salary demand he thought was insanely high: $135 a week. “And he says, ‘You got it.’"

Webb accepted the job — and with it, a seed was planted: “I wanted to become the best Black McDonald’s operator that was in the city.”

McDonald’s was in a period of rapid expansion. Originally started in the 1940s by the McDonald brothers in San Bernardino, California, Ray Kroc took the chain national in 1955 with an aggressive strategy of franchising, which employs local entrepreneurs to run individual locations.

McDonald's now boasts some 38,000 locations internationally, 93% of which are run by franchisees.

“The relationship between franchisor and franchisee is like a distorted parent and child bond, in which the parent sets the rules and the child pays all the household bills," says Marcia Chatelain, author of Franchise, The Golden Arches in Black America.

You didn’t need a fancy business degree to become a franchisee, but you did need access to capital. Today, startup costs for a single McDonald’s franchise will set you back more than $1 million dollars. And franchisees assume a lot of financial liabilities.

A recently published report from the Government Accountability Office found that the franchise system leaves individual location owners without any control over key business decisions — like what suppliers to use and what hours they could stay open, even if it meant operating at a loss.

But if you played your cards right, maybe, just maybe, you could become a millionaire — especially in those early days.

Of course, in the beginning, this opportunity wasn’t available to Black people. That only changed in 1968, after King's death.

“When King was assassinated, it just snowballed,” Webb remembers. “Caucasian operators that were in Black neighborhoods were fearful to come back into the Black neighborhoods.”

As part of the white flight away from city centers, Chatelain says some white McDonald’s franchisees decided to manage suburban stores instead. What remained were damaged restaurants in communities that had suffered a lot of economic losses.

McDonald's billed its decision to hire Black operators as an initiative for inclusivity — but Black operators were also a financial opportunity for the chain.

“This is a test. McDonald's is seeing how they're going to operate after this moment of racial reckoning," Chatelain says. "And it turns out to be quite successful because McDonald's becomes a presence in places where a lot of businesses have left.”

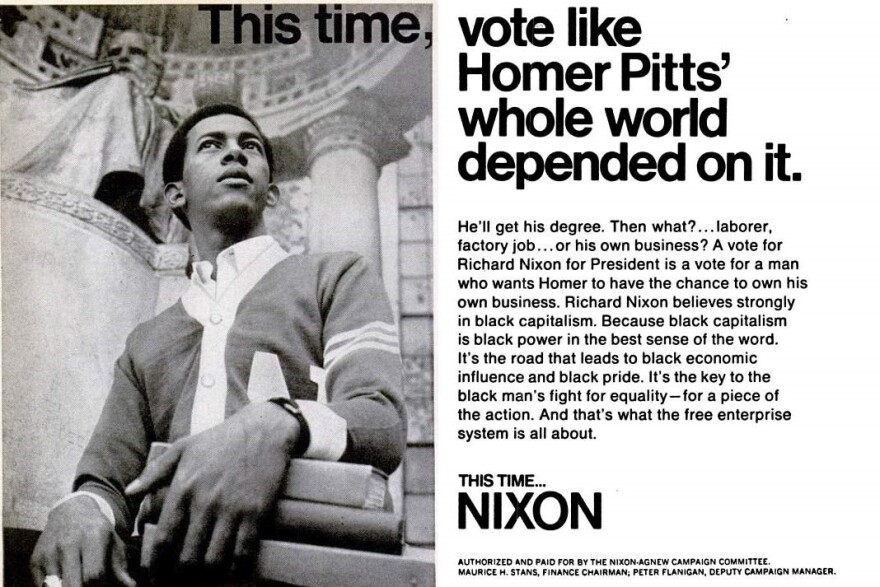

Around this time, Chatelain says the political concept of Black capitalism was seeing a new surge in popularity on both sides of the political aisle.

“Liberals are thinking that owning a Black business, building Black communities is a way of repairing some of the breaches that are caused by racial injustice and economic inequality,” says Chatelain. “I think for people on the right, Black capitalism also helps support segregation, which they weren't really willing to actually do anything about.”

Chatelain says what a lot of Black people wanted was decent housing, good schools, living wages, and for the police to stop beating them. What they got was an influx of federal money and guidance for Black businesses in the form of loans and mentorship programs.

It was a big part of President Richard Nixon's 1968 campaign pitch. That year, only 1% of the nation's private businesses were Black-owned, Time Magazine estimated.

“It creates a system where you have Richard Nixon collaborating with people who would've formally identified as Black radicals. But in this era of real kind of economic desperation, people are willing to make concessions in order to get access to these resources," says Chatelain.

For some Black entrepreneurs, these initiatives from the federal government helped get their foot in the door of a lucrative and growing industry: fast food.

Herman Petty, a barbershop owner, had the honor of being the first Black man to own and operate a McDonald’s franchise. In December 1968, he took over one of the chain's locations on the South Side of Chicago.

But for Harry Webb to realize his own dream of owning a McDonald’s franchise, he had to move from Chicago to Kansas City. And it’s there that his path finally crosses with Lee Bohannon’s — at a picket line.

A united front for Black franchisees

In the beginning, only four cities had Black-operated McDonald's franchises: Chicago, Kansas City, St. Louis, and Milwaukee. In 1972, men from each city became the founding members of the National Black McDonald’s Operators Association, which still exists today.

According to the NBMOA, the national McDonald’s corporation was resistant to recognize it at first. Only 12 operators — including two from Kansas City, Andrew Murrell and Cloris Dale — attended its inaugural conference in Chicago. Other Black franchisees decided not to participate, some worrying that organizing could threaten their ability to expand at McDonald’s.

Nevertheless, the organization grew fast. In July 1975, it held its annual gathering in Kansas City.

"We had started in 1969 with one minority operator... Now, with 1975 drawing to a close, we had 89 minority owners and 116 urban stores," Roland Jones, McDonald’s first Black field consultant, wrote in his autobiography.

“They are really kind of taking a risk by establishing an affinity organization for African American franchise owners. But they do it because they're fully aware of just the challenges of Black business ownership during that time,” says Chatelain. “The National Black McDonald’s Operators Association spent a lot of time really asking questions about how they can be equally represented within the McDonald’s system.”

The Kansas City McDonald's at the center of it all

In 1972, McDonald’s offered Harry Webb his first franchise at 2901 Troost Avenue in Kansas City. He moved from Chicago to accept the job.

"We as minorities often said that we would accept the McDonald's franchise site-unseen because we believed that much in their success," Webb says.

Three years later, Webb took over a second franchise location: 2804 Prospect Avenue, already outfitted in the red-and-white tiles of those classic McDonald's.

In the early 1960s, before it became a McDonald's, 2804 Prospect Avenue was a Safeway supermarket.

Chatelain says this was part of an all-too-familiar pattern during the '60s of grocery stores shuttering in urban neighborhoods and not coming back: "I think that led to what we see now as an expansion of fast food in certain communities."

These days, 2804 Prospect no longer displays the golden arches, but in 1968, it was one of only about 1,000 McDonald’s locations in the country.

It also happened to sit at the cross section of civil rights and business in Kansas City, quite literally.

One block north of the building was the headquarters of SAC20. Three blocks north was the Kansas City chapter of the Black Economic Union. Both groups were formed in 1968, the same year that a three-block section down Prospect Avenue was destroyed during the uprising.

“We looked at it at that time that Black businesses could ride on the wave that we were making,” Bohannon says. “Black businesses aren't the ones that start standing up and shouting at the mayor. But a lot of Black entrepreneurs found themselves the golden opportunities because of that.”

The way Bohannon tells it, the problems at 2804 Prospect began with a community bike race.

SAC20 members were going up and down Prospect, asking for donations from all of the area businesses. Supposedly, Powell asked McDonald’s to contribute to the cause, but he was told no — something to do with a “company policy.”

“So, [Bernard] said, ‘Well, I tell y'all what we going to do,'” recalls Bohannon. “We're going to picket your place and our people are not going shop at your place anymore.”

It's impossible now to verify what happened first-hand — Bernard Powell was killed in 1979, at the age of 32.

At the time, though, Powell told the Star that their boycott would continue pending the outcome of a meeting with a McDonald’s official, and they threatened to extend the boycott to other McDonald’s franchises in Kansas City if the chain didn’t change their practices of “only taking money out of the community.”

Bohannon emphasized that point in a 1975 interview with the Kansas City Star. He called McDonald’s a “one way trade” business, adding that it "always takes in and never produces anything in that community, one which still holds onto the old line that businesses should only deal with City Hall.”

SAC20 wanted McDonald's to contribute to the area's economic development and stability, beyond just hiring Black workers.

“When I purchased the franchise, I guess they saw me as part of corporate world,” Webb remembers. “They wanted to make sure I understood that I wasn't just making profits in the community and taking it out, living in another community and not reinvesting.”

Webb was the new guy on the block — he had just taken over the McDonald's location, he wasn't from Kansas City, and he was only somewhat familiar with SAC20.

Bohannon remembers the protest as being about something much bigger than just this one franchise, though.

“What we were trying to do was to force the national, not only to work with the community, but be better stewards with the owners and the managers that were Black at McDonald's,” says Bohannon. “We took the point that regardless of whether you're a Black entrepreneur or not, that's not gonna keep us from putting pressure on the national organization of McDonald's.”

“The boycotting of McDonald's, by Black members of the Kansas City community, to a Black-franchised McDonald's really illustrates some of the tensions that emerge in the 1970s about whether McDonald's was an authentically Black business,” says Chatelain. “Are they really invested or investing in communities or are they merely just engaged in window dressing?”

Webb says the community was torn about the protest, and thinks the boycott only lasted a week or two.

“A lot of the people that [Bernard] was trying to protect was hurt by it because there were people that lived in the community that was employed by me," he says. "And there were certain things that McDonald's required of me that I couldn't do.”

Eventually, Webb and SAC20 came to an agreement: Webb would donate to various community events that SAC20 and others were putting on. Once they sat down and talked it out, Webb says it was actually pretty congenial.

“I would’ve done it without the protest,” Webb says. “That was one of the reasons why McDonald’s were willing to get Black operators. So that they could come into the Black community and be a part of it… I guess they were just trying to hold my feet to the fire to make sure that I knew.”

‘We had the same goals’

After the boycott, Webb renovated 2804 Prospect, adding a proper dining room. Even Bohannon remembers how it became a pretty popular gathering place for the Santa Fe neighborhood.

Back then, hamburgers were 28 cents and Big Macs were 65 cents.

“We would get a lot of coffee drinkers. It was the perfect restaurant for that,” Webb remembers.

One of the big highlights of Webb’s career was watching the debut of the Happy Meal, the brainchild of acclaimed Kansas City marketer Bob Bernstein in 1977.

Webb also remembers how he gave a lot of teenagers in the neighborhood their first job.

If they didn’t have a bank account, Webb would bring them to his bank and introduce them to the president, so they could open one. "When they got the paycheck, they could walk down to the bank and feel some sense of pride," he says.

Webb was strict about punctuality and dress codes, but he also pushed his employees to do their homework before clocking in. He still gets calls from some of the folks he hired back then.

"It was a lot of encouragement," he says. "I had to wear a lot of hats: employer, father, friend."

2804 Prospect was, in its own ways, a family operation. Webb says his best manager was his brother, Lewis, who went on to become a franchise owner himself.

In her book, Chatelain found that many Black McDonald's franchise owners across the country tried to pick up the slack where society was failing. McDonald’s operators supported Historically Black Colleges and held job fairs and voter registration drives.

"There was always someone in the community that wanted something," Webb says. "Most of the time, when you could, you always said yes."

In the years after the 1968 uprising, SAC20 spearheaded a lot of beautification efforts in Kansas City's most affected corridors — like Prospect.

Before he moved to New Orleans, where he lives now, Webb says he'd join in on things like neighborhood trash pickups.

“SAC20 was good for the area," Webb says. "We all had the same goals: to improve the community."

Chatelain says McDonald’s created a “blueprint” for other fast food restaurants to do similar minority recruitment efforts. But not everyone had as positive an experience as Webb did.

Many Black operators — and employees — have been frustrated with how they’ve been treated. Over the years, lawsuits have claimed that McDonald’s practices its own kind of "redlining."

In 2021, Black operators led a protest at McDonald’s world headquarters in Chicago, hoping to call attention to McDonald’s "discriminatory practices." Protesters alleged McDonald’s put Black operators in economically distressed communities with high levels of crime, leading to higher overhead costs and lower profits.

Webb says there is truth in how much harder Black operators had to work, but it doesn't make him bitter.

"Those same things that were giving us trouble was one of the reasons that some of the other non-Black operators didn't wanna be there," says Webb. "It created an opportunity for us. So we just had to figure out ways to make it work."

“It is not possible to say, well, everything was bad. Because we do see some positive outcomes. But I think a more important question is to ask: At what costs?" asks Chatelain. "At what costs do these types of economic initiatives come at for local communities and for the people who are working within them?"

"All of these ways that McDonald's becomes another actor in this dramatic moment in American history, I wanted people to see that it wasn't just the place, it was a significant part of the story of struggle and the story of solutions and the story of unfinished business of race relations in America," Chatelain says.

Lee Bohannon says that he's come to have a better understanding of these Black franchise owners — and the restrictive rules they had to operate underneath.

"They were Black men at a time when we were struggling for identity and all of that," Bohannon says. “In hindsight, I understand Cloris and them was just trying to make it and trying to get into the major cycle for Black businessmen.”

Bohannon is 78 years old now and still lives in Kansas City. He has about 30 grandchildren, plays a lot of chess and always seems to be wearing a fedora. And somehow, he appears just as fired up about community organizing as he was when he was 23.

"When I see these young people on the City Council in Kansas City start speaking for reparations, and educate the city on the fact that we need to do something about that, I'm fascinated!" Bohannon says. "They didn't pick that stuff up on their own. These are things that has been cultured into them through the work of their ancestors for years to come."

The other thing that Bohannon is jazzed about these days? A community garden he’s working on at 77th and Prospect, which is probably about as far from fast food as you can get.

This episode of A People's History of Kansas City was reported, produced and mixed by Mackenzie Martin with editing by Gabe Rosenberg and Suzanne Hogan.